Washington Irving’s One and Only Love

Though she died very young, Matilda Hoffman made such a deep impression on the young American author Washington Irving (The Legend of Sleepy Hollow) that he mourned her passing for the rest of his life. Decades later, the mere mention of her name left him speechless.

Sarah Matilda Hoffman was born in 1791, daughter of Josiah Ogden and Mary Colden Hoffman. Matilda, as she was known, grew up in Manhattan and Albany, New York. Her mother died when she was six years old and her father married Maria Fenno five years later and began a second family. Maria was only ten years older than Matilda.

Josiah Ogden Hoffman served as New York Attorney General from 1795 to 1802, and then returned to private practice in Manhattan. From 1802 until 1804 Hoffman trained a law student named Washington Irving whose family had come to America from the Orkney Islands and Cornwall. Irving had spent much of his life surrounded by descendants of the original Dutch settlers of New York, including the very distinguished Hoffman family.

Irving, eight years older than Matilda, was a mediocre student, barely passed the bar in 1806, and did not seem particularly interested in practicing law. His first love was writing, and he had already achieved some notoriety as a teenager with some amusing commentaries on Manhattan society.

In 1804 Hoffman decided to send Matilda to boarding school in Philadelphia and asked his new wife’s best friend, Jewish philanthropist and educator Rebecca Gratz [link], to look after Matilda while she was there. Rebecca, who had previously met Matilda, gladly accepted the responsibility. She also suggested that Matilda stay at the Gratz house for a time before starting school to “give her an opportunity of becoming acquainted with my family as I wish her to look upon us as friends and our house as a home.”

During the school terms for the next sixteen months, Rebecca Gratz’s letters to Maria are full of news about the clothes and shoes she has purchased for Matilda, outings they’ve been on and weekends spent at the Gratz house. In the spring of 1806, Maria wrote that Rebecca must bring Matilda home because one of her favorites, Washington Irving, was just back from Europe.

While apprenticing in Judge Hoffman’s law office, Irving had been a frequent visitor at the Hoffman home, and he again became a familiar presence in the household, playing the role of the “fun” older brother to the siblings. His new friendship with Rebecca and her family would grow through visits in Philadelphia and New York.

By the autumn of 1808, it had become common knowledge that Washington Irving had fallen in love with Matilda Hoffman. Judge Hoffman, who liked Irving very much and thought that Matilda was mature enough to think about marriage, offered his consent – but only if Irving could provide some financial security for his daughter.

Now that he was engaged to Matilda, Irving tried to dedicate himself to the law, but his heart was not in it. The two wanted desperately to get married but Irving still did not have a reliable source of income. He and some friends started a magazine, Salmagundi, which is mostly remembered for the nickname he coined for the city of New York: Gotham. However, the magazine did not generate enough money to support a family.

At the same time, Irving, now twenty-five years old, was writing his first book, A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty. During that time Irving wrote about Matilda:

We saw each other every day, and I became excessively attached to her. Her shyness wore off by degrees. The more I saw of her the more I had reason to admire her. Her mind seemed to unfold leaf by leaf, and every time to discover new sweetness. Nobody knew her so well as I, for she was generally timid and silent; but I in a manner studied her excellence.

Never did I meet with more intuitive rectitude of mind, more native delicacy, more exquisite propriety in word, thought and action, than in this young creature. I am not exaggerating; what I say was acknowledged by all who knew her. Her brilliant little sister used to say that people began by admiring her, but ended by loving Matilda. For my part, I idolized her. I felt at times rebuked by her superior delicacy and purity, and as if I was a coarse, unworthy being in comparison.

All the while Irving was working feverishly on his book, hoping that publishing it would generate some income and he could finally marry his sweet Matilda. In February 1809 Matilda came down with a cold which quickly worsened.

In the mean time I saw Matilda every day, and that helped to distract me. In the midst of this struggle and anxiety she was taken ill with a cold. Nothing was thought of it at first; but she grew rapidly worse, and fell into a consumption [tuberculosis]. I cannot tell you what I suffered. The ills that I have undergone in this life have been dealt out to me drop by drop, and I have tasted all their bitterness. I saw her fade rapidly away; beautiful, and more beautiful, and more angelical to the last. I was often by her bedside; and in her wandering state of mind she would talk to me with a sweet, natural, and affecting eloquence, that was overpowering.

I saw more of the beauty of her mind in that delirious state than I had ever known before. Her malady was rapid in its career, and hurried her off in two months. Her dying struggles were painful and protracted. For three days and nights I did not leave the house, and scarcely slept. I was by her when she died; all the family were assembled round her, some praying, others weeping, for she was adored by them all. I was the last one she looked upon. I have told you as briefly as I could what, if I were to tell with all the incidents and feelings that accompanied it, would fill volumes…

Matilda Hoffmann died of consumption on April 26, 1809 at the age of 17.

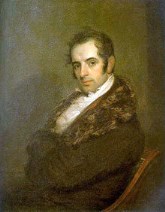

Image: Portrait of Washington Irving

Painted by John Wesley Jarvis in 1809, the year of Matilda’s death

On December 6, 1809, Washington Irving published his book, A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, to immediate critical and popular success. This was a satirical history of the city written from the point of view of an eccentric old Dutch professor named Diedrich Knickerbocker.

Irving promoted the book by claiming that Knickerbocker was a real person and that he had left the manuscript at the front desk of Irving’s hotel before disappearing without a trace. The book became so popular among New Yorkers that they began calling themselves Knickerbockers.

Washington Irving rarely mentioned Matilda afterwards, but he wrote in a letter to a friend years later:

I cannot tell you what a horrid state of mind I was in for a long time. I seemed to care for nothing; the world was a blank to me. I abandoned all thoughts of the law. I went into the country, but could not bear solitude, yet could not endure society. There was a dismal horror continually in my mind, that made me fear to be alone. I had often to get up in the night, and seek the bedroom of my brother, as if the having a human being by me would relieve me from the frightful gloom of my own thoughts.

Months elapsed before my mind would resume any tone; but the despondency I had suffered for a long time in the course of this attachment, and the anguish that attended its catastrophe, seemed to give a turn to my whole character, and throw some clouds into my disposition, which have ever since hung about it. When I became more calm and collected, I applied myself, by way of occupation, to the finishing of my work. I brought it to a close, as well as I could, and published it; but the time and circumstances in which it was produced rendered me always unable to look upon it with satisfaction.

Still it took with the public, and gave me celebrity, as an original work was something remarkable and uncommon in America. I was noticed, caressed, and, for a time, elevated by the popularity I had gained. I found myself uncomfortable in my feelings in New York, and traveled about a little. Wherever I went, I was overwhelmed with attentions; I was full of youth and animation, far different from the being I now am, and I was quite flushed with this early taste of public favor.

Still, however, the career of gayety and notoriety soon palled on me. I seemed to drift about without aim or object, at the mercy of every breeze; my heart wanted anchorage. I was naturally susceptible, and tried to form other attachments, but my heart would not hold on; it would continually recur to what it had lost; and whenever there was a pause in the hurry of novelty and excitement, I would sink into dismal dejection. For years I could not talk on the subject of this hopeless regret; I could not even mention her name; but her image was continually before me, and I dreamt of her incessantly.

Irving had been living comfortably through the ensuing years, in part because of money he received from his father, but in 1818 the family business went bankrupt, and suddenly Irving had to support himself. Knowing that he would now have to make a living from his writing, he studied popular tastes and learned to soften his satire and employ milder forms of romanticism, such as sentimentalism.

He went to work on what would become his most famous book, a collection of 34 essays and short stories entitled The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon (1819). Most of the pieces in it were descriptions of England, where he had spent a good deal of time since Matilda’s death. It also contained Americanized versions of European folktales.

Two of the stories were rewritten German folktales which he transplanted in American soil. The first of these was Rip Van Winkle, the tale of a man who falls asleep during the British rule of the American Colonies, only to wake up years later to find himself in the newly created United States of America. The story is set in New York’s Catskill Mountains, but Irving later admitted, “When I wrote the story, I had never been on the Catskills.”

In another of these stories, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Irving invented one of the most memorable characters in American literature, the visiting schoolteacher Ichabod Crane, whom Irving described as:

tall, but exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and legs, hands that dangled a mile out of his sleeves, feet that might have served for shovels, and his whole frame most loosely hung together… To see him striding along the profile of a hill on a windy day, with his clothes bagging and fluttering about him, one might have mistaken him for… some scarecrow eloped from a corn-field.

Both Rip Van Winkle (1819) and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow were revolutionary American short stories because they suggested that the fledgling nation actually had a history. When Sleepy Hollow was published, there were no internationally known American fiction writers.

Washington Irving never married. He spent the last twenty-four years of his life in Tarrytown, New York, where he purchased his famous home, known as Sunnyside, in 1835. He continued to write, even after his popularity had declined.

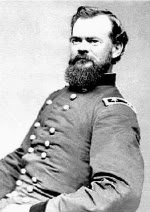

Image: Sunnyside, home of Washington Irving

On the Hudson River in Tarrytown, New York

Originally a Dutch farmer’s house, it has been meticulously restored and is now filled with the author’s possessions including his writing desk and books. It is now operated it as a museum. And since many of its furnishings remained in the family, a visit there is one of the most authentic experiences of mid-19th century life anywhere in the country.

Losing Matilda Hoffman had been a crushing blow to Washington Irving, from which he never recovered. Thirty years after her death, he still could not bear to hear her name spoken or any reference to her. While Irving was visiting at the home of Matilda’s father, Mr. Hoffman’s granddaughter offered to play a song for Irving.

As she was taking her music from the drawer, a faded piece of embroidery fell on the floor. “Washington,” said Mr. Hoffman, picking it up, “this is a piece of poor Matilda’s workmanship.” Irving, who had been talking happily before, suddenly fell silent, and in a few moments got up and left the house, and did not return.

From 1848 to 1859, Washington Irving served as President of Astor Library, which would eventually become the New York Public Library.

By the fall of 1859, his health was beginning to fail. On November 28, 1859, while preparing to retire, he commented, “Well, I must arrange my pillows for another weary night. If this could only end!” Washington Irving died that night.

After his death, Irving’s heirs opened a carefully guarded box to which he always kept the key. Inside it they found a miniature portrait, a lock of fair hair, and a scrap of paper in Irving’s handwriting which read simply: Matilda Hoffman. He had kept her Bible and Prayer Book; they were placed nightly under his pillow in the days immediately following her death and thereafter carried with him during his many journeys.

My Favorite Washington Irving Quote:

There is a sacredness in tears. They are not the mark of weakness, but of power. They speak more eloquently than ten thousand tongues. They are the messengers of overwhelming grief, of deep contrition, and of unspeakable love.

SOURCES

Rebecca Gratz and Matilda Hoffman

Eminent Women: Matilda Hoffman

Washington Irving, by Charles Dudley Warner (ebook)

What a lovely man, so very talented and versatile. What a shame, and how painful it must have been to have to live his whole life without the girl of his dreams; to find her only to be cheated by her illness and subsequent death; to have to continue without the joy of marrying her and living happily together. He was never the same, yet went on to achieve greatness through his ability to persevere in the face of this tragedy. A man to greatly admire and appreciate who dedicated himself to his work without the benefit of

his loving, ideal soul mate to comfort, cherish and inspire him.

The above comment refers to Washington Irving and his fiancee Matilda Hoffman.