Slaves Escaped the South on Northern Vessels

The Maritime Underground Railroad was a network of people who helped slaves travel by vessel from the southern United States to freedom in the North and Canada. Slaves escaped aboard the thousands of Southern ships that did business in the North and sailed regularly up and down the Atlantic coast. A clandestine society of slaves directed fugitives to the ships and black crewmen secreted them on board.

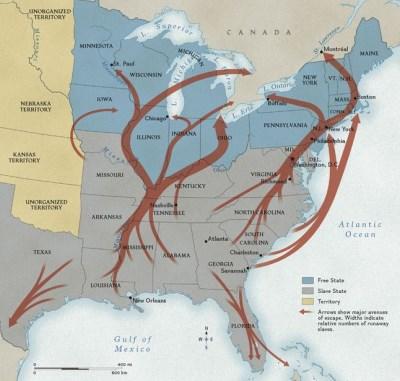

Image: Underground Railroad Routes on Land and Sea

Credit: National Geographic

Coastal Trade

Historical terms coastal trade, coastal shipping, coasting trade, coastwise commerce and coastwise trade all refer to vessels that moved cargo and passengers by sea along a coast, or trade carried on between neighboring ports of the same country. According to historian David Cecelski, author of The Waterman’s Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina:

Maritime routes of the Underground Railroad were vital for thousands of fugitives who stowed away, impersonated free black mariners, bought passenger tickets, or enlisted the aid of sympathetic captains and crewmembers. Runaways depended on maritime blacks. …

Convinced that slaves regularly escaped aboard northern vessels, Southern legislatures passed numerous Negro Seamen’s Acts from 1822 into the 1840s. These laws were meant to curb the free movement of northern black crewmen in southern ports, presuming that they were enticing slaves to escape, but blacks continued to work on ships involved in the coastal commerce.

The editor of a Norfolk newspaper in 1850 charged that virtually the entire coasting trade was “in the hands of Northern abolitionists” and that free black crewmen on those ships gave slaves “notions of freedom, and afterwards afford[ed] them the means of transportation to free soil.” The agitated editor went so far as to allege that some vessels “actually [made] the abduction of slaves a matter of trade and a source of profit.” Southern newspapers, not only those in Norfolk, complained throughout the 1850s that slaves were regularly escaping on northern vessels.

Maritime Escapees

Some of the best-known fugitives traveled to the free states by coastal vessel. Moses Roper, a steward on a New York ship, escaped while in New York City and continued to use the Maritime Underground Railroad to elude slave catchers. A slave named Daniel Fisher left South Carolina on a lumber vessel headed for Washington, DC. He went from there overland to Baltimore, Pennsylvania, and New York and then by steamboat to New Haven. After changing his name to William Winters, he left Deep River, Connecticut, bound for New Bedford, Massachusetts.

New Bedford, Massachusetts

In the 1790s New Bedford captains began placing newspaper notices of men of color who had stowed away on their ships to clear themselves of any responsibility for the escapes. They typically claimed that they were unaware of the stowaways’ presence until well after they had set sail and that, the “wind being ahead,” it was impractical to turn around and bring them back. As early as 1819 runaways were arriving at New Bedford by water. By 1851 the six or seven hundred black residents of the town were primarily refugees.

In the years before the Civil War, New Bedford carried on a very busy coastal trade with southern states. Therefore, people of color were much more apt to reach the city aboard coastal vessels because traveling on foot through the bays and swamps along the southern Atlantic coast was very difficult. These ships carried oil and New England products to exchange for raw goods in the South, and northern states depended heavily on these materials. The South also provided barreled beef and pork, rice, corn, tobacco and cotton to northern states.

For years the Cape Fear region of North Carolina lacked an adequate port, so its raw materials were often shipped through Norfolk, Virginia, also the port through which the largest number of known fugitives escaped to New Bedford. A coasting vessel could make the trip from Norfolk to New Bedford in four or five days. Several white captains – including Alfred Fountain of the steam packet City of Richmond and William Bayliss of the Kesiah – were famous for carrying fugitives in groups of a dozen or more. All but Fountain were eventually arrested and imprisoned.

White Pigeon

According to abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “fugitive slaves commonly came by water, as stowaways in vessels”; those who traveled by land usually went through Ohio. Higginson told historian Wilbur Siebert about a vessel known as the White Pigeon, which was operated as an excursion boat in Boston Harbor, but its real purpose was to carry fugitives aboard cotton vessels to shore in the dark of night. The White Pigeon was operated by Austin Bearse, who had worked in the coasting trade between Cape Cod, New Bedford and Boston and southern ports until he could take it no longer. He had seen slavery in Spanish and French ports and in Algiers and Smyrna among the Turks, but, he wrote:

My opinion is, that American slavery, as I have seen it in the internal slave trade, as l have seen it on the rice and sugar plantations, and in the city of New Orleans, was full as bad as any slavery in the world – heathen or Christian. People who go for visits or pleasure through the Southern States, cannot possibly know those things which can be seen of slavery by shipmasters who run up into the back plantations of counties, and who transport the slaves and produce of plantations.

While living in New Bedford, Bearse began to subscribe to the Liberator; he became an agent of the Boston Vigilance Committee and dedicated himself to helping fugitives or impeding their capture. Higginson told Siebert that members of the Committee would:

… run the boat down in the harbor to meet Southern vessels. The practice was to take along a colored woman with fresh fruit, pies, etc. – she easily got on board and when there, usually found out if there was any fugitive on board; then he was sometimes taken away by night.

Such a subterfuge worked because black men and women were ordinary sights along the waterfronts of all coastal cities in the North and South, to say nothing of how commonplace black mariners were on board ships of all kinds.

Image: Harriet Tubman Escorting Slaves into Canada

By Jerry Pinkney

Edenton, North Carolina

In the years before the Civil War, ports like Edenton, North Carolina were crowded with black seamen, many of whom worked to identify sympathetic crewmen who would arrange passage for enslaved persons on ships from a free state. On most ships, blacks worked as stewards and cooks; some held skilled positions. Ferrymen who conveyed passengers and goods from the docks to ships in the bay were nearly always slaves.

Historian David Cecelski has stated that he found:

Several dozen accounts of specific runaway slaves who reached ships sailing out of North Carolina ports between 1800 and 1861. … one may safely conclude that they represent only the tip of an iceberg. The presence of an escape route along the East Coast was indeed widely known both locally and among northern abolitionists who, though it operated independently of them, frequently assisted fugitive slaves after their voyage from the South. …

At the wharves, slave women peddled fish, oysters, stew and cornbread to hungry sailors and found a ready market for laundry services. Slave artisans caulked, refitted, rigged and rebuilt as necessary to keep wooden vessels at sea. Their maritime culture provided runaways with a complex web of informants, messengers, go-betweens and other potential collaborators.

Harriet Jacobs

In her memoirs, Harriet Jacobs revealed how the African American community, including black seamen, arranged for her escape from Edenton, North Carolina. By 1842 Jacobs had been hiding in a tiny crawl space in her grandmother’s house for one week short of seven years – without the knowledge of her children who were living in the same house or her owner who was living a few blocks away – when she finally summoned the courage to escape. She sent a message to her friend Peter, who arranged with the captain of a schooner to take her North.

At the wharf that night, Harriet’s Uncle Mark rowed her out to the anchored ship in Edenton harbor, and the captain “showed her to a little box of a cabin.” He advised her to stay in her cabin whenever a sail came in view, but otherwise she might be on deck; by the third week of June she stepped ashore in Philadelphia. She then traveled by railway to New York, where she was soon reunited with her daughter and her brother, who had previously escaped to the North. Her son joined the family in Boston a year later.

In New York City in 1842, Mary Stace Willis hired Harriet Jacobs to watch over her new baby. Mary was the wife of Nathaniel Parker Willis, a writer, poet and editor who worked with several famous authors including Edgar Allan Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Willis also founded a magazine called the Home Journal which he edited until his death in 1867, when it was renamed Town and Country in 1901 and is still published today. His brother, Richard Storrs Willis was a composer and his sister Sara wrote under the pseudonym Fanny Fern. Jacobs did not tell Mrs. Willis that she was a fugitive slave.

For a short time Jacobs and her brother John lived and worked in Rochester, New York at the Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room, where they became acquainted with Frederick Douglass, Amy Kirby Post and other abolitionists. With Post’s encouragement, Jacobs began working on a manuscript about her days as a slave, which she published as Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent.

After living for a while with abolitionists in Rochester , Jacobs returned to New York City in 1850, where she was pursued by her owner. With the recent passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, Jacobs lived in constant fear that she would be caught and returned to slavery. Legally, she was still an escaped slave.

Jacobs returned to New York City to work for the Willis family again in 1850, but Mary Stace Willis had died in 1845, and Nathaniel Parker Willis married Cornelia Grinnell Willis in 1846. When Cornelia Willis eventually learned of Jacobs’ fear of being caught and returned to her owner, she bought Jacobs for $300 in 1852, and then freed her. Harriet wrote:

My heart was exceedingly full. I remembered how my poor father had tried to buy me, when I was a small child, and how he had been disappointed. I hoped his spirit was rejoicing over me now. I remembered how my good old grandmother had laid up her earnings to purchase me in later years, and how often her plans had been frustrated.

During most of the 1860s, Harriet performed relief work, first nursing black troops and teaching, and later, aiding freedmen in Washington, DC, Savannah, Georgia, and Edenton. Later, Harriet and her daughter lived in Washington, DC, where Louisa Matilda participated in organizing meetings of the National Association of Colored Women. Harriet died March 7, 1897 in Washington, DC, and was buried next to her brother in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge.

The Gunboat Planter

On May 12, 1862, the entire white crew of the CSS Planter, an armed Confederate military transport, decided to spend the night ashore in Charleston, South Carolina. Before the war, at 147 feet long, the Planter had been a cotton steamer, capable of holding 1400 bales of cotton. It now took supplies to Confederate forts in Charleston Harbor as a special dispatch boat for Brigadier General Roswell Ripley, port architect and commander of the second military district of South Carolina. Ripley was second in command to General P.G.T. Beauregard.

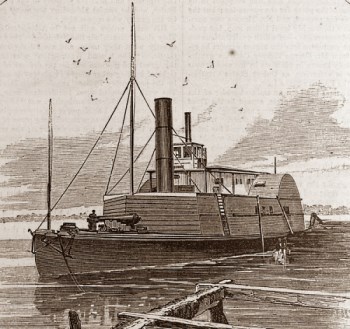

Image: CSS Planter

In Charleston Harbor

The African American pilot of the Planter, Robert Smalls, had keen navigational skills, which had earned him the job in March 1861. When the white men announced they were going ashore on unauthorized leave, trusting in the loyalty of the black crewmen, Smalls and the seven other enslaved crewmen on board decided to try to escape to freedom by sailing toward the Union flotilla that blockaded the harbor. As soon as the white crew were out sight, Smalls and his crew left the dock, which was directly below General Ripley’s house and office. Smalls donned the captain’s uniform and straw hat, and sailed the Planter to a nearby wharf, where they picked up Smalls’ wife and children and relatives of other crew members.

At around 3 o’clock on the morning of May 13, 1862, twenty-three-year-old Robert Smalls guided the CSS Planter out of Charleston Harbor and became part of the Maritime Underground Railroad. No one challenged the ship on its way to Fort Sumter, the fifth Confederate fort that protected the Harbor, but Smalls feared that a Confederate officer at Sumter would be suspicious because of the early hour. While some crew members begged him to change his course, Smalls steered the Planter directly beneath the walls of Fort Sumter.

Smalls kept to the shadows inside the pilothouse, hiding his face under the brim of the captain’s hat. Smalls blew the steam whistle twice and waved to the guards standing 40 feet above. “Pass the Planter,” shouted one of the Rebels. “Blow the damned Yankees to hell, or bring one of them in!” Smalls shouted out “Aye, aye!” And the Planter sailed on out of the range of the cannons.

As he approached the Union flotilla, Union sailors noticed that Smalls was now flying a white flag of surrender made from a bed sheet and held their fire. The steamboat approached the nearest Union ship, the USS Onward, and Robert Smalls announced to its captain his wish to be free and to serve the United States Navy. At about dawn, Smalls turned over the Planter, its two guns and cargo of artillery pieces, and a Confederate code book and locations of mines in the Harbor. Smalls also provided invaluable firsthand intelligence about Charleston and Confederate defenses.

On May 13, Smalls spoke with Admiral Samuel Du Pont, who afterwards wrote to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles:

This man, Robert Smalls, is superior to any who has yet come into our lines, intelligent as many of them have been. His information has been most interesting, and portions of it of utmost importance. … I shall continue to employ Robert as a pilot on board the Planter for inland waters.

Smalls became famous throughout the North. He met President Abrahan Lincoln, and he and his crew received substantial prize money for capturing the Planter. His story was used as an argument for allowing blacks to serve in the Union army. In April 1865, Smalls returned with the Planter to Charleston Harbor for the ceremony that raised the American flag over Fort Sumter once again. Later in life he would serve in both the South Carolina State Legislature and the U.S. House of Representatives.

SOURCES

Harriet Jacobs Biography

Voyage to Discovery: Escape

Robert Smalls and the Gunboat Planter

Mrs. Willis Buys Freedom of a Slave Girl

The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts – PDF

Really wish this blogpost had more info on who historian Wilbur Siebert was, date of his book, etc and a link to the source. We just learned on 9/10/22 of his massive 1898 book “The Underground Railroad, from Slavery to Freedom, A Comprehensive History.

Here’s a link to a digitized copy for the benefit of other researchers

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/49038/49038-h/49038-h.htm#Page_33