Doctor, Feminist and Social Reformer

Charlotte Denman Lozier, physician, lecturer and professor at the New York Medical College for Women. A feminist, she campaigned for Women’s Suffrage and Workingwomen’s Associations as well as other progressive and charitable organizations.

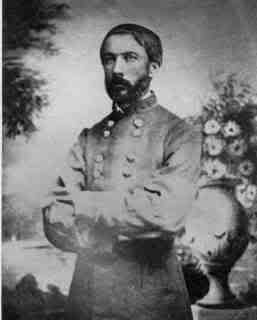

Image: Dr. Charlotte Denman Lozier

Early Years

Charlotte Denman was born March 15, 1844 to Selina and Jacob Denman in Milburn, New Jersey. Eventually a brother and sister were added to the family. Jacob had a strong desire to explore the frontier. When Charlotte was six, the family headed west. The 1850 Census reported them living in Napoleon, Michigan where her brother Robert was born. The family then moved on to Galena, Illinois.

At the time of their next journey to the West, Selina was pregnant again and after several weeks on the trail, she was showing signs of nervous strain as their lifestyle became more strenuous. Charlotte was a great help to her mother during these trying times.

In 1852, they finally reached what is now Winona, Minnesota, where Selina delivered the first white child born on Wabasha Prairie and named her Prairie Louise. There they found the plot of land they wanted, but acquiring it was not easy. After much hasseling and bargaining, Jacob, Selina and the five Denman children laid their claim.

Charlotte loved the frontier. Many times during her life she returned to Winona to be revitalized. Charlotte graduated from high school with high honors. After losing her mother in her teens, Charlotte supported her younger siblings by teaching, but her dream was to become a doctor. In 1864, at age 20 she returned East, hoping to earn a medical degree.

Medical Education

Charlotte enrolled at the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women in New York City, the first medical college for women in the state. This school was founded the previous year by

Dr. Clemence Sophia Harned Lozier, one of the first female doctors in the United States. Dr. Lozier served as President of the College and Chair of the Department of Diseases of Women and Children.

On November 1, 1863, the College opened at 724 Broadway with seven students. The faculty included eight doctors, four men and four women. This was the first institution in New York City where women could study medicine and where women could receive medical care from doctors of their own gender.

At the College, Charlotte met Dr. Abraham Witton Lozier, son of founder. Medicine was a way of life with the Lozier family. Abraham’s grandmother, Hannah Walker Harned, had lived among Native Americans in Virginia for several years, and learned their healing techniques. After a period of independent study, Harned was qualified to act as an attendant to the sick, and she subsequently spent seven years in general practice in New York City. After the family moved to New Jersey, Harned served as the neighborhood medicine woman.

Male students jeered and harassed women students, but Charlotte defied tradition. At that time, most hospitals did not permit women to serve as interns, and thus the only hospital available to women for training was the Hospital for Women associated with New York Medical College. While a student, Charlotte organized a protest against Bellevue Hospital’s refusal to extend clinical privileges to women.

Marriage and Family

Charlotte Denman married Abraham Lozier at Ft. Wayne, Indiana on January 20, 1866, and they spent some time at her family home in Winona, Minnesota before returning to New York. Charlotte earned a degree in medicine in 1867, and she was appointed professor of physiology and hygiene at the New York Medical College in 1868. Charlotte developed a strong interest in women’s rights. Her reputation as an excellent physician opened the way for her lectures concerning women’s rights.

In addition to her medical and suffrage work, Lozier belonged to Sorosis (Sisterhood), an early professional women’s support network. She also served as first vice president of the National Working Women’s Association, an organization that sought improved labor conditions for women of all classes.

Hester Vaughan

During the late 1860s, Dr. Lozier’s passions led her to defend Hester Vaughan, an Englishwoman who came to the United States in 1863 with a man she thought she had married, but he was a bigamist and soon deserted her. Vaughan then took a job as a domestic servant in Philadelphia, where she was impregnated and then abandoned by her employer. She gave birth alone in 1868 in an unheated garret in wintertime. The child died soon after birth.

Hester Vaughan was arrested in 1868 for killing her newborn infant. According to a contemporary Philadelphia newspaper account, the coroner testified that the infant had suffered severe injuries to the skull. A jury found Vaughan guilty of deliberately killing her child, and she was sentenced to be hanged.

Dr. Lozier and other feminists came to Vaughan’s aid. This excerpt from the Wikipedia page about Hester Vaughan (link in Sources below) states that two female doctors visited Vaughan in prison. One of these must have been Dr. Charlotte Denman Lozier, who gave Vaughan free medical care:

Vaughan was visited in prison by a delegation from the WWA that included a female doctor. Another female doctor had also visited Vaughan in prison and had diagnosed her as suffering from puerperal mania, now called postpartum psychosis, which meant that Vaughan was not responsible for her actions at the time she gave birth.

The Revolution, a women’s rights newspaper established by early women’s rights leaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, launched a campaign to win Vaughan’s release from prison. Anthony called for either a new trial for Vaughan or an unconditional pardon on the grounds that she was “condemned on insufficient evidence and with inadequate defense.” Stanton led a delegation to the governor to ask him to pardon Vaughan.

Dr. Charlotte Denman Lozier served as Vice-President of the newly founded Working Women’s Association (WWA) and travelled extensively giving speeches. The WWA decided to come to Vaughan’s defense as its first project. Members organized a large public meeting in New York City, where Dr. Lozier presented exonerating medical and psychological evidence. Anna Elizabeth Dickinson, a famous female orator, also spoke on Vaughan’s behalf.

The WWA also used Vaughan’s situation to highlight several women’s rights issues, stating that economic restrictions were at the heart of women’s sexual vulnerability because it was so difficult for women to find decent and safe work. Members argued that Vaughan was the victim of a social system that sometimes forced women to murder their illegitimate children, and that Vaughan was sentenced to death by a legal system from which women were completely excluded.

Six months later Vaughan was pardoned, and she returned to her native England. The judge later said that infanticide had become so common that some woman must be made an example of.

Career in Medicine

While teaching and maintaining an active medical practice, Charlotte gave birth to two children. Clement Abraham was born November 7, 1866; in May 1868, Robert Ten Eyck was born in May 1868 in Norwalk, Connecticut on the way home from a lecture! By May 1869, Charlotte was pregnant again; she and Abraham hoped for a little girl this time.

Dr. Lozier was praised for defending a young pregnant woman and unborn child against abortion. The patient, Caroline Fuller, had come to Lozier’s office in search of a “termination,” apparently at the urging of her sexual partner, an older married man named Andrew Moran. Lozier counseled against this course of action, while kindly offering her services to help Fuller bear the child.

Moran grew irate and abusive, especially after Lozier refused the large bribe he offered her to carry out his wishes. She sent for a policeman and had Moran arrested. Lozier was criticized for violating privacy. But radical feminists press cheered her for “shielding her sex from the foulest wrong committed against it” and for “coming out firmly to stay the prevalent sin of infanticide.”

This excerpt appeared in an article in The Revolution in 1869:

Dr. Charlotte Lozier… was applied to last week by a man pretending to be from South Carolina, by name, [Andrew] Moran, as he also pretended, to procure an abortion on a very pretty young girl [identified as Caroline Fuller] apparently about eighteen years old. The Dr. assured him that he had come to the wrong place for any such shameful, revolting, unnatural and unlawful purpose. She proffered to the young woman any assistance in her power to render, at the proper time, and cautioned and counseled her against the fearful act which she and her attendant (whom she called her cousin) proposed. The man becoming quite abusive, instead of appreciating and accepting the counsel in the spirit in which it was proffered, Dr. Lozier caused his arrest under the laws of New York for his inhuman proposition.

The Revolution then published extracts from articles in the New York World and Springfield Republican. The latter added that Andrew Moran attempted to bribe Dr. Lozier, “offering to pay roundly [$1000] and shield Mrs. Lozier from any possible legal consequences” should Ms. Fuller die. Lozier refused the bribe. Against critics who claimed Lozier violated medical confidentiality, according to the World:

Dr. Lozier… insists that as the commission of crime is not one of the functions of the medical profession, a person who asks a physician to commit the crime of ante-natal infanticide can no more be considered his patient than one who asks him to poison his wife.

The Revolution editors closed the story with this wish:

May we not hope that the action of Mrs. Lozier in this case is an earnest of what may be the more general practice of physicians if called upon to commit this crime, when women have got a firmer foothold in the medical profession? Some bad women as well as bad men may possibly become doctors, who will do anything for money; but we are sure most women physicians will lend their influence and their aid to shield their sex from the foulest wrong committed against it. It will be a good thing for the community when more women like Mrs. Lozier belong to the profession.

Charlotte was especially busy during the summer of 1869 with the hospital and office duties and running her practice. Summer passed quickly into fall. Christmas and New Year’s were an especially busy and grand time of the year. A party was planned at home for New Year’s Eve. Charlotte had just a few more things to do before her guests arrived. She climbed up a ladder to hang a curtain and became dizzy.

The fall left her on the floor bleeding, and the baby stirred within her as she was rushed to the hospital. This was an unthinkable situation. They were a family of medical doctors, but they could not stem the flow of blood. For four days and nights she lay unconscious; peritonitis finally draining her of life itself.

Dr. Charlotte Denman Lozier died January 3, 1870 died of a hemorrhage at age 25. She was survived by this infant, two older children, and her husband.

Her untimely and widely mourned death was attributed to the urgent need for advances that would not come unless the medical profession and society as a whole became more sensitive to women. Abolitionist and pioneer in women’s health education, Paulina Wright Davis, termed Lozier’s compassion toward Fuller the very action by which “we knew the woman in all her greatness.”

Excerpt from Herald of Health, Volume 15:

In the death of Mrs. Charlotte Denman Lozier, M.D. the world has met with a loss that will not soon be repaired. Although but twenty-four years old, she has lived more and accomplished more than thousands do in three score years and ten… Though thoughtful to a fault of others, she did not sufficiently spare herself, and thus perhaps, weakened her bodily powers so much that she had not strength to go through safely with her confinement.

Should not women who adopt a professional life, and especially the profession of a physician, estimate their own power of endurance, and not go beyond it in their work? Often their lives are a sacrifice for others, as much as a soldier’s life is a sacrifice for his country, but this ought to be less and less the case as hygiene becomes understood.

Dr. Susan McKinney, the first African American female physician in New York State and the third in the nation, graduated from New York Medical College for Women with the highest grade in the class of 1870, the same year of Charlotte’s death.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Hester Vaughan

NYMC.edu: Women in Medicine

Wikipedia: Charlotte Denman Lozier

The Short Life and Times of Charlotte (Denman) Lozier, M.D.

Feminists for Life: Dr. Charlotte Denman Lozier (1844-1870)