19th Century Abolitionist and Feminist

Sarah Pugh (1800-1884) was a dedicated teacher who founded her own school and devoted her life to the abolition of slavery and advancing the rights of women. She was co-founder and leader of the influential Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, a women’s group open to all races.

Born in Virginia in 1800, Sarah Pugh moved to Philadelphia at the age of three when her father died, and spent her life in that city. She attended Westtown boarding school for two years, and in 1821 began teaching at the Friends School of the 12th Street Meeting. When the Quakers split the Hicksite and Orthodox factions, Sarah resigned and started her own school, which she ran for most of her life.

Career in the Abolitionist Movement

In the 1830s, the issue of slavery was increasing polarizing the nation. Living in a border state with many economic and social ties to the South, Pennsylvanians were deeply divided in their attitudes toward slavery and toward the women who were actively participating in the growing abolition movement.

The first abolitionist organization, the American Anti-Slavery Society, was established in Philadelphia in December 1833. Lucretia Mott and Lydia White, Esther Moore and Sidney Ann Lewis were present but were not allowed to be delegates; they were permitted to observe the proceedings from the gallery. To the surprise of many, Mott asked the chairman if she could speak, and then addressed the delegates on several points.

Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society

The members of the new American Anti-Slavery Society encouraged the four women in attendance to create of a female antislavery society. Three days later, on December 9, 1833, Mott, Sarah Pugh and twenty other women met in a Philadelphia schoolroom to found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS). On December 14, they finalized their Constitution and Pugh served as its presiding officer from 1833 until 1870.

Within a year the women of the PFASS had established a school for African Americans, were promoting the boycott of goods manufactured by slaves, and began lobbying for emancipation. When the English abolitionist George Thompson spoke in Philadelphia in 1835, Sarah was converted to the immediate abolition of slavery.

In 1836 the PFASS sent a petition to Pennsylvania Senator Samuel McKean to present to Congress. McKean responded: “I have received your petition bearing the signatures from 3,300 women of Philadelphia and I will present it. But you cannot be ignorant of the extreme sensibility of the subject.” In 1837 Lucretia Mott and Sarah Pugh joined the executive board of the newly formed Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.

From 1836 to 1854 the PFASS donated $13,845 – the rough equivalent of close to $400,000 today – to the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, supported the Underground Railroad through its contributions to the Philadelphia Vigilant Committee, and organized in 1837 to aid escaped slaves in southeastern Pennsylvania. The women of the PFASS continued their support even after doing so became illegal with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850.

Boycott of Slave Labor Goods

The practice of refusing to buy goods produced by slave labor originally began in the 1750s as part of the Quaker reformation. Quakers like John Woolman claimed slavery violated Christian principles of universal brotherhood. Woolman urged Quakers to reject items produced by slave labor goods as only the slaves’ masters profitted from their work. This boycott remained a predominantly Quaker movement until the 1780s.

After Parliament failed to pass a slave trade abolition bill in the spring of 1791, British abolitionists urged consumers to join a national boycott of slave-grown sugar. Baptist printer William Fox wrote An Address to the People of Great Britain on the Utility of Refraining from the Use of West India Sugar and Rum, which inspired British and American abolitionists to focus their energies on a boycott of West Indian produce.

Fox calculated that if just one family consuming five pounds of sugar per week abstained from sugar, that family could save the life of one slave. Ladies’ tea tables were targeted as these were among the most popular sites for consumption of slave-grown sugar. Women were now encouraged to reject sugar stained with “the blood of their fellow creatures.”

New York Quaker Elias Hicks wrote Observations on the Slavery of Africans and Their Descendants, and on the Use of the Produce of Their Labour in 1811. Still the boycott did not regain the momentum of the 1790s until 1824 when British Quaker abolitonist Elizabeth Heyrick suggested that the immediate, uncompensated abolition of slavery was the only solution to the problem.

In the United States men and women who had been influenced by Heyrick’s views organized free-produce societies. However, shop owners struggled to maintain a steady supply of slave-free goods for their customers. In an attempt to solve this problem, American abolitionists organized the Requited Labor Convention in 1838.

In October 1838 convention delegates established the American Free Produce Association (AFPA), the first national organization dedicated to the promotion of free-labor goods. Unfortunately, the AFPA failed to gain support. Still the boycott of these goods continued through the American Civil War, with support from Quakers, black abolitionists and the women of the PFASS, who emphasized the morality of free produce.

In the United States men and women who had been influenced by Heyrick’s views organized free-produce societies. However, shop owners struggled to maintain a steady supply of slave-free goods for their customers. In an attempt to solve this problem, American abolitionists organized the Requited Labor Convention in 1838.

In October 1838 convention delegates established the American Free Produce Association (AFPA), the first national organization dedicated to the promotion of free-labor goods. Unfortunately, the AFPA failed to gain support. Still the boycott of these goods continued through the American Civil War, with support from Quakers, black abolitionists and the women of the PFASS, who emphasized the morality of free produce.

In the United States men and women who had been influenced by Heyrick, including Quaker abolitionists James and Lucretia Mott, organized free-produce societies. In 1833 the American Anti-Slavery Society and the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS) included free-produce resolutions in their founding documents. However, shop owners struggled to maintain a steady supply of slave-free goods for their customers.

Quaker abolitionist Sarah Pugh stated in 1841: “The great mass of abolitionists need an abstinence baptism.” Speaking at the third annual meeting of the American Free Produce Association, Pugh claimed many abolitionists were stained by the “taint of slavery” through their continued consumption of goods produced by slave labor.

Abolitionists urged consumers to boycott products that were produced by slave labor such as sugar, indigo, rice and cotton. For Pugh and other like-minded abolitionists, part of being an abolitionist meant refusing to benefit from slave labor. Still other abolitionists focused on the enormous wealth vested in slaves, arguing that a boycott of these goods would strike at the economic root of African slavery.

In an attempt to increase the supply and quality of free-labor goods, George W. Taylor and other Quakers established the Free Produce Association of Friends of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1845. African American abolitionists focused on the economics of slave and free labor, like Henry Highland Garnet who toured Great Britain in 1850, promoting free produce.

Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women

The first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women was held on May 9, 1837. Approximately 200 women gathered in New York City to discuss their role in the American abolitonist movement.

Prominent women in attendance included Sarah Grimke and Lydia Maria Child. The convention was a monumental step, both for the women’s rights movement and the abolition movement, but it receives very little historical attention.

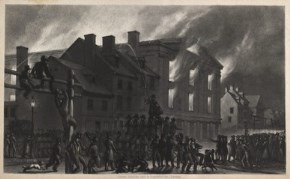

In 1838 funds were raised to build Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia to be the local abolitionist headquarters. When the second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women held its first meeting at the Hall in May 1838, growing tensions over race and gender exploded into violence. On May 17, a huge mob of pro-slavery protestors, enraged by the presence of white women publicly interacting with both men and African Americans, gathered outside the Hall.

Image: Pennsylvania Hall was burned to the ground by a pro-slavery mob only four days after it was built.

Sarah Pugh was one of the women who escaped the building in pairs – one black woman and one white woman arm in arm – which left would-be attackers bewildered long enough for all the women to escape. The mob returned the following day and burned the hall to the ground. The convention continued the next day at Sarah Pugh’s schoolroom, where they pledged to expand the relationship between blacks and whites.

The burning of Pennsylvania Hall did not deter the members of the PFASS; they focused more and more of their efforts on raising funds for the abolition movement and the emerging Underground Railroad through the staging of annual fairs. Following the lead of the Boston Female Anti-slavery Society, the PFASS held its first fair in 1836, selling baked goods, needlework, art pieces and pottery with anti-slavery designs. In the years that followed the fairs grew in size and scope.

World Anti-Slavery Convention

In June 1840, Sarah Pugh was chosen as a delegate to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, along with Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Female delegates had been officially denied registration, but Pugh had written to protest this and to advise the organizers that at least three women would be attending.

A vote was taken among the male delegates of the British Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, and the women were excluded as delegates to the Convention by an overwhelming majority. The women were fenced off behind a bar and curtain, similar to those used in churches to screen the choir when they are not singing. On behalf of the Pennsylvania delegation, Pugh stated:

My friend George Thompson, yonder, can testify to the faithful services rendered to this cause by those same women. He can tell you that when “gentlemen of property and standing”… undertook to drive him from Boston, putting his life in peril, it was our women who made their own persons a bulwark of protection around him.

And shall such women be refused seats here in a Convention seeking the emancipation of slaves throughout the world? What a misnomer to call this a World’s Convention of Abolitionists, when some of the oldest and most thorough-going Abolitionists in the world are denied the right to be represented in it by delegates of their own choice.

During the 1850s Sarah Pugh often traveled with her her close friend and noted reformer Lucretia Mott, attending women’s rights conventions. Her other friends included Susan B. Anthony and her niece, women’s and children’s rights activist Florence Kelley. Sarah never married.

Pugh returned to England in 1851 and spent seventeen months explaining the anti-slavery movement to British audiences.

During the Civil War, Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society members devoted their efforts to the support of the Union war effort, and after the end of slavery in 1865 to the campaign for the right of African Americans to vote. The Society organized its final fair, to support the movement for black suffrage, in 1869, then disbanded in 1870 after ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment.

After the Civil War Pugh established several schools for freed slaves and their children, and became a prominent suffragist, working for the Pennsylvania Woman’s Suffrage Association. She also became involved in the Moral Education Society, an organization that campaigned to prevent the licensing of prostitutes, believing that only their customers should be penalized.

In her mid-70s she signed the Declaration of Rights for Women in 1876, which was presented to the Centennial Exposition of 1876. The first world’s fair held in the United States, the Expo celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. This is an excerpt from that document:

It was the boast of the founders of the republic, that the rights for which they contended, were the rights of human nature. If these rights are ignored in the case of one half the people, the nation is surely preparing for its own downfall… The recognition of a governing and a governed class is incompatible with the first principles of freedom.

Woman has not been a heedless spectator of the events of this century, nor a dull listener to the grand arguments for the equal rights of humanity. From the earliest history of our country, woman has shown equal devotion with man to the cause of freedom, and has stood firmly by his side in its defense. Together, they have made this country what it is. Woman’s wealth, thought and labor have cemented the stones of every monument man has reared to liberty….

We ask of our rulers, at this hour, no special favors, no special privileges, no special legislation. We ask justice, we ask equality, we ask that all the civil and political rights that belong to citizens of the United States, be guaranteed to us and our daughters forever.

Sarah Pugh died in 1884 after a long and fruitful life and was buried at Fair Hill.

SOURCES

NNDB: Sarah Pugh

Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society

NWHM: Women In The Abolition Movement

Blood-Stained Goods: The Transatlantic Boycott of Slave Labor

A question, please: what is known about Sarah Pugh’s life before 1821, aside from the brief descriptions above about her father’s death and attendance at Westtown boarding school? What are the primary sources which provide such information? Lastly, was there an association or relationship between Sarah Pugh and the Lewis family (Evan Lewis, son of Evan Lewis and Jane Meredith, born in Radnor, Delaware County, PA 8/19/1782, died 3/23/1834) and Sidney Ann Gilpin, daughter of James Gilpin and Sarah Little, born in Wilmington, Delaware 2/28/1795, died 3/23/1882)? I am a descendant of the Lewis family through Enoch and Charlotte Lewis and their daughter May Thorn Lewis Gannett. Thank you.