Doctor and Pioneer in Women’s Education

Clemence Sophia Harned Lozier was one of the first women doctors in the United States. In 1863 she founded the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women, the first school where women of New York City could study medicine and the first hospital where women patients could receive medical care from doctors of their own gender.

Image: Dr. Clemence Sophia Harned Lozier

Early Years

Dr. Clemence Sophia Harned was born December 11, 1813, in Plainfield, New Jersey, and educated in the Plainfield Academy. She was the youngest of 13 children born to David and Hannah Walker Harned, who had lived among the Native Americans in Virginia for several years before moving to New Jersey.

Hannah had learned Native American healing techniques, and after a period of independent study, she was qualified to act as an attendant to the sick. Harned subsequently spent seven years in New York City in general practice with the advice of her cousin, Dr. Carroll Dunham. After the family moved to New Jersey, she served as the neighborhood ‘medicine woman.’

Growing up, Lozier watched her mother’s capable hands heal time and time again, which was the beginning of her interest in medicine. By this time, two of her older brothers had left home and were in training to become doctors, just as Lozier hoped to do. Unfortunately, both of her parents died when she was 11, and she was sent to live and study at the local Plainfield Academy.

At age seventeen she left school to marry Abraham Witton Lozier, an architect by profession, who built for her a home on Tenth Street in New York City, where they lived until 1837. Lozier gave birth to seven children, but only one, Abraham Witton Lozier, Jr. survived childhood.

School for Girls

A few years later, Lozier’s husband fell ill and was unable to work. Forced to support her family, Lozier opened a girls’ school in her home in 1832, and soon established herself as a highly-regarded teacher, enrolling girls from some of New York City’s most prominent families. She taught an average of 60 students a year for the next decade.

During this period Lozier studied medicine under the direction of her brother, Dr. William Harned. Lozier had always been interested in anatomy and hygiene and she stunned conservatives by teaching these subjects, which were considered inappropriate for young women at that time.

Around this time, Lozier also got involved with reform work, particularly with the New York Moral Reform Society, whose mission was to steer women away from prostitution and to reform those who had fallen into it. Highly religious, Lozier edited the Moral Reform Gazette and held weekly gatherings to “promote holiness.”

Lozier’s husband died in 1837, and although she was 24 at the time, she continued her informal medical studies with her brother. About 1844, she moved to Albany and married John Baker, who turned out to be an alcoholic. The burden of a drunken husband proved too much for her, and in 1861 she applied for and received a divorce – not an easy thing in those days – and once again took the name Lozier.

She credited her ability to survive these hard times, in part, to Elizabeth Cady Stanton who offered encouragement and support. Dr. Lozier corresponded with Stanton and recalls:

[A]t a period when I was in the depths of despair, crippled in every effort for self-support and self-development by an unworthy husband, [Stanton’s] letter came to me like a clarion call, to rise up, sunder such unholy ties, and walk forth to freedom. It filled me with the courage to do what I had long seen to be my duty.”

Pursuing a Medical Degree

Learning that Elizabeth Blackwell, after great difficulties, had graduated in 1849 from the Geneva Medical College in Geneva, New York, Lozier decided to enroll there as well. The school apparently did not want to repeat the experience; they refused to admit any more women. Lozier knew she would have to fight to be admitted to a medical school.

More determined than ever to earn a medical degree, Lozier abandoned her profession of teaching. In 1847 the Medical School of Fredonia, New York moved to Rochester, New York and was named the Eclectic Medical Institute of New York, where Lozier persuaded officials to allow her to attend a course of medical lectures.

In 1849 the Eclectic Medical Institute merged with Randolph Eclectic Medical Institute and moved to Syracuse to become the Central Medical College of New York, which agreed to admit Lozier as a medical student. In 1850 the Central Medical College of New York moved to Rochester and became Rochester Eclectic Medical College.

In 1852 the school again moved to Syracuse and took the name Syracuse Medical College, which was in existence until 1855. There Lozier graduated with high honors in March 1853 at the age of 40, and then returned to her New York City home. In an age when there were virtually no medically-trained women doctors, Lozier launched her practice, specializing in obstetrics and surgery.

The timing of Lozier’s advent into the medical profession only added to the success of her practice. At that time, obstetricains were just beginning to use anesthetics and surgical techniques during delivery. Her practice grew rapidly not only because of her abilities but because there were so few well trained women doctors. She was very successful financially, and attained annual incomes of up to $25,000.

New York Medical College for Women

In 1860, Lozier began offering a series of lectures in her home about anatomy, physiology and hygiene because these subjects were rarely offered to females. Not only were women considered intellectually inferior to men, females were thought to be too squeamish for medical courses. Lozier organized her own medical library so she could offer advanced study to these curious women.

The lectures from the beginning were instructive and interesting, and were especially intended to furnish physical, mental and moral training to women for the functions of maternal and child care. Her weekly health classes quickly became very popular, causing Lozier to realize that women wanted and needed more knowledge in these areas.

From these crowded lectures came the idea of a medical college for women. In the spring of 1863, Dr. Clemence Lozier and her associates, particularly Elizabeth Cady Stanton [link], petitioned the New York Legislature in order to establish a medical college for women in New York City.

On April 14, 1863, after a long struggle, the state legislature granted a charter for a medical college for women, the first in the state. On November 1, 1863, the New York Medical College for Women opened at 724 Broadway with seven students. The faculty included eight doctors, four men and four women. Dr. Lozier was President of the College and the Chair of the Department of Diseases of Women and Children.

The struggle, however, was far from over. According to the charter, Lozier’s students were given the right to attend clinics at Bellevue Hospital in conjunction with their studies at the medical school. However, the male students and professors there made it clear they were not welcome, greeting them with hisses and jeers. At one point, the women required police escorts to attend clinics.

Emily Schettler was the first graduate in 1864. Henry Ward Beecher, Lucretia Mott [link] and Elizabeth Cady Stanton each delivered commencement speeches at the colleges’ first graduation. Also in 1864, the legislature amended the original act to include a hospital with the college, and the institution became known as the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women.

In 1867, Dr. Lozier traveled to Europe to study medical practices there. When she returned, she established a new curriculum and reorganized the faculty. Lozier became Dean of the college and professor of obstetrics and gynecology. In June 1868, she purchased a property for both the college and the hospital at Second Avenue and 12th Street.

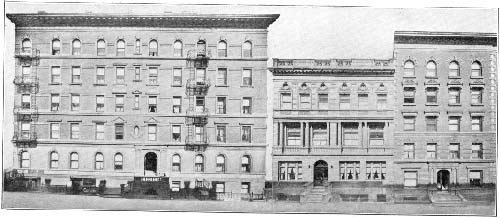

Image: New York Medical College and Hospital for Women

Second Avenue and 12th Street, New York City

From left to right, newly acquired building, old hospital and rented nurses home.

Dr. Lozier donated large sums of her own money to the college over the years and never accepted a salary during her many years of service. Though women were accepted at Lozier’s school, they could not become members of the American Medical Association, even after earning their degrees. The AMA, founded in 1846, did not accept female members until 1915.

During the next 25 years, while Dr. Lozier was President and Dean, the College and Hospital grew from its humble beginnings of 7 students to 219 women who received medical degrees and went into practice from Maine to California. Prejudice had been somewhat overcome. No longer did men students hiss and jeer as visiting women students came to amphitheaters for clinical instruction.

The school’s hospital was run by Lozier’s students and graduates who cared for about 200 patients annually. The school’s clinics, however, served about 2,000 patients per year, highly popular because it was about the only place in the city where female patients could be treated by female doctors.

Over the years, Lozier also published a few medical texts, and occasionally contributed to medical journals. Her most noted work was an 1870 pamphlet entitled Child-Birth Made Easy.

Women’s Suffrage Movement

Dr. Lozier provided generous financial support ($50 per week, quite a sum back then) to Anthony’s suffrage publication Revolution when the paper needed it. Aside from Anthony, Stanton and other noted reformers, Wendell Phillips, Hamilton Wilcox and Gerritt Smith often attended Lozier’s parlor meetings.

Lozier’s home was also a meeting place for advocates of women’s causes. She counted Susan B. Anthony [link] among her friends and visitors. When Anthony had trouble finding enough money to publish her weekly paper The Revolution, Lozier made a donation. Active in the women’s suffrage movement, Lozier was president of the New York City Woman Suffrage Society from 1873 to 1886.

A highly successful doctor, Lozier used her earnings to support the women’s suffrage movement. A social reformer, she held monthly meetings of the anti-slavery society at her home, and as secretary of the Female Guardian Society, she visited New York prisons and slums to rescue and/or give charity to destitute women and children. And her home became a storehouse for various pamphlets touting other causes of the day.

For a number of years Dr. Lozier had suffered from angina pectoris (chest pain caused by obstruction or spasm of the coronary arteries). On April 24, 1888, she delivered the main address at her medical school’s 25th commencement ceremony. She worked on April 26, saw friends and patients, but that evening complained of pain and fatigue. Lozier later called her maid and told her she feared an attack of angina was coming on. She died later that night.

Dr. Clemence Sophia Lozier died of angina pectoris April 26, 1888, at the age of 76 in her home, 103 West 48th Street, New York City. She was buried at the Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Excerpt from King’s History of Homeopathy:

An incident connected with her funeral, worthy of note, is that six women physicians, niece, grandnieces and cousin, all descendants of her brothers, followed her remains into the church. Fortyeight women physicians, graduates of the college which she founded, passed her coffin and took their last look at her sweet face, and dropped into the casket a sprig of arbor vitae as their tribute of love.

Dr. Lozier did not neglect her home life, nor sacrifice it to her professional career. All of her children died in early infancy except her seventh and last son, Dr. Abraham Witton Lozier Jr. He wrote this about his mother:

Perhaps no woman of her age has accomplished so much in so many different directions for women. No one ever inspired women more with faith in themselves, nor ever a readier hand worked with a readier heart for mankind.

The New York Medical College and Hospital for Women closed in 1918 when it was absorbed by the New York Medical College and Fifth Avenue Hospital. Lozier’s portrait, however, was placed at the affiliated school. In 1920, women earned the right to vote, some 50 years after Lozier first took up the cause.

Lozier’s granddaughter, Jessica Lozier Payne, public speaker and commentator on current events, wrote:

I was eighteen years old when my grandmother, Dr. Clemence S. Lozier, died. My strongest recollection of her is her gracious personality and gentle beauty, with soft curls framing her face. Although forceful in character, she gained results by persuasion and example. Many and difficult were her problems, but sustained and inspired by her active faith, she solved them, and won a prominent place in the medical profession…

SOURCES

Dr. Clemence Sophia Harned Lozier

Gale Encyclopedia of Biography: Clemence Sophia Harned Lozier

History of the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women