Educator and Wife of John James Audubon

Lucy Bakewell met Frenchman John James Audubon when he came to America in 1803 to oversee his father’s estate, Mill Grove, next door to Lucy’s family home, Fatland Ford. Audubon was eighteen; Lucy was sixteen, and she might have been jealous of his new passion: American birds. She was educated and physically strong, and she sometimes observed birds in the forest with Audubon.

Image: Lucy Bakewell Audubon in 1831

Early Years

Born January 18, 1787 in England to a wealthy family, Lucy was the daughter of William Bakewell and Lucy Green. The family immigrated to the United States in 1801 and settled on an estate called Fatland Ford near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. John James Audubon spent his childhood largely outdoors in the French countryside. He trained briefly as an artist in Paris and started observing and painting birds. In 1803 Audubon’s father sent him to America to oversee the family plantation, Mill Grove, which adjoined the Bakewell estate.

When Audubon arrived in America there were only six million people here and miles upon miles of wilderness, a paradise for birds. He became completely at home on the frontier, the perfect place to observe. Sometimes he disappeared for months, with little more than a gun and painting supplies.

Lucy Bakewell and the eccentric young Frenchman met and fell in love. She taught him English; he taught her painting, and they went for long walks together in the surrounding forests. Eighteen years old at the time of his arrival, Audobon spent much of his time hunting, observing, collecting, and sketching. During these years, he built a substantial collection of ornithological art, and his skill as an artist increased rapidly.

While at Mill Grove Audubon began making drawings and developed what he called a wire armature, a device that held the birds and other creatures he had just killed in place while he made drawings of them. This unique method put him light years ahead of his contemporaries. Many believe that no one has equaled Audubon’s achievements. He also became proficient at taxidermy. His room was brimming with birds’ eggs, stuffed raccoons and opossums, fish, and snakes.

Marriage and Family

Lucy Bakewell married John James Audubon in 1808 and moved to Louisville, Kentucky as part of the first generation of a great wave of migrants who were moving West across the continent. The couple spent their early years of marriage on the Kentucky frontier where Lucy gave birth to two sons: Victor Gifford (1809) and John Woodhouse (1812).

In partnership with a fellow Frenchman, Audubon opened a series of stores, the first in Louisville and two farther down on the Ohio River. Despite her privileged upbringing, Lucy proved to be a resilient frontier woman, adjusting fairly easily to the rowdiness and toughness of frontier life. She appeared to be happy to dedicate her life to helping him achieve success, realizing all the while that the responsibility of holding the family together would likely fall upon her shoulders.

Financial Ruin

Audubon and some of Lucy’s Bakewell relatives invested in a steam-powered grist mill, the most advanced technology of the time. Lucy’s family reneged on their agreement, and Audubon’s business collapsed in the economic crash of 1819. Authorities jailed Audubon for nonpayment of debt and bankruptcy. They auctioned off the family home and all their possessions. The loss of finances and prestige shattered Audubon emotionally; Lucy was his tower of strength.

Painting America’s Birds

Audubon turned to his artistic talents to support his family, announcing his intention to paint every bird in North America for eventual publication. A self-taught ornithologist and talented artist, he researched birds in their natural habitats. He captured them and sketched their likenesses on paper in life size. He gained his intimate knowledge of birds and their surroundings during a lifetime of observation in the field. His genius was in his ability to translate his vision into breathtaking paintings.

Audubon left his family in Kentucky and embarked on an expedition down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in 1819. He worked for a short time as a naturalist and taxidermist at a museum in Cincinnati and then traveled south on the Mississippi River with his gun and paintbox. In 1820, he continued into Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida in search of specimens for his collection. In the meantime, Lucy remained at home and raised their two sons.

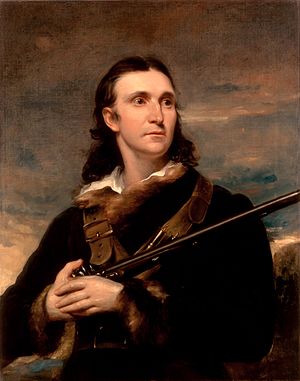

Image: John James Audubon in 1826

In the summer of 1821, he found work at Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, where he taught drawing to the young daughter of the owners of the Oakley Plantation. Though the wages were poor, he had lots of free time to hunt and paint. He attempted to finish one painting each day and sometimes hired hunters to gather specimens for him. Audubon sometimes used his drawing talent to trade for goods or quick cash. He also worked as an instructor at Jefferson College in Washington, Mississippi during the years 1822 and 1823.

Lucy the Breadwinner

Lucy Bakewell Audubon accepted the role of family provider to free Audubon to do his work. She arrived in Louisiana with her sons in 1821, and began teaching, first in exchange for room and board in a friend’s home. Later she was hired as a local teacher. From 1823 to 1830 Lucy conducted classes for young ladies, first at Beech Woods and Beech Grove Plantations in West Feliciana Parish, where she taught many of the daughters of the most prestigious families.

Lucy later founded a second school, where she was given not only a nice home but earned respect and social standing for her personal achievements. In an era when women were barely allowed to earn wages, this was a remarkable feat. In addition to a basic education, Lucy also taught music, sewing, social conduct, swimming, and horsemanship.

Finding a Publisher

In 1823, Audubon traveled to Philadelphia and New York, looking for financial support to publish his artwork, but found none. With Lucy’s encouragement, Audubon set sail for the United Kingdom in 1826, carrying with him 300 of his original illustrations. From 1826 to 1829, he traveled around the England and Europe, lecturing on ornithology, hoping to entice wealthy patrons to subscribe to his series of prints.

In the United Kingdom, Audubon finally found the financial support of pay-as-you-go subscribers, as well as the technical abilities of engravers and printers. After the very expensive folio edition had been completed, Audubon decided to produce a more affordable version. He hired J. T. Bowen, a lithographer in Philadelphia, to create a smaller edition, which was issued to subscribers in seven volumes and completed in 1844 after selling 1,199 sets. John James Audubon was an overnight sensation in the United Kingdom for his highly dramatic bird watercolors.

The Birds of America is a book of 435 images, portraits of every bird then known in the United States – painted in life size. John James Audubon worked to get this monumental book published for eleven years, from 1827-1838. The system he had invented of positioning his subjects in life-like poses using wire and thread was one of his greatest achievements. Having his subject available for hours afforded him plenty of time to sketch and paint each bird, thus contributing to his accuracy. He rarely used oil paints, the choice of most serious artists of that time, in favor of watercolors and pastel crayons, and occasionally ink and gouache.

Image: Aquatint of Common or Atlantic Puffin

From John James Audubon’s The Birds of America

Partial view of the 1833 watercolor model for the Atlantic Puffin

Photograph: New-York Historical Society

Atlantic Puffins breed on small, rocky islands off the coast of Maine. With their colorful mating beaks and crisp colorings, they look like a cross between a penguin and a parrot. They spend most of their lives at sea, coming ashore only to breed each spring and leaving again in late summer. I have fallen in love with these unusual little creatures and their sad expressive eyes.

Long Separations

Lucy had suffered separations from her husband as he traveled to New Orleans and Natchez trying to find work, and then even more after he set sail for England to publish The Birds of America. During those long years John spent abroad, coping with publishing problems, Lucy worked behind the scenes, supporting him and their sons.

Letters she wrote to Audubon illustrate the deep bitterness she felt because art was always his priority. While he spent more than three years in England, small misunderstandings grew into gigantic ones. Audubon was suffering as well. After finally finding a publisher, he had to pay production costs and supervise the engravers. He was also forced to travel all over England to sell the initial series of five prints, to make enough money to continue.

Birds of America

The first edition of The Birds of America was a remarkable achievement. The leather bound four-volume set sold for $1,070, a fortune in Audubon’s time. First published as a series in sections between 1827 and 1838, the work consists of 435 hand-colored, life-sized prints, made from engraved plates, measuring around 39 by 26 inches. The British could not get enough of his images of backwoods America. One reviewer wrote:

All anxieties and fears which overshadowed his work in its beginning had passed away. The prophecies of kind but overprudent friends, who did not understand his self-sustaining energy, had proved untrue; the malicious hope of his enemies, for even the gentle lover of nature has enemies, had been disappointed; he had secured a commanding place in the respect and gratitude of men.

Reconciliation and Success

John James Audubon eventually returned to America and reconciled with Lucy. The couple then traveled to England together. Lucy continued to help him financially – after he promised that she would share fully in future projects. The publication of Birds secured Audubon’s reputation as America’s leading ornithologist and artist. After years of struggle, he and Lucy returned to a position of status, first in England, and then in America. Once again they were accepted by family and friends, as well as artists, statesmen, and nobility.

The Birds of America had earned John James Audubon lasting fame as naturalist and painter, but its publication was costly. However, the smaller lithographed version, The Octavo, was much less expensive to produce, making it affordable for a wider audience. It also yielded higher returns that gave Audubon the means to provide a permanent home for his family.

Minnie’s Land

Audubon purchased a fourteen-acre triangle of land along the Hudson River in Upper Manhattan in 1841. He deeded the land to his wife as partial compensation for the decades of separation and hardship she had endured and called it Minnie’s Land in her honor. Minnie is a Scottish endearment for mother that the Audubon sons Victor and John began using when the family lived in Scotland while Audubon was working on his Ornithological Biographies, the companion to Birds.

At Minnie’s Land there were gardens, orchards, and livestock that provided the Audubon family with fruits and vegetables, eggs, milk, and meat. The Hudson River, a source of seafood throughout most of the year, and birds and small game were also available. Immediately after Audubon registered the deed for Minnie’s Land on October 1, 1841, his younger son John Woodhouse began to develop it into a farm and built a house near the river.

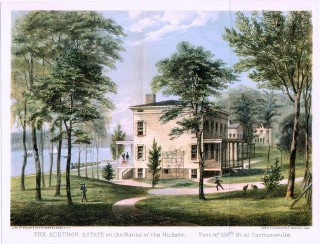

Image: Audubon Estate on the Hudson River

Contemporary Illustration of Minnie’s Land

Audubon and son Victor finished work on The Octavo edition of Birds and started his next opus, The Quadrupeds of North America. John Woodhouse constructed outbuildings and a road and cleared land for orchards and crops. In May 1842, the house was completed and the Audubons moved to Minnie’s Land; members of the family made their home there for the next four decades.

After suffering a stroke and losing his eyesight, John James Audubon died at Minnie’s Land January 27, 1851.

In 1862 Lucy Audubon presented Audubon’s watercolors to a committee at the New York Historical Society, which eventually bought many of the originals. She displayed the large works for hours, telling a story with each painting and of the hardships Audubon had endured to create it. At one point she remarked: “If I were jealous, I would have a bitter time of it, for every bird is my rival.”

Lucy Bakewell Audubon survived both her husband and her two sons; she lived long enough to raise and educate two granddaughters into young adulthood. She died June 18, 1874.

The Birds of America is the single greatest ornithological work ever produced and the culmination of Audubon’s dream of traveling throughout the United States recording every native bird known to man. Lucy Bakewell Audubon supported him, monetarily and emotionally, throughout the entire process; she deserves praise as well.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: The Birds of America

Wikipedia: John James Audubon

Pennsylvania’s Conservation Heritage: Conservation Hall of Fame

Audubon Park: A Brief History to 1886

Audubon’s Lost Paradise of Birds: Lucy Bakewell

Unique Role for Artist-Naturalist’s Wife: Lucy Audubon

New York Historical Society: Puffins: Audubon’s Lovebirds