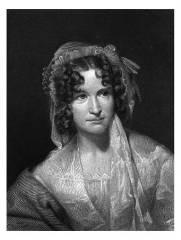

Sarah Helen Whitman was a poet, essayist and fiancee of author Edgar Allan Poe. Whitman and Poe were engaged, and had her family not interfered in the relationship, they might have married. She was also active in the women’s suffrage movement in Rhode Island as well as in other efforts at social reform.

Sarah Helen Power was born in Providence, Rhode Island on January 19, 1803, six years to the day before Edgar Allan Poe. Reading from an early age, Sarah was given a good education. She began writing poetry while at school, and beginning in the 1820s, her poetry appeared in newspapers, magazines, annuals and gift books.

On July 10, 1828, Sarah Power married John Winslow Whitman, a young lawyer from Massachusetts whom she met while he was a student at Brown University. The couple settled in Boston where he practiced law and served as the editor of several short-lived literary magazines. Whitman died in 1833. They had no children.

Transcendentalism

Sarah Whitman’s husband had introduced her to the Boston circle of writers and critics, and she became acquainted with a group called the Transcendentalists. Transcendentalism probably did not alter Whitman’s outlook so much as it defined convictions she had held all along – liberal convictions such as self-reliance, nonconformity, independence, intuition and the dominance of spirit.

Transcendentalism as spelled out by Ralph Waldo Emerson was the dominant philosophy in Providence, and Emerson himself visited the city often and delivered lectures there. Whitman became personally acquainted with him early in the 1830s. Another prominent Transcendentalist with whom Whitman was acquainted was Margaret Fuller, who resided in Providence while teaching in the Greene Street School founded upon the educational theories of Bronson Alcott.

Whitman was widely read: in one of her essays alone she cites thirty-three authors and three current periodicals. She was acquainted with many prominent contemporaries – among them Thomas Bailey Aldrich, Henry Ward Beecher, Park Benjamin, Orestes Brownson, General Benjamin Butler, Frances Sargent Osgood, Richard Henry Stoddard, Fanny Kemble and Nathaniel Parker Willis.

Literary Career

During the fifteen years following the death of her husband, Sarah Whitman began to establish a reputation as a poet and essayist. She continued publishing poetry, often in ladies’ magazines of the day. She was a talented poet and an insightful critic of literature and art, as well as a commentator upon the contemporary scene, including politics; architecture; manners; fashions in ideas, clothing and religion; and issues pertaining to her beloved city of Providence.

Sarah Josepha Hale in her Ladies’ Wreath in 1837 republished four of Whitman’s poems. Anne C. Lynch published six in her The Rhode-Island Book in 1841. And in 1849 the anthologist Rufus Griswold awarded Whitman’s poems a prominent place in his The Female Poets of America. In 1853 George H. Whitney of Providence published a collection of her poems titled Hours of Life, and Other Poems.

Sarah Whitman’s contemporaries considered her an accomplished poet and singled out especially her “keen observation and delicate description of nature.” She was also a prolific essayist. Her early essays, written during the 1830s and 1840s, cover a wide range of topics, from the “Nature and Attributes of Genius” to “The Scenery of Autumn.”

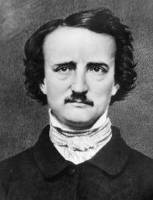

Image: Edgar Allan Poe

Relationship with Edgar Allan Poe

Sarah Whitman and Poe first crossed paths in Providence in July 1845. Poe was attending a lecture by friend and poet Frances Sargent Osgood. As Poe and Osgood walked, they passed Sarah Whitman’s home while she was standing in the rose garden behind her house. Poe declined to be introduced to her. By this time, Whitman was already an admirer of Poe’s stories.

Her friend Annie Lynch asked Whitman to write a poem for a Valentine’s Day party in 1848. She agreed, and wrote one for Poe, though he was not in attendance. Poe heard about the tribute and returned the favor by anonymously sending his previously-printed poem “To Helen.” Whitman may not have known it was from Poe himself and she did not respond. Three months later, Poe wrote her an entirely new poem, “To Helen,” referencing the moment he first saw her in the rose garden behind her house.

Sarah Helen Whitman met Edgar Allan Poe for the first time at her home in Providence, Rhode Island on September 21, 1848. Both were widowed; he was in his thirty-ninth year, and she in her forty-fifth. Poe spent four days in Providence with her, then launched an intense and stormy courtship, and the two exchanged letters and poetry.

Sarah Whitman letter to Edgar Allan Poe, September 27, 1848:

You will, perhaps, attempt to convince me that my person is agreeable to you – that my countenance interests you: – but in this respect I am so variable that I should inevitably disappoint you if you hoped to find in me to-morrow the same aspect which won you to-day. And, again, although my reverence for your intellect and my admiration of your genius make me feel like a child in your presence, you are not, perhaps, aware that I am many years older than yourself.

I fear you do not know it, and that if you had known it you would not have felt for me as you do… I find that I cannot now tell you all that I promised. I can only say to you that had I youth and health and beauty, I would live for you and die with you. Now, were I to allow myself to love you, I could only enjoy a bright, brief hour of rapture and die – perhaps [illegible].

In Poe’s twelve-page reply, he references the above passage in her letter:

Ah, beloved, beloved Helen the darling of my heart – my first and my real love! – may God forever shield you from the agony which these your words occasion me!… You will never, never know… the hopeless, rayless despair with which I now trace these words… But ah, darling! if I seem selfish, yet believe that I truly, truly love you, and that it is the most spiritual of love that I speak, even if I speak it from the depths of the most passionate of hearts.

Think – oh, think for me, Helen, and for yourself! Is there no hope?… May not this terrible [disease?] be conquered? Frequently it has been overcome. And more frequently are we deceived in respect to its actual existence. Long-continued nervous disorder – especially when exasperated by ether… will give rise to all the symptoms of heart-dis[ease an]d so deceive the most skillful physicians… But admit that this fearful evil has indeed assailed you.

Do you not all the more really need the devotionate care which only one who loves you as I do, could or would bestow? On my bosom could I not still the throbbings of your own? Do not mistake me, Helen! Look, with your searching – your seraphic eyes, into the soul of my soul, and see if you can discover there one taint of an ignoble nature! At your feet – if you so willed it – I would cast from me, forever, all merely human desire, and clothe myself in the glory of a pure, calm, and unexacting affection.

I would comfort you – soothe you – tranquillize you. My love – my faith – should instil into your bosom a praeternatural calm. You would rest from care – from all worldly agitation. You would get better, and finally well. And if not, Helen, – if not – if you died – then at least would I clasp your dear hand in death, and willingly… go down with you into the night of the Grave.

Write soon… but not much. Do not weary or agitate yourself for my sake… And now, in closing this long, long letter, let me speak last of that which lies nearest my heart – of that precious gift which I would not exchange for the surest hope of Paradise. It seems to me too sacred that I should even whisper to you, the dear giver, what it is. My soul, this night, shall come to you in dreams and speak to you those fervid thanks which my pen is all powerless to utter.

Edgar

In my research I found a statement that Sarah Helen Whitman had a heart condition that she treated with ether which she breathed in through her handkerchief. This puzzled me. I could find no information as to why ether would be used to treat a heart condition (to dull the pain?), but I found a substantial amount of information about ether addiction, which can be serious.

I also found this excerpt about Whitman in Hervey Allen’s 1934 book, Israfel; The Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe:

She was delicately beautiful, veiled, mysterious, and elusive. She dressed in light silken draperies, and, as she passed, shielding her eyes from the too garish light of day by a fan, one glimpsed a spiritual dream of womanhood gliding by upon dainty slippers, following by undulating scarfs – and a faint, deathly-sweet odor of a handkerchief soaked in ether.

Sarah saw Poe again when he lectured in Providence sometime around December 21, 1848, during which he recited a poem directly to her. She agreed to an “immediate marriage,” and they chose the wedding date of December 25, 1848, despite criticism of the relationship from friends and enemies alike. Sarah insisted on one condition: that he stop drinking.

Sarah called off the wedding two days later, after supposedly receiving an anonymous letter suggesting that Poe had broken his vow to her to stay sober. Poe returned from Providence to New York, never to see her again. Poe sent a letter to Whitman dated January 25, 1849, addressed Dear Madam:

In commencing this letter, need I say to you, after what has passed between us, that no amount of provocation on your part, or on the part of your friends, shall induce me to speak ill of you even in my own defence?… Heaven knows that I would shrink from wounding or grieving you! I blame no one but your Mother – Mr Pabodie will tell you the words which passed between us, while from the effects of those terrible stimulants you lay prostrate without even the power to bid me farewell. Alas! I bitterly lament my own weaknesses, & nothing is farther from my heart than to blame you for yours…

So far I have assigned no reason for my declining to fulfil our engagement. I had none but the suspicious & grossly insulting parsimony of the arrangements into which you suffered yourself to be forced by your Mother… It has been my intention to say simply, that our marriage was postponed on account of your ill health. Have you really said or done anything which can preclude our placing the rupture on such footing? If not, I shall persist in the statement & thus this unhappy matter will die quietly away –

E. A. Poe

Apparently Sarah’s mother had helped persuade her to insist on an agreement with Poe to turn over her (Sarah’s) property to her mother, presumably to protect it from him. Thus the reference to Sarah’s mother and the words which passed between us, while from the effects of those terrible stimulants you lay prostrate without even the power to bid me farewell. I assume this again refers to the ether.

Though Poe seems to have felt relief at breaking off with her, Whitman was regretful and recorded her regret in poems she addressed to him, a half dozen written before Poe’s death and at least a dozen more over the four years immediately thereafter.

On October 3, 1849, Edgar Allan Poe was found on the streets of Baltimore delirious, “in great distress, and… in need of immediate assistance”, according to the man who found him. Oddly, was wearing clothes that were not his own, but he was never coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in this dire condition. He died on Sunday, October 7, 1849. All medical records, including his death certificate, have been lost.

Much controversy swirled about Poe during the first decade following his death, and Sarah Whitman always rose to his defense, a defense culminating in the publication in 1860 of Edgar Poe and His Critics, eleven years after Poe’s death. In this book she argues that Poe should not be condemned but appreciated, because he stood at the forefront of an illustrious company of contemporaries.

In the 1870s, a new generation of biographers, bent upon rescuing his reputation from the defamation it had suffered immediately upon his death, led a revival of interest in Poe. Almost until her own death, Whitman served these competing biographers, both as a living resource and as a kind of research assistant.

To her three month relationship with Poe, Sarah Whitman owes much of the recognition she enjoys today, principally among Poe’s biographers. They identify her as Poe’s Helen, as that eccentric Providence widow who came within a hairbreadth of marrying him.

Feminism

Sarah Whitman’s liberalism led her to espouse both feminism and Spiritualism, two major movements that became popular in the area during the late 1840s. And she became involved in many of the causes of the New England activists: progressive education, women’s rights and universal suffrage.

Sarah Whitman was neither as strident a feminist as Margaret Fuller nor as militant as Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott and Paulina Wright Davis. She was, nonetheless, an active and prominent member of the movement. Whitman composed an old-fashioned verse satire for recitation at a suffragist banquet in 1871 titled “Woman’s Sphere,” which closes with this view of man/woman relationships:

Too long benighted man has had his way;

Indignant woman turns and stands at bay.

Old proverbs tell us when the world was new,

And men and women had not much to do,

Adam was wont to delve and Eve to spin;

His work was out of doors and hers within.

But Adam seized the distaff and the spindle,

And Eve beheld her occupation dwindle.Must she then sit with folded hands and tarry,

Till some fair sybil tell her “whom to marry?”

Better devote her time to ward committees,

To stumping States and canvassing the cities;

Better no more on flimsy fineries dote,

But take the field and claim the right to vote.

Whitman continued to write and publish poetry and essays until the end of her life, often assuming a mentor’s role with younger and newer writers. She was active in the women’s suffrage movement in Rhode Island as well as in other efforts at social reform. She also continued her involvement with Spiritualism, holding seances and writing about the subject, though she gradually moved from acceptance of Spiritualism to supporting investigations into its claims.

Sarah Helen Whitman died on June 27, 1878 at age 75 and is buried in the North Burial Ground in Providence. In her will, she left funds for the publication of a posthumous collection that was issued by Houghton, Osgood and Company of Boston in 1879 under the title Poems by Sarah Helen Whitman.

SOURCES

The Edgar Allan Poe Society

Wikipedia: Sarah Helen Whitman

About.com: Sarah Helen Power Whitman

Poetry Foundation: Sarah Helen Whitman