Quakers Ran the Underground Railroad

In the seventeenth century, to the Englishmen who first settled Long Island, slavery was an accepted way of providing the labor force needed for agriculture and a comfortable life. After the arrival of the Quakers in the eighteenth century, attitudes were changed and the Underground Railroad began guiding slaves to freedom.

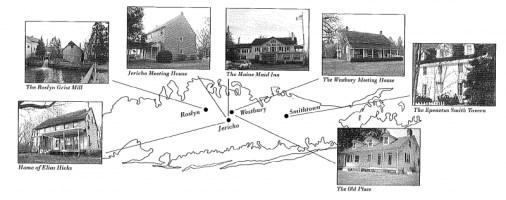

Image: Map of Long Island towns on the Underground Railroad

Long Island

Stretching east-northeast from New York Harbor into the Atlantic Ocean, Long Island comprises four counties: Kings County (Brooklyn) and Queens County (Queens) in the west, then Nassau County and Suffolk County to the east. The Island is 118 miles long from east to west and about 20 miles at its widest point, the largest island in the continental United States. It is separated from the mainland on the north by Long Island Sound and bounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the south and east.

The East End of the island is made up of two forks. The North Fork is approximately 28 miles long, the South is about 44 miles in length. Peconic and Gardiners Bays separate the two forks, where Shelter Island and Gardiners Island are located. In 1771, blacks accounted for 17 percent of Long Island’s population, and virtually all were enslaved. By 1790, when the first federal census was taken, 54.8 percent of Suffolk County slave owners had one slave, and 88.7 percent owned fewer than five.

Queens Freedom Trail

Running east from Queens to Long Island and then north-northwest to Westchester County is the Queens Freedom Trail. Quaker families were separated during the Revolutionary War as their men left home to escape capture by the British Army, thus leaving their wives and children behind in hopes of saving their homes being used as barracks by the British. The surreptitious return of these men from time to time to check on their families created a network of paths for escaping slaves who later sought sanctuary at the homes of Quaker farmers who transported desperate fugitives in their wagons.

Under cover of darkness, they traveled north along the trails to help runaways secure safe passage on a boat to Westchester County, New York, from which they journeyed farther north with the aid of other Quaker communities. Another path followed the shores of Long Island, where thick brush and tall grasses concealed runaways as they made their way to the Quaker community of Jerusalem. These first tentative steps by Queens and Long Island Quakers were among the earliest efforts to free slaves in America.

In 1852, when runaway Harriet Jacobs learned that her North Carolina master had come to the boarding house where she was living and searched for her, she panicked. Jacobs had not told her current employer, Cornelia Grinnell Willis, wife of writer Nathaniel Parker Willis, that she was a fugitive slave. However, Cornelia Willis acted quickly to help Jacobs escape by buying her a ticket on a steam boat in Queens that was headed across Long Island Sound to New Haven, Connecticut. Within hours she was safe… for the moment.

Westbury

In 1657, Captain J. Seaman purchased 12,000 acres from the Algonquian Tribe of the Massapequa Indians. In 1658, Richard Stites and his family established the only family farm until English Quaker Edmond Titus settled in an area of Hempstead Plains now known as the Village of Westbury in Nassau County, Long Island. Other Quaker families looking for a place to freely express their religious beliefs joined those early settlers, and they owned slaves. The first Society of Friends meeting house was built in 1700.

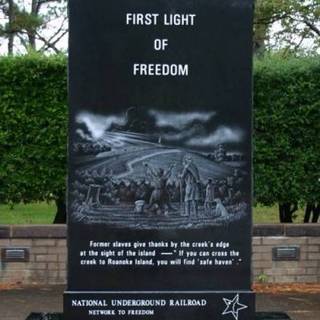

Image: Hay wagons with false bottoms

Groups of escaping slaves were transported on these wagons from New York City to Westbury, where they were given shelter until they could be transported to boats on the Long Island Sound, which would take them farther north.

Elias Hicks was an early Quaker abolitionist. At Westbury Meeting House, he spoke in 1775 and convinced the members of Westbury to liberate their slaves. Hicks and his Quaker neighbor Phebe Willets Mott Dodge manumitted their slaves. Manumission is the act of a slave owner freeing his or her slaves. They were the first Quakers at Westbury Meeting to do so. Other Quakers were compelled to free 154 African American slaves. All Westbury slaves were freed by 1799.

Long Island slaves were often given the opportunity to learn a skill, and many became property owners after they were given their freedom. Many of these freed men and women built homes, farms and dairies on the open land near the sheep grazing pastures. In 1794, Elias Hicks was a founder of the Charity Society of Jerico and Westbury Meetings, established to give aid to local poor African Americans and provide their children with education. In 1834, with Quaker assistance, they built the New Light Baptist Church.

By 1837, the Long Island Railroad had built through Westbury, which made it easier for German, Italian, Irish and Polish immigrants to work Westbury’s farms. At the same time more African American families came to the area via the Underground Railroad. For some, Westbury was only a stop on the way to Canada, but some stayed in the area after being harbored in secret rooms in the homes of the Quakers. In 1840, the first public school was built.

Valentine and Abigail Hicks

Almost a century before it became a restaurant called the Maine Maid Inn, this building in Jericho, Nassau County, Long Island was the home of Valentine and Abigail Hicks, prominent members of the Quaker community who founded the town of Jericho. Valentine Hicks purchased the home in 1814 and moved here from New York City with his wife and their daughters.

Hicks was Postmaster of Jericho from 1826 to 1839, and the Post Office was probably located in the Hicks’ front parlor during those years. In 1837, he was elected second president of the Long Island Railroad, and was instrumental in bringing rail service to the area. The town of Hicksville was named in his honor.

Valentine Hicks was also an Underground Railroad station master. Historians say this was the most prominent stop on the Underground Railroad on Long Island. He employed former enslaved people on his farm, was a member of the Manumission Society, and helped establish the first African Free Schools.

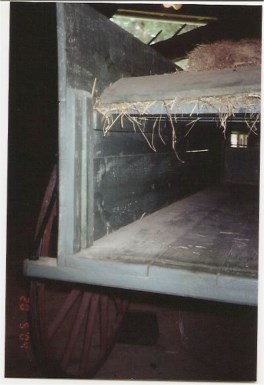

Image: Home of Valentine and Abigail Hicks

Also a station on the Underground Railroad

1840s photo of Hicks and his family on the front lawn

As Hicks looked out his window one day he saw a slave running down the road pursued by a slave catcher. Acting quickly, Hicks opened his door, and the man ran inside. Because Quakers in the area had often been robbed by early town sheriffs and tax collectors, it had become common for them to hide their valuables in clever places. In the Hicks house, a large panel inside a second-floor linen closet could be removed to reveal a set of steep and narrow stairs to the attic above, and once the panel was replaced, it was impossible to discover the ruse.

Hicks hurried the fugitive slave up the steep stairs to the attic and safely hid him there. After he had a rest and an evening meal, the family took the runaway by hay wagon to Long Island Sound after dark. There he boarded a boat to Westchester or Connecticut and north to Canada, with stops at other Quaker homes along the way. The family is also said to have transported fugitive slaves across Long Island Sound, if necessary.

Shelter Island

And then way out east in Suffolk County, between the North and South Forks lies Shelter Island. The first slave plantation on Long Island, as well as the largest, Sylvestor Manor began on Shelter Island in 1651, when English Quaker Nathaniel Sylvester brought 24 slaves to work the land so he could provide for his brother’s two large sugar plantations in Barbados. He raised food crops, as well as livestock for slaughter, shipping huge barrels of meat and supplies to his brother.

In 1652 Sylvester built the original house on the island for his 17-year-old bride, Grizzell Brinley from London, and it provided a home for Nathaniel and Grizzell Sylvester, their eleven children and most likely several slaves and indentured servants. In the 1730s their grandson Brinley Sylvester constructed the elaborate manor house, which was extensively renovated in the 1840s and still stands today.

While conducting fieldwork at the site off and on for almost fifteen years, researchers discovered that Sylvester Manor was not a typical Southern plantation. Native Americans, Africans, and English indentured servants lived and worked closely together when Sylvester owned all 8,000 acres of Shelter Island. Sylvester’s descendants continued to use slaves on the plantation into the 19th century. An estimated 200 blacks are buried at the Negro Burying Ground on the North Peninsula.

Cultural landscape historian Mac Griswold and a friend were rowing down Gardiners Creek on Shelter Island in 1984 when she came upon Sylvester Manor, a mansion guarded by huge boxwood hedges that were centuries old. The aged owner Andrew Fiske showed her inside and pointed out the slave staircase, which led from the west parlor to the attic. In 1997, Griswold returned with a team of archaeologists, and they uncovered a landscape filled with stories.

Image: Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island

The owners of this stately mansion on Shelter Island once commanded an 8,000-acre slave plantation. Today Sylvester Manor is a non-profit educational foundation, an organic farm, and a major archaeological site.

End of Slavery on Long Island

Quakers were the first organized group of whites to voluntarily hasten the end of slavery on Long Island in the 18th century. Elias Hicks and his son-in-law Valentine were among the most active in this movement. According to Joysetta Pearse, executive director of the African Museum of Nassau County, Quakers used their influence to bring about social change:

If an editor of a local paper ran an ad for a runaway slave – and slaves did run away from Long Island slaveholders – Long Island Quakers would write to the editors that they would boycott the papers if the editors continued to run the slave notices. … They did all the harassing they could do, and the [state] legislature finally moved to address the issue.

The New York legislature amended its gradual manumission law in 1817 so that all enslaved blacks in New York would be free as of 1827.

But fugitives from the South being pursued by their owners or slave catchers still needed the assistance of Long Islanders on their way to freedom. The stakes increased dramatically for operators of the Underground Railroad after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, which mandated that runaway slaves be returned to their owners no matter where they were discovered, even in northern states. Escorting fugitives to the next station on the UGRR became even more dangerous for both slaves and conductors. They could not trust anyone.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Elias Hicks

Wikipedia: Westbury, New York

Long Island Journal: Way Stations on Freedom’s Road

Slavery and Salvation: Long Island’s Underground Railroad

Underground Railroad Teaching Partnership of Long Island