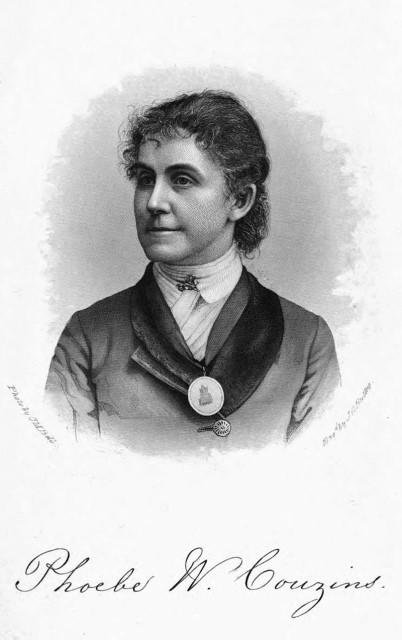

Women’s Suffrage Leader in Missouri

Virginia Minor claimed that as a native-born, free, white citizen of the United States and over the age of 21, the 14th Amendment gave her the right to vote. She attempted to register to vote but was denied because of her gender. Minor filed suit but lost her case – Minor v. Happersett (1874) – in the U.S. Supreme Court. The publicity, however, greatly helped her cause.

Virginia Louisa Minor was born March 27, 1824 in Caroline County, Virginia to Warner and Marie Timberlake Minor. Virginia moved with her family to Charlottesville when her father was appointed hotel keeper at the University of Virginia. Virginia was educated at home and for a short time at an academy for young ladies in Charlottesville.

Marriage and Family

On August 31, 1843, she married her distant cousin Francis Minor, a lawyer and graduate of Princeton and the University of Virginia. They moved to Mississippi, where they lived close to family members who had emigrated there, and in 1844 they joined an even larger family group who had settled in St. Louis, Missouri, where they bought a farm in what is now the Central West End.

Although they came from wealthy southern families, the Minors supported the Union during the Civil War. Minor joined the Ladies’ Union Aid Society, whose members donated supplies, provided financial assistance and served as battlefield nurses. She also assisted in hospitals in the St. Louis area through the Western Sanitary Commission, and provided produce from her farm to Benton Barracks, a Union training facility three miles north of her home, to improve the diet of the soldiers.

After the war ended, many women felt empowered by the public service they had performed and turned their attention to women’s rights. After her only child died in a shooting accident in 1866 at age 14, Virginia Minor launched the women’s suffrage movement in Missouri. She was convinced that women needed the vote for their position in society to improve.

Career in Women’s Suffrage

On May 8, 1867, Minor and four other women founded the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri to “secure the ballot for women upon terms of equality with men.” It was the first organization in the world dedicated solely to winning the right to vote for women. Minor was elected its first president. In February 1869 members of the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri unsuccessfully petitioned the Missouri legislature for the right to vote.

On May 15, 1869, women’s rights leaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton established the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in New York City, in response to a split in the American Equal Rights Assocation over whether the women’s movement should support the 15th Amendment (ratified February 3, 1870) to the United States Constitution, which prohibits federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen’s “race, color or previous condition of servitude.” Anthony and Stanton opposed the Amendment unless it included the vote for women.

The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was formed by Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell and Julia Ward Howe in November 1869. The AWSA founders were staunch abolitionists, and strongly supported securing the right to vote for African Americans. They believed that the Fifteenth Amendment would be in danger of failing to pass in Congress if it included the vote for women.

In October 1869, St. Louis hosted the Missouri Woman Suffrage Convention, the first of its kind held in the state. At the convention, Virginia Minor made an impassioned speech, urging women not to submit to their inferior condition any longer:

I believe the Constitution of the United States gives me every right and privilege to which every other citizen is entitled; for while the Constitution gives the States the right to regulate suffrage, it nowhere gives them power to prevent it.

Francis and Virginia Minor then drafted a set of resolutions which asserted that women already had the right to vote under the U.S. Constitution. Using language from the Fourteenth Amendment, Minor stated that under the terms of the 14th Amendment women were citizens of the United States and entitled to all the benefits and immunities of citizenship. Thus, women already had the right to vote. All they had to do was exercise it.

The Minors then had these resolutions printed in pamphlet form, and circulated them throughout the country. Other general resolutions made by Stanton and the NWSA were included in the pamphlet, which pointed out that women were taxed without representation, governed without their consent, and tried and punished without a jury of their peers.

In advocating for a federal amendment to assure women the ballot, the NWSA relied on the natural rights argument put forth by Virginia Minor, and brought these issues to the attention of the nation by printing Minor’s resolutions in its periodical, The Revolution. At the time of the NWSA’s Washington Convention of 1870, ten thousand copies of Minor’s resolutions were circulating around the audience, with copies placed on the desk of every member of Congress.

Excerpt from the 14th Amendment used by the Minors to make their case:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Attempting to Vote

During the 1872 presidential election, the National Woman Suffrage Association decided to challenge the voting restrictions which excluded women. The nationwide movement originated with Virginia Minor. Frustrated by the lack of legislative action, she saw an opportunity to advance the cause of suffrage for women.

On October 15, 1872, Virginia Minor attempted to register to vote in the upcoming election, claiming that right as a citizen. St. Louis ward registrar Reese Happersett refused to accept her registration because she was a woman. Francis Minor then sued Happersett on his wife’s behalf – married women were not allowed to file lawsuits – arguing she was entitled to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Virginia Minor Case

The Minor’s petition was presented to the court as a written statement on January 2, 1873. Reese Happersett’s lawyer, Smith P. Galt, objected to the Minor’s version of events and appealed to have the case heard during the General Term of the Circuit Court. This hearing took place on February 3, 1873. By agreement, both sides submitted their arguments in writing. There was no trial or jury.

The Minors lost their case in the lower court, but appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, which heard the case in chambers on May 7, 1873. The Court said that the purpose of the 14th Amendment was to extend voting rights to the newly freed slaves, giving African Americans “the right to vote and thus protect themselves against oppression…” and that “There could have been no intention [in the amendment] to abridge the power of the States to limit the right of suffrage to the male inhabitants.” The Minors had lost again.

The case then went to the United States Supreme Court, where it is known as the case of Minor v. Happersett, a landmark Supreme Court decision. Francis Minor made the presentation, claiming that denial of suffrage in the states was a matter of practice rather than law:

The plaintiff has sought by this action for the establishment of a great principle of fundamental right, applicable not only to herself but to the class to which she belongs, for the principles here laid down extend far beyond the limits of the particular suit and embrace the rights of millions of others, who are thus represented through her…. It is impossible that this can be a republican government, in which one-half the citizens thereof are forever disenfranchised.

In October 1874 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone.” The Courts ignored the fact that although women were full citizens under the law, they did not enjoy the same rights as men. The Courts merely upheld the right of individual states to decide which citizens could vote within their borders.

With the Court’s decision, hopes for a judicial solution to the woman suffrage question were dashed. Suffragists then turned their efforts toward state-by-state campaigns to change state constitutions to allow women to vote. These efforts were particularly successful in the West. Thanks to Esther Hobart Morris, Wyoming Territory already allowed women to vote, and Wyoming became a state in 1890 with no voting restrictions placed upon women.

In 1893, Colorado allowed women the vote; in 1896, Idaho, and Utah came into the union in that year with no voting restrictions against women. The State of Washington allowed women to vote in 1910, followed by California in 1911 and Oregon, Arizona and Kansas in 1912. These nine states were the only states to allow woman suffrage before the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

Minor and other members of the suffrage movement continued to fight for the right to vote. In 1879 she became president of the local branch of the NWSA. She testified in support of women’s suffrage before the United States Senate in 1889 to once more state her case. She served as honorary vice president of the Interstate Woman Suffrage Convention, held in Kansas City in 1892.

Virginia Minor died August 14, 1894, and was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis. Since she regarded the clergy as hostile to her goal of equal rights for women, her funeral was conducted without a clergyman. She left $1,000 in her will to Susan B. Anthony for “the thousands she has expended for women,” and $500 to each of two nieces, provided they did not marry; if one married, her share would go to the unmarried niece.

Though Minor did not live to see the passage in 1920 of the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, she inspired women to fight for suffrage through her tenacity and perseverance.

In December 2013, Virginia Minor was announced as an inductee to the Hall of Famous Missourians, where her bronze bust will be one of forty-four on permanent display between the Senate and House chambers in the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City. The busts, which are to be created by Missouri sculptors Sabra Tull Meyer, E. Spencer Schubert and William J. Williams, depict prominent Missourians honored for their achievements and contributions to the state.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Virginia Minor

Distilled History: The Suffragette

Historic Missourians: Virginia Minor

Virginia Minor and Women’s Right to Vote