Businesswoman Who Printed First Bible in America

Jane Aitken (1764–1832) is a significant historical figure in the early nineteenth century. She was one of the first women printers in the early United States and the first woman in the US to print an English translation of the Bible. Aitken was also a publisher, bookbinder, bookseller and businesswoman, a time when the independence of women was actively discouraged. She published at least sixty works from 1802 to 1812.

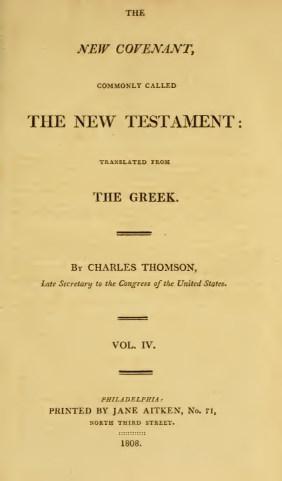

Image: The Thomson Bible, printed by Jane Aitken

Early Years

Jane Aitken was born July 11, 1764 in Paisley, Scotland, the eldest of four children born to Robert and Janet Skeoch Aitken. Her father Robert Aitken was a stationery and book merchant in Scotland as well as a talented printer and bookbinder. The Aitken family emigrated to the American Colonies in 1771 (Jane would have been 7 years old), and settled in Philadelphia, where Robert set up a business selling stationery and books, as well as printing and binding books.

Soon after his arrival in Philadelphia, he established a large and successful bookstore. In 1773, he published Aitken’s General American Register, and the Gentleman’s and Tradesman’s Complete Annual Account Book, and Calendar…for the Year of Our Lord, 1773, which proved his proficiency in the book arts.

The Aitken Bible of 1782

After the American Colonies declared their independence from British rule in 1776, the importation of Bibles was restricted by the British government and the printing of Bibles in the colonies was forbidden. Therefore, by 1777 there was a severe shortage of Bibles in America.

On January 21, 1781, Robert Aitken petitioned Congress for permission to print a complete Bible for the American people. Aitken’s impressive credentials – which included publishing the Journals of Congress and publishing numerous articles by Thomas Paine – convinced the committee, and on September 10, 1782, Aitken was give permission and financial support to print the first edition of the first American Bible.

George Washington, one of the greatest supporters of the Aitken Bible, was so pleased with the result that he regretted that the Revolutionary troops had been disbanded before he could provide them each with a copy of the Aitken Bible. Writing to a friend, Washington lamented, “It would have pleased me well… to make such an important present to the brave fellows who have done so much for the security of their Country’s rights and establishment.”

The printing of the new Bible marked a significant moment in the history of the United States. The Aitken Bible was championed by the people and symbolized a dramatic release from British control over their right and ability to worship. In 1789, Aitken appealed to Congress for a patent for the exclusive right to print Bibles in America for fourteen years. It was denied. By that time, other American printers were publishing Testaments.

The sad picture of Robert Aitken’s financial status a decade after his first memorial to Congress can be glimpsed in a communication he sent in 1791 to John Nicholson, at that time Receiver of general taxes for the state of Pennsylvania:

I have calculated from my true loss by Continental money 3,000 and on the Edition of 10,000 Bibles 4000 – owing to these you may readily figure my situation. My house is under mortgage for a considerable sum, a foreign debt, though not of its value. I have other debts to pay, not considerable–what I earn goes to pay them as soon as earned…

As she grew older, Jane Aitken became more and more involved in her father’s business. Her handwritten bookkeeping entries show that the shop printed a newspaper, journals, books and stationery. The business gained an excellent reputation from the printing of the Aitken Bible of 1782, the first English Bible printed in the colonies.

Despite Robert Aitken’s hard work, when he died in 1802 he left a debt of $3000, an enormous amount for the time. The debt was largely incurred by Jane’s late brother-in-law Charles Campbell, a clock and watchmaker who struggled to make his business a success, and for whom her father had signed a number of notes.

Career in Printing and Bookbinding

Robert Aitken Jr., who was a year younger than Jane, had been disowned by their father. Therefore, Jane inherited the printing and bookbinding business from her father’s estate when she was thirty-eight years of age. As the oldest child, she also assumed the responsibility of caring for her two younger sisters, one recently widowed with three children. Probably because of all these familial responsibilities, Jane never married.

As the oldest and the second most experienced printer in the Aitken family, Jane might have decided to remain unmarried in order to better assist her father with the printing business. At any rate, Jane spent the entirety of her adult life struggling to contend with her father’s legacy: a solid reputation for printing and an enormous debt. There are conflicting accounts as to whether that debt was ever paid.

The publications were thereafter in her own name as Printed by Jane Aitken from her printing business, which she ran on Third Street in Philadelphia. Based on the similarity and continuity of bookbinding and printing styles sustained long after her father’s death, Jane Aitken must have learned the printing and bookbinding trades at an early age, and had been performing those tasks for many years.

Like her father, Jane Aitken was an extremely talented and prolific printer and bookbinder. She was responsible for printing a number of publications after she took over the business, including contracts from the Female Association of Philadelphia for the Relief of Women and Children in Reduced Circumstances – founded by philanthropist Rebecca Gratz in 1801; the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, and some 400 volumes for the American Philosophical Society.

Aitken had a difficult time financially and mostly depended on the bookbinding for subsistence. She bound many of the author’s books she printed up, and her binding output in the later years is very similar to that from her father’s shop, suggesting she may have been doing the binding all along. One source says that she is “the only woman binder of such skill known to us from this period.”

The Aitken Bible of 1808

Jane Aitken produced at least sixty publications between 1802 and 1812. Like her father, she undertook an ambitious Bible project called the Thomson Bible, the first English Bible printed by a woman in the United States. The four-volume Bible printed in 1808 was, like her father’s before her, well-received for its craftsmanship but a commercial failure.

This Bible, prepared by former secretary of the Continental Congress Charles Thomson, was the first English translation from the Septuagint (the Greek version of the Hebrew Scriptures or Old Testament). According to the contemporary printing historian Isaiah Thomas, this work firmly established Aitken’s reputation for excellence. But, like her father, Jane fell into debt.

The American Philosophical Society’s Librarian and wealthy merchant John Vaughan is described as a tireless supporter of Miss Aitken. Little is known of their relationship, but it appears that he served as her investor and benefactor when she fell on hard times. After her printing equipment was seized and sold at a Sheriff’s sale for nonpayment of her debts in 1813, Vaughan bought most of her equipment and leased it back to her.

In spite of continuous printing work, Aitken sometimes had to rely on bookbinding to earn a living. The similarity of her known bindings from later years to those issued from her father’s shop from the 1780s to 1802 raises the possibility that she was responsible for much of the bindery output during those years. The quality of her bindings qualifies Aitken as a distinguished bookbinder; in fact, the only known woman bookbinder with such skill from this period.

Late Years

Aitken’s great skill, hard work, and even Vaughan’s generosity were not enough to overcome the burden of her inherited debts. In 1814 Jane served time for nonpayment of her debts in a Norristown, Pennsylvania prison. While it is uncertain exactly how long the prison term lasted, Aitken is recorded as doing binding work in 1815. The next record of her is in the 1819 city directory, which lists her as the “late printer.”

It is difficult to determine exactly when and why her business career ended, but her reputation as one of the finest publishers and binders of this period lives on, as does her achievement as the first woman printer of the Bible in America.

Jane Aitken died August 29, 1832 at the age of sixty-eight, and her obituary in the Germantown Telegraph reported that she had died after a “long and painful illness.” Her burial place is assumed to be in the destroyed cemetery of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, of which she was a member.

SOURCES

Jane Aitken Papers

Wikipedia: Jane Aitken

Wikipedia: Robert Aitken

The Bible of the American Revolution