Mission to Rescue Slaves in Washington, DC

Pearl was the name of a sixty-five foot Chesapeake Bay Schooner that was chartered by free African Americans for $100 to rescue 77 people from slavery in Washington, DC in 1848. The Pearl Incident was the largest recorded nonviolent escape attempt by slaves in United States history.

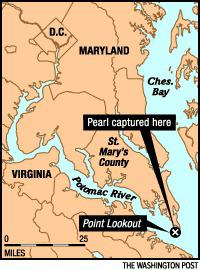

Image: Map of the Voyage

Backstory

Like the nearby states of Maryland and Virginia, Washington, DC had a slave market and was part of the slave trade; because it was connected to the Chesapeake Bay by the Potomac River, slaves were shipped or marched overland through this city. Slaves worked as domestic servants and artisans for their owners, or were hired out to work for others. Free blacks and whites were active in the city, trying to abolish slavery and the slave trade. In 1848 free blacks outnumbered slaves in the District of Columbia by three to one.

The Organizers

Daniel and Mary Bell initiated the planning for the largest slave escape in the history of the United States. Daniel was a free African American blacksmith working at the Navy Yard in the District of Columbia. The Bells had overcome huge obstacles posed by their owners to purchase their own freedom, now they longed to secure freedom for their children and grandchildren.

Since slavery was inherited through the mother, once they purchased Mary’s freedom her entire family were also legally free, and they hoped to avoid their experience of long and bitter negotiations with the owners of their children. But the Bells had run out of money trying to prove their status in court and faced the risk of being captured and sold back into slavery.

The Plan

The escape was organized by both whites and free blacks. The Bells approached William Chaplin, a radical abolitionist who had helped several Washington slaves run away. Chaplin contacted a fellow activist in Philadelphia who recommended Daniel Drayton to organize the escape. Chaplin and abolitionist Gerrit Smith provided the financial backing for the mission and Drayton took care of the details.

A year earlier, Drayton had transported an enslaved family of six from Washington to Philadelphia by boat, for which he had paid 100 dollars to Edward Sayres, the captain of the Pearl, a 54-ton schooner. Sayres’ only crew member was Chester English, a cook. Sayres immediately accepted Drayton’s proposition to follow the same plan, and then brought the schooner to the 7th Street Wharf in Washington.

In coordinating the arrival of the passengers at the appointed time, Drayton worked with two African Americans living in Washington, DC; Samuel Edmonson, who wanted to free his enslaved sisters, and Paul Jennings, a former slave of James and Dolley Madison. Jennings’ role in the Pearl Incident was not discovered at that time; therefore, he was not arrested or imprisoned. Ironically, Jennings provided donations from time to time to the former First Lady, who often lived in poverty as a widow.

When Daniel Drayton arrived in Washington shortly before the voyage, he met with one of his contacts who told him that the plan had changed dramatically. A great many slaves in the District of Columbia and surrounding areas wanted to become part of the escape. Drayton stated that he would welcome anyone who arrived on the boat “before eleven o’clock… the others would have to remain behind.”

The Fugitives

Late in the evening of April 14, 1848, slaves from across the city and surrounding areas slipped away from their places of work and crept through the city, slowly making their way to the wharf. When Drayton and his crew docked at the Wharf, they had no idea how many slaves would be waiting. News of the Pearl had spread like wildfire through the black community, and seventy-six enslaved men, women and children were waiting. Drayton and Sayres accepted the risk of transporting them, and the slaves boarded the ship.

The Voyage

The Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay provided a water route to the free states. The plan was to sail down the Potomac River, and then up the Chesapeake Bay to Philadelphia, where the fugitives could hide from their owners and live in freedom. The voyage would cover approximately 225 miles of water: 100 miles down the Potomac River, then 125 miles north up the Chesapeake Bay.

Image: Replica of the Pearl

The Pearl Coalition will begin to build a replica of the schooner Pearl starting April 2015. When completed, this replica will set sail on the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers.

Casting off in the dark, the Pearl sailed easily down the Potomac, but when they approached the mouth of the river, tides and fierce winds prevented the ship from entering the Chesapeake Bay. The only option was to anchor for the night and try to rest, hoping that any pursuit would be delayed as well.

The Discovery

At daybreak on Sunday, forty-one slave owners in Washington and the surrounding towns awoke to find no blaze in their fireplaces and no breakfast on their tables. Their slaves were gone and they were outraged. Daniel Drayton described the situation in his memoir:

A Mr. Dodge of Georgetown, a wealthy old gentleman, originally from New England, missed three or four slaves from his family, and a small steamboat, of which he was the proprietor, was readily obtained. Thirty-five men, including a son or two of old Dodge, and several of those whose slaves were missing, volunteered to man her; and they set out about Sunday noon.

The Capture

Dodge’s steam boat, the Salem, was sent in pursuit of the Pearl with a posse of 35 armed white men, including local law enforcement officers. Early Monday morning, the posse boat found the Pearl anchored at a sheltered spot near the mouth of the Potomac near Point Lookout in Maryland. Quickly boarding the ship, the captors locked the ship’s hatches, trapping the slaves and their saviors in the hold below.

The slaves must have been terrified listening to the many boots pound the deck above their heads, but they were ready to fight for their freedom. Drayton advised against it; they were greatly outnumbered. Having no other choice, Drayton and the others surrendered, and were towed back up the river to face the consequences of their actions.

The Washington Riot

When the ship and slaves were brought back to Washington, supporters of slavery were outraged by the attempted slave escape, and an angry mob of slave owners formed. The captured freedom seekers and Pearl crew were paraded in chains in Washington, and a slave trader attacked Drayton.

The rioters fixated on Gamaliel Bailey, publisher of The New Era, an antislavery newspaper. Convinced that Bailey had helped plan the mass escape (he had not), the mob threw bricks and stones and broke several windows of the Era’s press offices.

As word of the Pearl Incident spread throughout the city, a mob of slave owners demanded that if editor Bailey did not remove his printing press from the city by 10 a.m. next morning it would be destroyed. The appointed time came and went without further incident.

At the Washington City Jail, a crowd gathered who were determined to drag Drayton, Sayres and English out of the jail and hang them. When Ohio Congressman Joshua Giddings, one of the most vocal antislavery legislators, arrived at the jail to offer legal advice to Drayton and the others, the rioters tried to block his entrance. Undeterred, Giddings continued his visit, and when he left, he stared down the mob and walked away unharmed.

The Washington Riot rocked the nation’s capital; police patrolled the streets for three days and increased protection at key areas around the city. A New York newspaper reporter stated:

There were present a great number of government clerks, who had been requested by the president and the heads of departments as conservators of law and order.

The Punishment

Once the Washington Riot dissipated, the slave owners sold all seventy-six slaves who were involved in the Pearl Incident to slave traders from Georgia and Louisiana, who would take them to the Deep South. There they would likely be sold to work on the large sugar and cotton plantations, where they undoubtedly labored for the remainder of their lives under the unforgiving sun of the South.

The Trial

Both Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres were charged with 77 counts each of aiding the escape – one count or each slave – and transporting the slaves. Cook Chester English was released because he had no knowledge of the Pearl’s cargo or destination. Educator Horace Mann, who had helped the slaves from the La Amistad mutiny, was hired as their attorney.

A jury convicted both Drayton and Sayres, and they were given prison sentences because neither could pay their fines and court costs, a total of about $10,000. After the men had served four years of their prison sentence, abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner petitioned the president for their release. In 1852, President Millard Fillmore pardoned Drayton and Sayres, who were by then widely admired in the black community.

New York Congressman John I. Slingerland alerted anti-slavery activists to the actions of the slaveowners and slavetraders. But by April 21, 1848, slave traders had crowded fifty of the erstwhile fugitives onto rail cars bound for Baltimore, where they would be transported to the Deep South.

A provision of the Compromise of 1850 passed by Congress ended the slave trade in the District of Columbia, but it did not abolish slavery there.

The U.S. Congress passed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act in 1862 and President Abraham Lincoln signed it into law on April 16, 1862, ending slavery in Washington, DC. The 3,100 individuals liberated by this Act were the first slaves freed by federal law. Their owners were the only slaveholders compensated for their loss of property. April 16 is now celebrated in the city as Emancipation Day.

The Betrayal

In 1916, historian John H. Paynter discovered that a slave named Judson Diggs was a driver who had been hired to take two slaves to the Wharf that April night in 1848. They arrived just in time to board the Pearl before it set sail. Diggs became irate when the men had no money to pay him for the ride.

When news spread the following day about the mass slave exodus, Diggs reported what he had observed at the dock that night. Paynter was a descendant of the Edmonson siblings, and had interviewed family members of the other escapees. He wrote:

Judson Diggs, one of their own people, a man who in all reason might have been expected to sympathize with their effort, took upon himself the role of Judas.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Pearl Incident

WETA History Blog: The Pearl Incident

Washington Post: Escape on the Pearl

The Legacy and Significance of a Failed Mass Slave Escape

I have several questions about this post. One specific question is this: What is your source that says that Gerrit Smith funded the Pearl escape attempt?

I’d like to ask the others off blog