Runaways Escaped to Freedom in Rhode Island

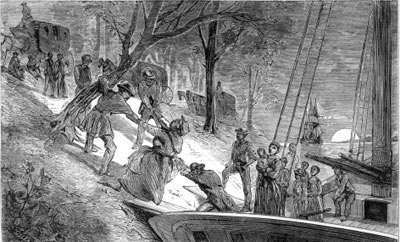

A station on the Underground Railroad

Valley Falls, Rhode Island

The Underground Railroad (UGRR) was a secret system of helping fugitive slaves escape to free states or Canada by hiding them in a succession of private homes by day and moving them farther north by night. In the 1830s, the small state of Rhode Island became increasingly involved in radical abolitionism. They were inspired by William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, the Liberator, and his call for immediate emancipation. During this period, twenty-five anti-slavery societies were formed in the state.

The UGRR was clearly not a railroad, but the participants used railroad terminology, in case they were overheard in conversation. Those who helped move the slaves from place to place were called conductors, the buildings that sheltered them were stations, those who fed and clothed them until they were ready to move on were stationmasters.

Slave Trade in Rhode Island

The colony of Rhode Island was among the most active in importing slaves. Newport was the principal slave market in all of New England. Newport alone brought almost 60,000 slaves to America before the Revolution. Merchants there sponsored more than 900 voyages to Africa between 1709 and 1807 and carried more than 100,000 slaves to the New World. Excerpt from Slavery in the North website:

Rhode Island’s government jealously protected its slaves. The runaway law of 1714 penalized ferrymen who carried any slave out of the colony without a certificate from their masters. Such laws existed in neighboring colonies, but Rhode Island’s was particularly severe in its penalties, and in the zeal with which the machinery of state was put to work in recovering human property, which was reminiscent of the hated Fugitive Slave Law of a later day. The intrenched position of the slaveholders is clearly seen in this law, for all public officers of the colony and all citizens as well were charged with arresting, securing the slave, and notifying his master.

While only a few slaves were held in the other New England colonies in 1774, Rhode Island colonists owned more than 3700 slaves. During the American Revolution, Quaker abolitionists and powerful interests in Newport shipping clashed over slavery.

In the years after the Revolution, Rhode Island merchants controlled between 60 and 90 percent of the American trade in African slaves. Slaves they did not auction off were put to work aboard merchant ships. By 1807, black seamen made up 21% of Newport crews. As one Rhode Island historian wrote:

All together, 204 different Rhode Island citizens owned a share or more in a slave voyage at one time or another. It is evident that the involvement of Rhode Island citizens in the slave trade was widespread and abundant. For Rhode Islanders, slavery had provided a major new profit sector and an engine for trade in the West Indies.

In February 1784, the Rhode Island Legislature passed a gradual emancipation law, freeing all children born to slaves after March 1, 1784. However, those children were not freed until they had served their masters as apprentices; the girls gained their freedom at the age of 18, the boys at 21. This law, therefore, gave slaveowners many years of service to offset the cost of raising the children. No slaves were emancipated outright.

Rhode Island Abolitionists

Different branches of the abolitionist movement disagreed on how to achieve their aims. But abolitionists found enough strength in their common belief in individual liberty to move forward. They used various methods including legal and political action, emphasizing slavery as a sin or simply attempting to convince the public that slavery was wrong. Public opinion of abolitionists varied widely, but the social disdain they brought upon themselves by revealing their abolitionist principles to nonbelievers was even more affecting. Excerpt from The Day newspaper:

There are vast swaths of the story of the Underground Railroad that will never be recovered. To protect thenseves, men and women, black and white, who operated the stations and undertook the incredible journeys to freedom, obliterated all written or physical evidence as the events unfolded. They were operating in defiance of established order. Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, abolitionists faced fines of $1000 and six months in jail if they were caught harboring fugitives.

Rhode Island Underground Railroad

By 1851, after the Fugitive Slave law had come into effect, many members of the African-American colony in New Bedford, Massachusetts left by the Underground Railroad for Canada. There they could be assured that they would not be captured and sold into slavery in the southern United States. This exodus passed through Fall River, then the home of Elizabeth Chace, where stations had been actively in operation since 1830. Slaves who escaped by sea from southern ports to New Bedford and towns on Cape Cod were “doubled back” to Fall River as a means of hiding the true purpose of their trip.

Fall River was home to an active roster of UGRR operatives. Robert Adams was the best-known conductor of the underground trains in Fall River though he was not a Quaker. Elizabeth Buffum Chace’s sister Sarah maintained a place for the slaves when they arrived in Fall River and cared for them until they were ready to proceed to the next stop at Valley Falls.

Prominent Quaker Israel Buffinton kept three horses available at all times, two of which were in continuous use between Fall River and the next stop on the UGRR. His son Benjamin Buffinton helped in transporting the fugitives. Quaker William Hill owned a house with a secret panel that revealed a stairway to the basement room where the slaves were hidden. The Fall River Historical Society now occupies that building.

Elizabeth Buffum Chace

In the 1830s, Quaker abolitionist Elizabeth Buffum Chace began writing a diary to record her life experiences while living in Fall River, Massachusetts. Her father Arnold Buffum, first president of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, sought the abolition of slavery by peaceful means. In 1835 Elizabeth Chace and others founded the Fall River Female Anti-Slavery Society, which was allied with the radical wing of the abolitionist movement led by William Lloyd Garrison.

Members of the Quaker Meeting of the Society of Friends at Smithfield, Rhode Island, unlike most Quakers, did not oppose slavery. When Arnold Buffum began his anti-slavery work, they called him before them and disowned him for his abolitionist views. Another Society disowned Elizabeth and her sisters for the same reason.

After Samuel’s business in Fall River failed in 1840, the Chace family moved to Valley Falls, where Elizabeth Chace opened her home to fugitives and it became the main Rhode Island stop on the Underground Railroad. She also organized anti-slavery meetings and brought well-known abolitionists to address them, including Garrison, Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, Wendell Phillips and Abbey Kelley. She detailed these activities in her memoirs entitled Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (1891), in which she wrote:

Slaves in Virginia would secure passage, either secretly or with consent of the captains, in small trading vessels at Norfolk or Portsmouth, and thus be brought into some port in New England, where their fate depended on the circumstances into which they happened to fall. A few, landing at some towns on Cape Cod, would reach New Bedford, and thence be sent by an abolitionist there to Fall River, to be sheltered by Nathaniel B. Borden and his wife, who was my sister Sarah, and sent by them to my home at Valley Falls, in the darkness of night, and in a closed carriage.

After her death, Elizabeth Buffum Chace was called the “Conscience of Rhode Island.” She was the first woman to have her statue displayed in the Rhode Island State House.

Isaac Cundall

Jacob Babcock and Issac Cundall Sr. were leaders of Underground Railroad operations in Ashaway, Rhode Island. Issac Cundall Jr. was also involved at a very young age, but his father had already taught him how the system worked. Because aiding runaway slaves was against the law, participants had to be extremely careful. To preserve the secrecy of the operation, Isaac Jr. and other conductors had limited knowledge of the system beyond their immediate vicinity – the logic being that they could not tell what they did not know.

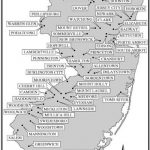

Isaac knew of only a few stations after he transported escaped slaves from his father’s house. The first of these was Jacob Babcock’s house in Ashaway. The second and third were the residences of Quakers named Foster and John Wilbour in the town of Hopkinton.

Isaac Cundall Jr. recited his memories of the UGRR – one of the very few first-hand accounts of the dangers of working on the Railroad – to a Providence newspaper in 1918. While it has been shown that fugitive slaves were primarily young men, sources indicate that many women escaped as well. It is therefore puzzling that Isaac saw only one female runaway during the years he worked on the UGRR.

The headline of the Providence Journal of January 13, 1918 read Reminiscences of Isaac Cundall. Only known survivor of the system. This is part of Isaac’s tale:

I saw but one woman slave carried over our route, and I had the fortune to be selected as her guide in March 1858. This time word was brought to me that Uncle Jacob had a woman who must be taken from the house right away, even though it was broad daylight, as Sheriff Berry … accompanied by the owner of the woman, was in our part of town looking for the runaway.

On my way to Uncle Jacob’s I met the sheriff and the slave owner, a Virginian. They showed me a large handbill, bearing a decription of the woman and offering a reward of $500 to whoever disclosed her whereabouts. “Here is a chance for you to make $500 my lad. Where is the woman?” exclaimed Mr. Berry. I told him I could not tell him that which I did not know. With this they

drove on.Upon my arrival at Uncle Jacob’s house. Mr. Babcock told me that it would be impossible for him to get the woman that night as the sheriff was watching the road too closely. “Isaac,” he said, “you must get her away from here now as soon as possible. The sheriff will get a search warrant and look through all the houses hereabouts.”

I asked Uncle Jacob if his daughter, Sarah was in the house, and … invited her to take a ride with me. I think she must have divined my purpose, for she readily accepted. At my suggestion, she pulled a heavy veil down over her face, and wrapped a big shawl about her shoulders.

We drove down the road, met Sheriff Berry, stopped and talked with him, and made it perfectly apparent that it was Miss Babcock who was with me. Sheriff Berry remarked that the weather was very cold, and I agreed with him on that point. We drove up the road for a mile, turned about and purposely met the sheriff, telling him that it was so cold that we were obliged to go back for additional wraps.

Arriving at Uncle Jacob’s, [Sarah] took off the old dress, shawl and bonnet. Directing the slave to put them on, and gave her another outside wrap to throw over her shoulder. We made another start this time the heavily veiled slave being on the seat beside me.

Up the road we met Sheriff Berry. He seemed to persist in watching that part of the highway. As we reached him, I exclaimed, “Now we are off.” “Good luck to you,” the sheriff shouted as we drove off.

I carried her to Preacher John Wilbour’s house, a short distance beyond Hopkinton, and that night I was told she was taken on to the next station.

Though estimates vary widely, at least 30,000 slaves, possibly more than 100,000, escaped to Canada via the Underground Railroad, and settled there, mostly in Ontario. Many fugitives were disappointed that life in Canada was so difficult competition for jobs was intense. The British colonies had outlawed slavery in 1834, but widespread, overt discrimination was still common.

Runaway slaves moving carefully through the forest

SOURCES

Phillips History of Fall River – PDF

Elizabeth Buffum Chace Family Papers

Rootsweb: Underground RR in Rhode Island

Slavery in the North: Slavery in Rhode Island

The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom

The Day: Underground Railroad is Branching Out Today

We today cannot imagine what people endured for a sliver of freedom