Ohio was the Promised Land

According to Ohio State University history professor Wilbur Siebert, Ohio had the most estensive Underground Railroad network of any other state, with an estimated 3000 miles of routes used by runaways. There were more that twenty points of entry on the Ohio River, and as many as ten exit points along Lake Erie.

Image: Underground Railroad Monument

Created by Cameron Armstrong at Oberlin College

Terminology

The Underground Railroad did not run on tracks, nor was it under ground. The word underground was used because helping escaped slaves was illegal and must be kept secret. The word railroad spawned other terms to describe people and places associated with the practice of assisting runaway slaves:

• Slaves are cargo or passengers.

• Hiding places or safe houses are stations.

• Guides leading the fugitives to the next stop are conductors.

• People helping the escaping slaves, but not guiding them, are agents.

• People providing financial resources for these activities are stockholders.

Backstory

The Underground Railroad (UGRR) was a system of safe houses, hiding places and backwoods paths that helped fugitive slaves escape to freedom in the northern United States or Canada. It remains unclear when the Underground Railroad began, but Quakers in Ohio were actively assisting fugitive slaves as early as the 1780s.

Additional Ohio residents were helping fugitive slaves by the 1810s. Participants only knew about a few connecting stations along the route. Escaped slaves moved north from one station to the next. Conductors on the railroad came from various backgrounds and included free-born blacks, white abolitionists and former slaves.

Owning slaves had been illegal in Ohio since the constitution of 1802, but some Ohioans still supported slavery. They feared that former slaves would move into the state, take jobs away from the white population, and demand equal rights with whites. These activists vehemently opposed the Underground Railroad; some attacked conductors; others tried to return fugitives to their owners in hopes of collecting rewards.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 permitted slave owners to reclaim fugitive slaves, even if they had moved to a free state. This law increased the danger that free blacks would be kidnapped and forced into slavery. Therefore, many African Americans believed that to truly gain their freedom they had to leave the United States.

On the last leg of their journey to Canada, runaway slaves were led by conductors to the northernmost part of the state of Ohio – the last stop before they were ferried across Lake Erie to freedom in Canada. Several towns along the lake were commonly used as exit points, including Toledo, Cleveland, Sandusky, Ashtabula Harbor and Lorain.

Blacks Ran the Underground Railroad

While white abolitionists played an important part in their escape, the role of free blacks in the activities of the UGRR cannot be overstated. Without the presence and support of free blacks, there would have been almost no chance for fugitive slaves to pass into freedom unmolested. They rarely trusted even well known abolitionists with news that a new group of slaves was passing through.

In a letter to Lewis Tappan in February 1837, James G. Birney, white publisher of the abolitionist newspaper The Philanthropist, commented:

The Slaves are escaping in great numbers through Ohio to Canada… Such matters are almost uniformly managed by the colored people. I know nothing of them generally till they are past.

A Long and Difficult Journey

Winter was the optimum time to escape. Work schedules were relaxed, and slaveholders often traveled during the holidays. Slaves were given passes to visit family who lived on other properties. Fewer people were on the roads because of the cold weather, but there was little foliage in the winter landscape. Hiding in the woods by daylight and traveling only at night, escaping slaves were especially vulnerable until they reached a border state.

The Ohio River regularly froze over, which made it possible for runaways to walk across the ice to freedom, but the ice was often more like large chunks of floating ice that required careful footing to make it safely across the river in the dark. Once they crossed the Ohio River, they had to make contact with someone they did not know, and hope that they would provide them food, shelter and rest, and then lead them to the next station.

Escapees also had to avoid slave catchers, roaming bands of bounty hunters who scoured the countryside in search of fugitives. This had become a big business that paid huge dividends when a runaway was captured. Under the Fugitive Slave Law, slaves could be tracked and returned from anywhere in the United States, but across the Ohio River and north of the Mason-Dixon Line an escaped slave was in relative safety.

Northern Ohio on the Underground Railroad

Ohio was split on the issue of slavery and few communities offered complete safety for runaways, but the town of Oberlin was probably the safest. Located in north central Ohio, Oberlin became one of the major focal points for escaping slaves. Home of Oberlin College, the first school in the United States to admit females and blacks, Oberlin was a key junction on the UGRR with five different routes to safety; it has been referred to as The Town that Started the Civil War.

Oberlin-Wellington Rescue

Two slave catchers and two federal marshals pursued John Price, a 17-year old fugitive slave from Kentucky, to Oberlin on September 13, 1858. Knowing that kidnapping him in Oberlin would not be easy because of anti-slavery sentiments held by the townspeople, they convinced Shakespeare Boynton, son of a wealthy Oberlin landholder, to lead Price to a farm west of Oberlin on the ruse of digging potatoes, for which he would be paid $20.

Instead the lawmen took Price to Wellington, 10 miles south of Oberlin, where they planned to board a train heading south and take Price back to Kentucky and collect a bounty. Realizing what had happened, anti-slavery supporters in Oberlin became outraged and quickly assembled a group to attempt a rescue.

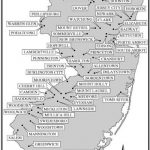

Image: Participants in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue

Courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society

By late afternoon some two hundred people had surrounded the Wadsworth Hotel in Wellington, where Price was being held while they waited for the train. After a standoff of several hours, the captors allowed a small group of men, including the local sheriff, to enter the room to verify their papers were in order. One of the men in the room signaled to the crowd below to place a ladder up to the room’s window.

Soon after, a group of Oberlin citizens climbed in the window and another group came in through the door. Price’s rescuers loaded him into a wagon and took him back to Oberlin. Several days later Price continued on the UGRR to Canada. The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue was influential in raising opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act.

Of the two hundred who had gathered in Wellington, thirty-seven men who helped rescue Price were indicted in Federal Court. They were sent to the Cuyahoga County Jail, where they remained rather than posting bail.

Twelve of these were free blacks, among them Charles Henry Langston, who had helped ensure that Price was taken to Canada rather than released to local authorities. Langston gave a speech in court that was a rousing statement of the case for abolition and for justice for “colored men”. He closed with these words:

But I stand up here to say, that if for doing what I did on that day at Wellington, I am to go to jail six months, and pay a fine of a thousand dollars, according to the Fugitive Slave Law, and such is the protection the laws of this country afford me, I must take upon myself the responsibility of self-protection; and when I come to be claimed by some perjured wretch as his slave, I shall never be taken into slavery…

I stand here to say that I will do all I can, for any man thus seized and help, though the inevitable penalty of six months imprisonment and one thousand dollars fine for each offense hangs over me! We have a common humanity. You would do so; your manhood would require it; and no matter what the laws might be, you would honor yourself for doing it; your friends would honor you for doing it; your children to all generations would honor you for doing it; and every good and honest man would say, you had done right!

The crowd in the courtroom applauded loudly, and continued to do so for some time, in spite of the efforts of the Court to silence it. The judge gave light sentences, assigning Langston to 20 days in jail.

Middle Ohio in the Underground Railroad

Further south, a number of communities provided assistance to runaway slaves including Columbus and Putnam to the east, Mechanicsburg and Urbana to the west. Xenia, Hillsboro and Springfield were also notable communities assisting in this process.

Ohio Anti-Slavery Society

The Ohio Anti-Slavery Society was founded in Zanesville in 1835. The members of the society pledged to fight for the abolition of slavery and to establish laws to protect African Americans after they were freed. Although Ohio was a free state, the Society was constantly under attack from local citizens wherever they held their meetings. John Rankin, one of the founders of the society, was attacked after attending a meeting in Zanesville.

Fear was a primary motivator among those opposing the society’s goals and was often displayed in mobs that physically attacked abolitionists. In 1836, the Ohio Anti-Slavery Convention planned to hold its annual convention in Granville, but the community refused to allow the meeting within the town’s boundaries. When the convention was held in a barn outside the city limits, a mob formed and attacked the abolitionists.

Putnam, Ohio

One of the oldest settlements in the state of Ohio, the town of Putnam was established around 1800, and annexed into the adjacent city of Zanesville in 1872. The town’s residents and institutions played an important role in the Underground Railroad and in Ohio’s debate over the abolition of slavery. Putnam was home to several prominent abolitionists.

Image: Stone Academy in Putnam, Ohio

Station on the Underground Railroad

Stone Academy, built in 1809, is one of the oldest buildings in Putnam. It was the site of two conventions of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society in 1835 and 1839. Noted abolitionist Theodore D. Weld was speaking at the Stone Academy in preparation for the 1835 convention when a mob of anti-abolition residents broke up the meeting.

The Academy, the center of abolitionist activity in Putnam, was attacked again during the 1839 convention, when 200 anti-abolitionists intending to burn all of Putnam were met by 70 Putnam residents at the entrance to their community. Further violence was averted by the arrest of some of the instigators.

The congregation of nearby Putnam Presbyterian Church was actively involved in the abolitionist movement. William Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, served as the first pastor of the church after it was constructed in 1835, and many other anti-slavery speakers spoke here including Frederick Douglas in 1852. A monthly prayer service for the abolition of slavery was held in the church’s basement for many years, a service that was initiated at Stone Academy in 1833.

Southern Ohio in the Underground Railroad

There were twenty-three entry points along the Ohio River, where numerous small communities provided safety for slaves in an extremely dangerous territory. The main entry point was a small community called Ripley. Founded in 1803, Ripley was home to a small group of abolitionists who assisted thousands of escaping slaves and started them on their journey.

Image: Freedom Stairway

Steps that climb almost straight up a cliff from the Ohio River to the John Rankin House.

John Rankin

A Presbyterian minister and educator, John Rankin devoted much of his life to the antislavery movement. His home stood on a three hundred-foot high hill overlooking the Ohio River, and had several secret rooms in which fugitive slaves were hidden. A lantern was placed in a window to indicate that it was safe for fugitive slaves to cross the Ohio River and find shelter at Rankin’s house.

Image: John Rankin House

Ripley, Ohio

John Parker

And another kindred soul who also lived in Ripley, John Parker brought hundreds of fugitives from slavery across the Ohio River in a boat. Born a slave in Norfolk, Virginia, Parker was sold at the age of eight to a doctor in Mobile, Alabama. The doctor’s family taught Parker to read and write and allowed him to apprentice in an iron foundry. At the age of 18, he bought his freedom with money earned from his apprenticeship, moved to Ripley, and established a successful foundry behind his home there.

For generations of slaves in the South, Ohio was the Promised Land. In an interview in later years, John Parker said:

The fugitives, in most instances, have to take care of themselves south of the line, but once across the Ohio River, they were in the hands of their friends.

Not content to wait for laws to change or for slavery to implode, UGRR activists helped fugitives find their way to freedom. Most of the time, however, slaves traveled northward on their own, looking for a signal that meant food, shelter and rest. More than 3200 individuals are known to have worked on the Underground Railroad. Many will remain forever anonymous.

SOURCES

NPS.gov: Putnam Historic District

Ohio History Central: Underground Railroad

Touring Ohio: Underground Railroad in Ohio

Ohio History Central: Ohio Anti-Slavery Society

I also mention the Quaker-Presbyterian village called Mt. Pleasant, Ohio where some residents participated in the Underground Railroad. Ohio was free territory, but before Emancipation, Quakers from Jefferson and Belmont Counties (across the Ohio River from Wheeling, VA., which had a slave market) collected funds ad “bought” slaves, taking them into Ohio and freeing them. These activists favored buying whole families, so as to keep them together as a unit. Despite these abolitionist sentiments in Mt. Pleasant, the village maintained segregated (by race) schools until the 1930s. And even Quaker cemeteries like the one at Concord Meeting House (near Colerain, Ohio) segregated burials by race.