American Women Newspaper Publishers

In the eighteenth century, women often worked alongside their husbands and brothers to publish a newspaper as a family business. In some cases, the wife became the publisher after her husband took ill or died, usually until a son could take over the paper. The influence of these women in publishing as active participants in the business is an enduring feature of newspaper history to the present day.

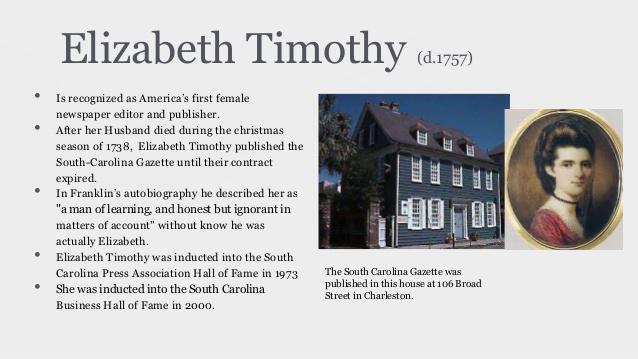

Image: Elizabeth Timothy, America’s first female newspaper publisher, 1738

The South Carolina Gazette, Charleston, South Carolina

18th Century Women Publishers

In the 1700s, women edited approximately 16 of the 78 small, family-owned weekly newspapers circulating throughout the American colonies. Even if they did not run the printing operations, wives, mothers and sisters probably contributed significantly to many of the other publications. Because of their overwhelming duties as wives and mothers, women typically assumed control of a publication only after the death of a male relative.

Women were restricted from becoming professional publishers through custom and law in America until the late 19th century, and only became involved in the production of newspapers if they or their family owned the title. As is the case with many small businesses, the various tasks of operating a newspaper often overlapped. Women worked as publishers, printers, typesetters, journalists, and carved wooden engravings for illustrations.

Elizabeth Timothy

In 1738, following the death of her husband Lewis Timothy, Elizabeth Timothy became the first woman publisher of a newspaper in America. She operated the South Carolina Gazette in Charleston for seven years in partnership with founding father Benjamin Franklin. She ran the periodical under the name of her 13-year-old son, Peter – as a woman, she could not publish the paper under her own name.

In her first issue of the Gazette, Timothy addressed her readership with a sentimental message on January 4, 1739, asking for their continued support:

Wherefore I flatter myself that all those persons, who by subscription or otherwise who assisted my late husband, on the prosecution of the said undertaking, will be kindly pleased to continue their favors and good offices to his poor afflicted widow and six small children and another hourly expected.

Benjamin Franklin, who had been friend and partner of Lewis Timothy, praised Elizabeth for her skills, noting that he preferred her business style to that of her husband. “Her accounts were clearer, she collected on more bills, and she cut off advertisements if payments were not current.” Franklin also commented in his autobiography that Elizabeth operated the Gazette:

[with] regularity and exactitude… and managed the business with such success that she not only brought up reputably a family of children, but at the expiration of her term was able to purchase of me the printing house and establish her son to it.

Anne Catherine Hoof Green

During her husband’s illness, Anne Catherine Green, mother of six, published the Maryland Gazette and continued after his death in 1767. However, her husband had left her deep in debt. Green moved her print shop supplies into the family home to help her manage her tasks as a single mother and business owner.

She took over the contract as printer for the Maryland legislature, and in that year, she also issued the volumes of Acts and Votes and Proceedings of the provincial assembly on schedule. Anne Green also asserted a forward-thinking feminist principle when she won the right to be paid the same amount her husband had received for the same work. And in three short years, she was able to buy the printing business and the house they had been renting.

Image: Anne Catherine Hoof Green

Publisher of The Maryland Gazette leading up to the Revolution, 1767

Her accomplishments as a printer, publisher, and a single mother encouraged the position and abilities of women in a time when they were expected to remain in a domestic role.

Under Anne Green’s skillful direction, the paper became a powerful force in the community. Green used her highly influential position to champion the Patriots’ cause. In the Maryland Gazette, she publicized the debates over the Stamp and Townshend Acts and published the anti-British Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1768) written by John Dickinson – all precursors of the American Revolution.

Clementina Bird Rind

Women publishers were among the first to record, comment on and publicize the events leading up to the Revolutionary War. After her husband died in 1773, Clementina Bird Rind took over publication of Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette for her dear infants: William, John, Charles, James and Maria. Rind was careful to preserve the integrity of the newspaper’s motto: Open to ALL PARTIES, but Influenced by NONE.

During her tenure as publisher, Rind’s periodical highlighted new scientific research, debates on education and philanthropic causes. She is also known for being the first to print Thomas Jefferson’s Ideas on American Freedom and for her staunch insistence that writers refrain from using pseudonyms or anonymity. She stated, “As I am in some measure, amenable to the public for what appears in my Gazette, I cannot think myself authorized to publish an anonymous piece.”

In May 1774, the House of Burgesses recognized her as Virginia’s official public printer. Rind became popular with her criticism toward England, denouncing its authority. In 1774 the Virginia Gazette published Thomas Jefferson’s pamphlet A Summary View of the Rights of British America, in which he laid out for delegates to the First Continental Congress a set of grievances against the King and Parliament’s response to the Boston Tea Party.

Anna Zenger

Peter Zenger was arrested for libel in 1734, when his newspaper, the New York Weekly Journal, published multiple articles criticizing the Royal Governor of New York. His wife Anna Zenger then assumed control of the publication, becoming one of the earliest women publishers. Zenger gave his wife printing instructions during their visits in his prison cell.

Zenger was brought to trial for criminal libel in April 1735. He was defended by Andrew Hamilton, uncle of Founding Father Alexander Hamilton. The judge was ready to direct the jurors to retire and return with a guilty verdict, but Hamilton argued that the articles Zenger published were not libelous because they were true. He appealed to the jury to stand up to arbitrary power that would prevent the colonists from speaking and writing the truth.

On August 5, 1735, twelve New York jurors ignored the instructions of the Governor’s hand-picked judge and returned a verdict of not guilty, concluding that Zenger’s articles were based on fact, and therefore not libelous. This case and others like it prompted the Founding Fathers to emphasize the right to freedom of the press in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

After his release from prison, Zenger resumed his position as publisher of the New York Weekly Journal. In 1736 he wrote an account of his trial, A Brief Narrative of the Case and Tryal of John Peter Zenger. Anna again became the publisher of the Journal when Peter died in 1746, and she continued to criticize the Governor and English rule over the colonies.

Mary Katherine Goddard

In 1762, wealthy widow Sarah Updike Goddard financed Rhode Island’s Providence Gazette. Although her son William Goddard was the editor, Sarah and her daughter Mary Katherine Goddard were the paper’s primary operators and publishers of the Gazette and the annual West’s Almanack.

The Goddards sold the Gazette in 1768 and moved to Philadelphia, where they published the Pennsylvania Chronicle. Sarah died in 1770, but having been trained by her mother in writing and editing, Mary Katherine was well prepared to continue her career. She and her brother subsequently moved to Baltimore and began to publish the Maryland Journal. In 1775 she was also appointed the first postmistress in Baltimore and in colonial America.

Although Mary Katherine Goddard is most often regarded as the first woman publisher in America in lists of Famous Firsts for Women, there are clearly other women in publishing long before Goddard, the most obvious of whom are Anna Zenger and Elizabeth Timothy. Goddard may have been the first woman to proclaim herself as publisher, putting “Published by M.K. Goddard” on the masthead on May 10, 1775.

Image: Mary Katherine Goddard, publisher of the Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, 1774

The only newspaper published in Baltimore during the Revolution

In January 1777, Goddard became the most famous woman publisher of the American Revolution when she was the first to reveal to the public who had signed the Declaration of Independence. Well aware that they were committing treason against the mother country, the signers had omitted their names from the original publication of this historic document in July 1776. Six months later, the Continental Congress authorized Goddard’s Maryland Journal to publish the Declaration along with the names of the signers.

Unfortunately, Goddard’s career quickly declined once American independence was won. Her experience exemplifies the gradual decline of the status of American women after the American Revolution. Her brother William returned to Baltimore and won control of the Maryland Journal in 1784. When the new federal government established a National Post Office in 1789, the Postmaster General removed Goddard from her postal position, despite her appeal to George Washington and petitions from over two hundred prominent Baltimore men.

Changes in Publishing

Our nation began to industrialize in the early nineteenth century, and small, family run printers and publishers gave way to larger corporate publishers. The growth of the school system and more educational opportunities for women meant that literacy rates also rose, and periodicals flourished. By the 1850s, four-page weeklies and monthly magazines were in full circulation throughout the country.

Publishers appealed to this new readership by deepening their pool of skilled writers in women’s magazines and by adding ‘society pages’ in newspapers and ‘women’s sections’ in magazines. Furthermore, new opportunities in reporting were sought out by pioneering, bold women, while causes such as abolitionism and women’s rights opened new doors for women publishers.

The new nation’s first unisex periodical, Gentlemen and Ladies’ Country Magazine, began in 1784, the year after the American Revolution ended. It included articles specifically for women and requested submissions from women writers. From then until the Civil War, 25 women’s magazines were in circulation. However, they were bound by the social restrictions of the time, publishing articles fit for a female audience: fashion, recipes, poetry, and marriage and childrearing advice.

19th Century Women Publishers

Women who were able to become publishers during the 19th century often faced discrimination, not least in terms of salary, where they were paid just one-third of what men earned. This was one of the reasons why women in the printing business organized their own trade union in 1870. Some African American women also took charge of periodicals.

Sarah Josepha Hale

Widowed in 1822 with five children to support, Sarah Josepha Hale began a career as a professional writer. In 1828, she moved to Boston and assumed the editorship of America’s first magazine tailored exclusively for women, Boston Lady’s Magazine. The magazine was billed at the time as “the first magazine edited by a woman for women… either in the Old World or the New.”

Hale conceived of the magazine as promoting ‘female improvement’ and used her column The Lady’s Mentor to push that cause. She used the publication to broadcast her support for women’s education and their and involvement in professions such as academia, medicine and writing. However, she supported the existing social standards and the ideology of separate male and female spheres. Therefore, she refrained from participating in the emerging women’s rights movement, insisting that women should not enter the masculine fields of business, politics and government.

By 1836, outstanding unpaid subscriptions for Boston Lady’s forced Hale to move to Philadelphia and merge her magazine with that of Louis Godey. The partners established Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1837. Although it was expensive, Godey’s soon became the most widely read periodical in the nation. Hale continued to write on topics such as women’s education and later reevaluated her perspective on separate male and female social spheres, but never formally joined the suffrage movement.

Sarah Josepha Hale also wanted to promote a new American literature, so rather than publishing primarily reprints of British authors, as many other periodicals did, she solicited work from American writers. She wrote a considerable portion of each issue herself. Other contributors included Lydia Sigourney and Sarah Helen Whitman.

Cornelia Walter

Talented American women found opportunities in the newspaper business as publishers and as editors. In 1842 after the death of Lynde Walter, editor of the Boston Transcript, his sister Cornelia Walter took over, becoming the first woman editor of a major daily newspaper in the United States. One of the highlights of her career came on August 3, 1842, when she reported the plight of black citizens who had been victimized and left homeless during a race riot in Philadelphia.

When Cornelia Walter retired from the newspaper business to get married in 1847, her departure was noted by newspapers around the country, and the Transcript’s owners commended her work:

The experiment of placing a lady as the responsible editor of a Paper was a new and doubtful one. It was a bold step on her part to undertake so much labor and responsibility. She made the trial with fear and trembling, and her success has been triumphant. The task had never been undertaken in this or any other country, to the knowledge of the publishers, by one of her sex; it was consequently the more trying, and her victory the more brilliant.

Ann Stephens

Inspired by the success of Godey’s, publisher Charles Peterson and writer Ann Stephens launched Peterson’s Magazine in 1842. Stephens served as editor from 1842-1853. Unlike others who entered the field only after the death of a husband, Stephens established herself as the primary financial provider for her family. While she worked and traveled for business, her husband tended to the children at home.

Although Peterson’s was similar to Godey’s both aesthetically and topically, Peterson’s made a greater commitment to publishing works by women writers. Both magazines were published from Philadelphia, and by the 1860s, each magazine could claim more than 150,000 subscribers. Amazingly enough, Stephens also found time to write two-dozen novels, some of which won high literary praise.

Godey’s and Peterson’s dominated the women’s magazine market in the first half of the 19th century, but the Civil War marked a turning point in this, as in so many things. Improvements in distribution techniques, the mechanics of printing, and a growing and diversified national readership prompted the birth and growth of new, innovative periodicals geared toward a broader female readership.

Today, Exceptional Women in Publishing (EWIP), a non-profit organization, offers programs that are meant to foster growth for smaller, independent publications by and for women and to offer a range of community building and professional development programs through its gatherings. EWIP’s mission is twofold: to educate, empower and support women in publishing and to educate, empower and support women through the power of publishing.

SOURCES

Women Journalists

Women and the News Business

18th Century American Women: Clementina Rind

Women with a Deadline: Female Printers, Publishers, and Journalists

Enjoyed this article.

Did you consider listing Anne Newport Royall?