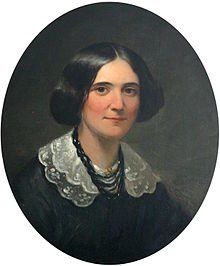

Author and Newspaper Columnist

Mary Clemmer Ames gained national notoriety as a Washington correspondent by attacking politics in the Gilded Age (1870s-1900). Despite her success as a journalist, a mostly male occupation, Ames supported the nineteenth century ideal that a woman’s proper place was in the home.

Early Years

Born May 6, 1831 in Utica, New York, Mary Clemmer was the eldest of a large family of children of Abraham and Margaret Kneale Clemmer. Her father’s ancestors were Alsatian Huguenots and her mother emigrated to Utica from the British Isle of Man. In 1847 the Clemmer family moved to Westfield, Massachusetts where Mary attended the Westfield Academy, but her family’s financial woes ended her education.

On May 7, 1851, Mary Clemmer married Daniel Ames, a minister with pastorates in New York and Minnesota. It was not a good match. They were extremely incompatible and lived apart from time to time. A biographer claimed that Mary was “desperately unhappy … even to the point of contemplating suicide.”

Career in Journalism

In 1859 Mary left Daniel Ames temporarily and moved to New York City, where she lived with two sisters, Phoebe and Alice Cary, both poets and authors from Ohio. The sisters introduced Mary to their literary circle, as well as Horace Greeley and other editors, sparking her interest in writing as a means of supporting herself. In 1859 she began sending letters from New York City to several newspapers, including the Republican in Springfield, Massachusetts and the Utica Morning Herald in her hometown, hoping to generate some interest in her writing.

Civil War

Ames reunited with her husband during the Civil War and served as a nurse in Union hospitals in Washington DC, while developing close friendships with important political figures. She was at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1862 because of her husband’s ministerial duties. During the Battle of Harpers Ferry in September 1862, she recorded what she witnessed. Her account of the battle, “The Battle of Harper’s Ferry As a Woman Saw It,” was published in The New York Evening Post on September 26, 1862. This excellent article can be read in its entirety at the California Digital Newspaper Collection. This is an excerpt:

We were eating our breakfast in a comfortable home on Camp Hill on Saturday morning, the 13th of September, when we heard the quick, cruel ring of musketry cutting the air. We ran out upon the hill in the rear of the house overlooking the village below, London Heights [Loudoun Heights, the second highest mountain overlooking Harpers Ferry], the Shenandoah, the Potomac, the Heights of Maryland, a vast green precipitous wall, on the opposite shore. [Stonewall] Jackson had come; come to the only spot where he could effectually besiege our stronghold. We strained our eyes through the blue of that transcendent morning to the sunlit woods above us, echoing with death. Volley after volley shivered the air, and with it the bodies of men. At first the report was far up, almost on the mountain top; then it drew nearer, rattling louder, and we knew the foe was advancing; we heard his hellish war cry; we heard Dixie shrieked by thousands of barefooted fiends. …

Newspaper Columnist

When the Civil War ended, Mary left Daniel Ames permanently and moved to Washington DC. On March 4, 1866, the New York City Independent, an influential weekly newspaper, published the first Woman’s Letter from Washington by Mary Clemmer Ames. She received immediate praise and national acclaim for this column, which she continued to write for nearly two decades.

True Woman

Yet Ames was ambivalent about her success, claiming that her career resulted from financial necessity. She pointed out that fame did not appeal to a true woman and success in a profession might extract a higher price than a womanly woman wanted to pay:

If she offends as an artist, it is her misfortune to be assailed as a woman, because, as a woman, nothing can be so sacred to her as her womanhood. Fame is a curse which soils the loveliness of the womanly name by thrusting it into the grimy highway, where it is wondered at, sneered at, lied about, by the vulgar, the worldly, and the wicked.

Ames insisted that she shrank from public attention because she was a true woman, who loved quiet domesticity. She was quoted as saying:

The best thing that can happen to any woman is to be satisfactorily loved, to be taken care of, to be made much of, and to make much of the life and the love utterly her own in her own home.”

However, Mary Clemmer Ames did use her gender in pursuing her career, insisting that a woman exemplified a purity that could not be expected of a male journalist. She achieved success without sacrificing her femininity, promoting the idea that women’s morals were more pure than men. She maintained that it was her womanly duty to campaign for an elevation of public life in her columns. She described the role of a woman correspondent: “It is her work to help exalt the standard of journalism, and to preserve intact the dignity and sweetness of individual womanhood.”

Obviously, Mary Clemmer Ames did not lead the life she advocated. She divorced Daniel Ames in 1874 and took back her maiden name, but has since been known professionally as Mary Clemmer Ames. She earned her living as a writer, cultivating contacts with political figures to generate news for her newspaper columns. Ames was described as:

Personally timid and sensitive to criticism, she was capable, nevertheless, of sharp condemnation of political leaders whose conduct failed to measure up to her standards of rectitude.

Unlike some other women journalists (like Sara Lippincott who wrote for the New York Times as Grace Greenwood), Ames did not use a pseudonym. She signed her columns either with her initials or her full name.

Ames wrote hundreds of articles for her column based on events in Congress, which she watched from the ladies’ gallery. Although she was permitted to sit in the Capitol press galleries, she did not do so, as she explained to her readers:

Because a woman is a public correspondent it does not make it at all necessary that she as an individual should be conspicuously public – that she should run about with pencils in her mouth and pens in her ears; that she should invade the Reporters’ Galleries, crowded with men; that she should go anywhere as a mere reporter where she would not be received as a lady. It is a class of women who … choose to do all that they do in a loud, intrusive manner, who provoke antagonism and bring reproach upon an entire class.

According to the U.S. Congressional Directory, at least twenty women (twelve percent of the current 166 correspondents) were allowed to sit in the press galleries of the U.S. Congress. However, at that time most of these women were writing about social events during the Ulysses S. Grant presidency. Ames distanced herself from these women. Of the entire group, Ames earned the most and enjoyed the longest career.

During the time she wrote for the Independent, it was one of the most influential newspapers in the country, and her articles only enhanced its influence and circulation. Managing editor Oliver Johnson informed her in 1867 that he and chief editor Theodore Tilton were extremely pleased with her work. In a letter to her, Johnson quoted Tilton as saying, “I find also in my travels much commendation expressed of Mrs. Ames’ letters. She is your card, and she is a trump.”

Ames received many letters from admiring readers. A minister wrote: “the clergymen of our common country can find no better aid outside of God and the Bible than the light given upon moral subjects from such pens as your own.” Publisher of The Free-born County Standard in Minnesota wrote, “I would to God every Washington correspondent had your independent, fearless makeup.”

In addition to her political commentary, Ames wrote both poetry and prose, including novels. Her works include: Victoire (1864); Eirene; or A Woman’s Right (1870); Ten Years in Washington (1871); Outlines of Men, Women, and Things (1873); His Two Wives (1874); Memorials of Alice and Phoebe Cary (twenty-sixth edition, 1885); and Poems of Life and Nature (1886).

Women’s Rights

Like most other nineteenth-century advocates of women’s rights, Ames never imagined a time when women would adopt the same moral standards as men. Instead, men would be raised to the pure level of women. She believed that women should have the right vote but objected to any other role for women in politics. Suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker stated that she would remain in Washington until the Senate agreed to listen to her plea for women’s right to vote. She received no sympathy from Ames, who believed that suffrage was less important than economic gains, saying, “Woman can live nobly without voting; but they cannot live without bread.”

Ames championed the right of women who lacked a man to support them to work in gainful occupations. She urged unmarried and unoccupied women to enter the medical field, arguing that the art of healing would develop their true womanly sensibilities. She was disturbed by inequalities in pay between the sexes, stating that men with families dependent on them should be paid well, but women who supported households were always paid less.

She was pleased when Rutherford B. Hayes was inaugurated as President in 1877, but she was angered when she learned that women government employees were being dismissed. But by the following year she was again enthusiastic for Hayes. Ames described First Lady Lucy Webb Hayes as the embodiment of purity and praised her for her many virtues throughout the four-year administration.

Ames was a prolific author, especially during the 1870s, when she published two novels and three volumes of non-fiction, based largely on her Washington columns. From 1869 to 1872 she wrote for the Brooklyn Daily Union in addition to the Independent, both of which were published by Henry Bowen. Bowen was so impressed by Ames that he paid her $5,000, the largest salary ever paid a newspaper woman up to that time.

Late Years

In the mid-1870s, Ames purchased a large brick house on Capitol Hill in Washington DC. She lived there with her aged parents, enjoying her social position as a literary lady. After she had stopped working for the Brooklyn paper, Ames became a Washington correspondent for the Cincinnati Commercial, while still writing for the Independent.

Within a few years, under the pressures of her career, her health began to fail. Severe headaches caused by overwork began to afflict her in 1875. In 1878, she was riding in a carriage when the horses bolted. Panicked, she jumped from the carriage and received a skull fracture. After the accident, she curtailed some of her work but continued to write her columns and published a book of poetry.

On June 19, 1883, Mary married Edmund Hudson, a well-known Washington journalist who edited the Army and Navy Register.

Mary Clemmer Ames died of a cerebral hemorrhage in her Washington home August 18, 1884, fourteen months after her marriage. She was 53 years old.

Her journalistic accomplishments were praised in numerous obituaries including those in the New York Times, Boston Traveller, The Nation, the Washington Evening Star, Arthur’s Home Magazine and The Literary News.

A lengthy eulogy in the Independent described Ames as a slender, graceful and dignified woman with blue eyes and light-brown hair. It stated that she began writing newspaper columns for two dollars each and was earning at least forty dollars or more per column at the time of her death. The tribute also praised her for being a remarkably womanly woman who “loved home cares, to attend to the house, to go to market, to dress with a woman’s elegance, to identify herself with a woman’s life and woman’s duties and hopes.”

Senator Justin Morrill wrote in a eulogy:

Mary Clemmer has been the trusted friend of many eminent men – of Sumner, of Whittier and of Garfield . … She made herself a power believed and feared.

Mary Clemmer Ames was successful as a journalist because she transformed her gender from a liability to an asset. By insisting that she was not just a journalist, but a true woman, she took advantage of the ideal that women possessed higher morals than men. Therefore, women had the right to comment on public affairs if she did so in the name of morality.

SOURCES

Battle of Harper’s Ferry as a Woman Saw it

Mary Clemmer Ames: A Victorian Woman Journalist