First Woman to Preside Over a Public Meeting

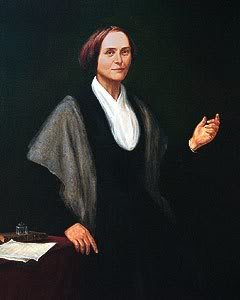

Abigail Norton Bush was an abolitionist and women’s rights activist who served as president of the second women’s rights convention in Rochester, New York in 1848 immediately following the Seneca Falls Convention, and thus became the first American woman to serve as president of a women’s rights convention.

Early life

Abigail Norton Bush was born in Cambridge, Washington County, New York on March 19, 1810. When she was very young, her family moved to the upstate New York town of Rochester in upstate New York, which was the home of many early social reformers in the early and mid 1800s. In the 1830s, Bush worked for the Rochester Female Charitable Society, an organization devoted to the care of the poor and the ill.

Marriage and Family

In 1833 Abigail Norton married stove manufacturer Henry Bush. Over the next thirteen years, Abigail Bush went through childbirth six times between 1834 and 1846 (two children died in infancy). The family often struggled financially. The Bushes were ardent supporters of the abolitionist movement, and their home became a station on the Underground Railroad.

In a split among abolitionists in 1840, Henry Bush chose to remain with the American Anti-Slavery Society, while Abigail Bush grew more sympathetic to radical reform, and became active in the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society.

Rochester Women’s Rights Convention

The first women’s rights convention was held at Seneca Falls, New York on July 19 and 20, 1848, under the leadership of Elizabeth Cady Stanton [link] and Lucretia Mott. The women attending that convention were urged to hold similar meetings in their own cities.

Bush was not at Seneca Falls, but the representatives from Rochester who did attend were moved to organize a convention of their own. Before leaving Seneca Falls, they convinced Lucretia Mott [link] to stay in New York long enough to be the featured speaker at their convention, as she had been at Seneca Falls.

Back in Rochester an Arrangements Committee met to organize the convention. A nominating committee composed of Amy Post, Rhoda DeGarmo and Sarah Fish met on the evening of August 1, 1848 to select officers for the convention.

On August 2, 1848 – twelve days after Seneca Falls – the second women’s rights convention was held at the Unitarian church in Rochester. Amy Post called the meeting to order and reported on behalf of the committee the following persons to serve as officers: Abigail Bush, president; Laura Murray, vice president; Catharine A. F. Stebbins, Sarah L. Hallowell and Mary H. Hallowell, secretaries.

Women serving as officers? This radical departure from the norm created much controversy – men always presided over public meetings. Bush later recalled that those who opposed her stopped her in the hall, and tried to persuade her to give up her position as president. According to Bush, the group said that James Mott (husband of Lucretia Mott) would be happy to serve in her place. She refused their offer.

Even the most committed feminists were strongly against the idea of a woman president. They did not want to give a bad public image to the new women’s rights movement. Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked how could a woman serve as president without any knowledge of parliamentary procedure and no experience in holding public meetings?

Post, De Garmo and Fish convinced Bush to proceed, but when Bush took her position as president, Mott and Stanton left their places of honor on the platform and took seats in the audience. One of the secretaries then read the minutes of the previous convention at Seneca Falls.

Cries of “louder, louder” were heard from audience members who could not understand the soft- spoken words of the secretary. Abigail Bush took the platform and said:

Friends, we present ourselves here before you, as an oppressed class, with trembling frames and faltering tongues, and we do not expect to be able to speak so as to be heard by all at first, but we trust we shall have the sympathy of the audience, and that you will bear with our weakness now in the infancy of the movement. Our trust in the omnipotency of right is our only faith that we shall succeed.

Bush went on to perform her duties through all three sessions of the convention, becoming the first woman to preside over a public meeting attended by a mixed audience of men and women.

After a speech by Frederick Douglass [link] a young newlywed, Rebecca Sanford, came forward and asked to say a few words. She was on her way west, but she had taken a later train in order to make one of the most inspiring speeches given at the Rochester convention. Her new husband stood near her while she spoke. This is an excerpt:

… I do not intend to speak of oppressive and tyrannical power as woman’s right, but that if you will galvanize her into civil liberty, you will find her capable of being in it, and of sustaining it. Place her in equal power, and you will find her capable of not abusing it! Give her the elective franchise, and there will be an unseen, yet a deep and universal movement of the people to elect into office only those who are pure in intention and honest in sentiment!

Give her the privilege to cooperate in making the laws she submits to, and there will be harmony without severity, and justice without oppression. Make her, if married, a living being in the eye of the law – she will not assume beyond duty; give her right of property, and you may justly tax her patrimony as the result of her wages. Open to her your colleges – your legislative, your municipal, your domestic laws may be purified and ennobled. Forbid her not, and she will use moderation…

Late that evening, Bush adjourned the meeting “with hearts overflowing with gratitude.” Lucretia Mott hugged Bush warmly, thanking her for presiding. Stanton apologized for her own “foolish conduct” in doubting Bush’s ability to succeed.

From that point forward, women were always chosen president of women’s rights conventions in the United States. However, after the convention had ended, Bush became emotional and said later that, “When I found that my labors were finished, my strength seemed to leave me and I cried like a baby.”

In late December 1848, Abigail Bush was a member of the business committee of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society. Her contribution, and that of two other Rochester women, fulfilled the Society’s tenet of equal social participation of women.

Moved to California

In 1849 or 1850, after years of suffering business losses, Henry Bush headed west to join the California Gold Rush and to make a life there. He left a pregnant Abigail in Rochester. By the early 1850s, the whole family had settled in California, where Bush was to live for the rest of her life.

In 1878, she sent a congratulatory letter to the National Woman Suffrage Association, which was then holding a convention in Rochester to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls and the second at Rochester. She wrote, “Say to your convention my full heart is with them in all their deliberations and counsels, and I trust great good to women will come of their efforts.”

When Frederick Douglass passed through Rochester during his escape from slavery the Bush family helped him. In 1883, some forty years later, Abigail Bush wrote Frederick Douglass to find out if he remembered her and asked for his photograph. The local newspaper, the Contra Costa Gazette, reported as follows:

The answer came with a promptness that at once evidenced his recollection of a regard for the writer. He expresses his great pleasure to hear from one who had befriended him in days when friends were scarce… He speaks of his present position and future plans as he would to his most trusted friend, and in lieu of a photograph sends [a] cleverly executed pencil picture of himself, together with a copy of his address on the 21st anniversary of slavery Emancipation. Mrs. Bush feels justly proud of these treasures which it is needless to say will be carefully preserved.

Fiftieth Anniversary Convention

In 1898, at the National American Woman Suffrage Association 50th anniversary convention, Abigail Bush and other founders of the movement were honored at a Pioneer’s Evening. Still living in California, she sent a letter to Susan B. Anthony, in which she reminisced about her role in the 1848 Rochester convention:

To Susan B. Anthony, Greetings

You will bear me witness that the state of society is very different from what it was fifty years ago when I presided at the woman’s Rights Convention. I had not been able to meet in council at all with the friends, on account of sickness in my family untill I met them in the hall as the congregation were gathering and then fell into the hands of those who urged me to take part with the supporters of a woman serving as the president of the meeting.They had James Mott, a fine-looking man, to preside at Seneca Falls, but his head fell at the hands of my old friends Amy Post, Rhoda DeGarmo and Sarah Fish, who at once commenced laboring with me to prove the hour had come when a woman could preside and led me into the church. Amy proposed my name as president. It was accepted at once, and from that hour I seemed endowed as from on high…

On my taking the chair Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton left the platform and took seats in the audience, but this did not move me from performing all of my duties; and at the close of the first session Lucretia Mott came forward, folded me tenderly in her arms and thanked me for presiding. The Unitarian Church was open for us. I do not suppose another church in the city would have been. When I found that my labors were finished, my strength seemed to leave me and I cried like a baby. But that ended the feeling with women that they must have a man to preside at their meetings.

From that day to this, in all the walks of like, I have been faithful in asserting that there should be no taxation without representation. It has seemed a long day in coming, but I think it draws nearer and that woman will be acknowledged as an equal with man. Heaven grant the day may come soon!

With kind love to all the workers.

Affectionately, Abigail Bush

88 years old

But neither she nor Susan B. Anthony would live to see what they started come to a triumphant conclusion in 1911 in California and nationally in 1920.

Abigail Bush died at Vacaville, California on December 10, 1898 at the age of 88. She is buried with her husband in Alhambra Pioneer Cemetery on a hill across the city from the one on which she had lived for nearly 30 years.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Abigail Bush

Martinez Historical Society: Abigail Bush

Western New York Suffragists: Abigail Norton Bush

Upstate New York and the Women’s Rights Movement