Sarah Grimke helped pioneer the antislavery and women’s rights movements in the United States. The daughter of a South Carolina slave-holder, she began as an advocate for the abolition of slavery, but was severely criticized for the public role she assumed in support of the abolitionist movement. In Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, and the Condition of Woman (1838), Grimke defended the right of women to speak in public in defense of a moral cause.

Childhood and Early Years

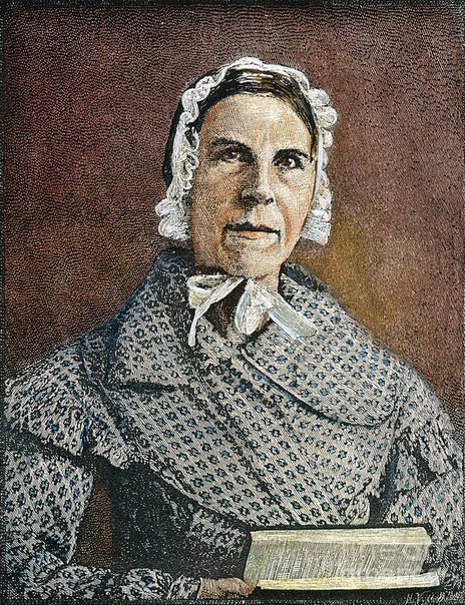

Sarah Moore Grimke was born on November 26, 1792, in Charleston, South Carolina. She was the eighth of fourteen children and the second daughter of Mary and John Faucheraud Grimke, a wealthy plantation owner who was also an attorney and a judge. The Grimkes lived alternately between a fashionable townhouse in Charleston and the sprawling Beaufort plantation in the country.

Like other large plantation owners, they kept scores of slaves, who did all the labor at Beaufort, from cotton picking to cooking to caring for the children. Slaves worked as nursemaids to the Grimkes’ fourteen children and each child was also assigned a constant companion, a slave of about the same age. Sarah later said that at age five she saw a slave being whipped, and tried to board a steamer to a place where there was no slavery.

A Young Girl’s Dream

Sarah’s early experiences with education shaped her future as an abolitionist and feminist. Throughout her childhood, she was keenly aware of the inferiority of her own education when compared to that of her brothers. Although everyone recognized her remarkable intelligence, Sarah could not pursue her dream of becoming a lawyer and following in her father’s footsteps.

Sarah studied constantly until her parents learned that she was planning on going to college with her brother Thomas, which was, of course, impossible in the first decade of the 1800s. (The first American women to earn Bachelor’s Degrees graduated from Oberlin College in 1841. The first woman permitted to practice law in America was Arabella Mansfield in 1869).

Thereafter, Sarah’s parents forbade her to study her brother’s books. Instead she received an education from private tutors on subjects like reading, writing, simple math and social etiquette. Young women might also be taught music, needlework, cooking and nursing, to be used in their daily lives as wives and mothers. Her father supposedly remarked that if Sarah “had not been a woman, she would have made the greatest jurist in the land.”

The Grimke family attended the Episcopal Church, where Sarah read Bible stories to slave children. From the time she was twelve years old, she also spent her Sunday afternoons teaching Bible classes to the young slaves on the family plantation. While she wanted desperately to teach them to read the scripture for themselves, her parents admonished her that teaching slaves to read had been against the law in South Carolina since 1740.

Still, Sarah secretly taught her personal slave to read and write, but when her parents discovered the young tutor at work, the vehemence of her father’s response was alarming. He was furious and nearly had the young slave girl whipped. Fear of causing such trouble for the slaves prevented Sarah from teaching any others.

When her brother Thomas went off to law school at Yale, Sarah remained at home, feeling that she was alone in her questioning the treatment of women, particularly in respect to education, and the institution of slavery. “Slavery was a millstone about my neck, and marred my comfort from the time I can remember myself.”

Unable to continue her education, thirteen-year-old Sarah was delighted when her sister Angelina was born on February 20, 1805. Mary Grimke was worn out from the demands of her huge household and from bearing fourteen children. Therefore, Sarah acted as a substitute mother to Angelina and became her main caretaker from infancy.

Each sister possessed a strong mind and kind soul and, in spite of growing up in a male-dominated, slave-holding southern family, the two shared the belief that all people are created equal. More than best friends, the Grimke sisters lived together most of their lives and later collaborated in their efforts to bring about social change in the 1830s.

Philadelphia and the Quakers

In 1818, as Sarah turned twenty-six and Angelina entered her teens, their father was deathly ill. Sarah was sent alone to accompany her father to Philadelphia in search of a cure, but his condition grew worse. During the months that Judge Grimke hovered between life and death, he leaned on Sarah heavily. The two grew so close that they “became fast friends” and Sarah regarded this “as the greatest blessing… that I have ever received from God.” As a result, Sarah became more self-assured, independent and morally responsible.

She was also on her own for the first time in the big city of Philadelphia, and the trip was a major turning point in Sarah’s life. It opened her eyes to life in the North, outside of slavery. In June 1819, Sarah and her father decided to take a short trip to the Atlantic coast, hoping that the sea air would do him some good. But it was too late – Judge Grimke died in Bordentown, New Jersey, with Sarah by his side.

Sarah remained in Philadelphia for a few months after her father’s death and, while waiting for a ship back to Charleston, she was introduced to the Society of Friends, or Quakers, whose views on slavery and gender equality matched her own. From her youth, Sarah believed that religion should take a more proactive role in improving the lives of those who suffered most; this was one of the key reasons she joined the Quaker community.

The Friends introduced Sarah to the works of Quaker leader John Woolman, and she was immediately inspired by his message. Woolman strongly condemned slavery as evil and was among the first to link the discrimination blacks faced in the North to the slavery of the South. Quakers also allowed women to become preachers and leaders within the church, and Sarah thought that could be her calling.

Sarah did not convert immediately, however, but returned to South Carolina in 1820 to weigh her decision. Upon her return, Sarah found the South unbearable. Having spent nearly a year in the North, she realized she could no longer live in the presence of slavery, even if it meant leaving her family. Within a month of her return and against her mother’s wishes, Sarah moved permanently to Philadelphia and joined the Quaker Society of Friends.

When Sarah returned to South Carolina for a visit in the spring of 1827, Angelina was impressed by the simplicity of her sister’s Quaker dress and lifestyle. When Sarah returned to Philadelphia, Angelina went with her and stayed from July to November of that year, returning home committed to the Quaker faith.

Angelina remained in Charleston, attempting to convert friends and family members, but the time finally came when she could no longer tolerate living with slavery. In November 1829, she joined Sarah in Philadelphia, and they became active members in the Society of Friends.

Sarah then began working towards becoming a member of the Quaker clergy, but she was continually discouraged by male members of the Philadelphia Society of Friends. Other women became Quaker ministers, like Lucretia Mott, but for whatever reason, Sarah was discouraged from doing so. She finally gave up when one church elder rudely interrupted one of her prayer meetings.

By 1832, both sisters had become very discouraged by their limited roles within the Philadelphia branch of the Quaker church. They longed to be more involved in the slavery issue. Meanwhile, in the country at large, explosive events were taking place. Antislavery speakers were flooding the East Coast with their messages, which included emancipation, abolition and recolonization, sending the nation’s black population back to Africa.

Anti-Slavery Writings

Reading in William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator, of the formation of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) in 1833, Angelina rushed to support his efforts. The AASS was the first interracial society that supported immediate emancipation of slaves, boldly declaring that “the Negro, free or slave, was a human being and a citizen and was to be considered as such.” Angelina attended AASS meetings in Philadelphia and became a member of the society’s committee for the improvement of people of color.

As race riots erupted in East Coast cities, Angelina felt compelled to become more involved in Garrison’s movement. On August 30, 1835, she wrote a letter that would change the sisters’ lives forever. Though she had never met Garrison, Angelina wrote, “I can hardly express to thee the deep and solemn interest with which I have viewed the violent proceedings of the last few weeks.” She told Garrison to keep up the fight and volunteered to join him, saying, “This is a cause worth dying for.”

Without Angelina’s permission, Garrison reprinted her moving letter in The Liberator, saying that he “could not, dared not suppress it.” The response to her letter was overwhelming, and Angelina and Sarah were thrust into the front lines of the fight against slavery. The Philadelphia Quakers were outraged by Angelina’s act (Quakers were supposed to receive permission from the church before doing anything on their own), but the antislavery community embraced the sisters.

As a result of their new-found friends and activities, the sisters moved to Providence, Rhode Island, to be with a more liberal group of Quakers. In early 1836 they began to write a series of antislavery pamphlets and books. Sarah wrote An Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States, followed by An Address to Free Colored Americans.

Anti-Slavery Speeches

Following publication of their writings, the Grimke sisters were invited to speak throughout the Northeast in 1836. They addressed Anti-Slavery Society conventions in New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Massachusetts and met all the famous abolitionists of the day, including Theodore Weld, who helped polish the sisters’ public speaking skills.

In the summer of 1837 Sarah and Angelina began a twenty-three week lecture tour in support of the abolitionist movement, unheard of for women of the time. Financing the trip themselves, the sisters visited sixty-seven cities, breaking new ground for women as public speakers. Sarah felt that she had finally found the place where she truly belonged, where her thoughts and ideas were encouraged.

However, she and Angelina soon faced severe criticism for their public speaking and involvement in the political sphere. Up to this time, it was virtually unheard of for women to speak out so boldly about the most controversial issues of the day. Their lectures were seen as unwomanly because they addressed mixed audiences of women and men – called promiscuous audiences at that time.

The sisters’ drew condemnation from religious leaders and traditionalists who believed that it was not a woman’s place to speak in public. Congregational ministers blasted the Grimkes in a public letter, saying that a woman becomes “unnatural” when she “assumes the place and tone of a man.” Catherine Beecher, who herself ran a groundbreaking women’s school, publicly criticized the sisters for not keeping to their proper place.

First Public Argument for Women’s Equality

As her lectures continued to elicit violent criticism, Sarah Grimke became acutely aware of her own oppression as a woman and the overwhelming parallels between the roles of women and slaves in American society. Both groups were denied the right to vote and the right to a secondary education, and both were treated as second-class citizens.

Thus, in 1837 Sarah was prompted to write Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women, the first document to link slavery to the unequal treatment of women. This was a series of letters addressed to Mary Parker, president of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, to defend the right of women to speak in public in defense of a moral cause.

Sarah in no way intended to suggest “that the condition of free women can be compared to that of slaves in suffering or degradation,” but women faced the same limitations as slaves in education and work opportunity. Letters was published serially in Massachusetts newspaper The Spectator and in book form in 1838.

Excerpts from Letters on the Equality of the Sexes:

Letter II, Woman Subject Only to God:

Woman has been placed by John Quincy Adams, side by side with the slave… I thank him for ranking us with the oppressed; for I shall not find it difficult to show, that in all ages and countries, not even excepting enlightened republican America, woman has more or less been made a means to promote the welfare of man, without due regard to her own happiness, and the glory of God as the end of her creation…

Lett VIII, On the Condition of Women in the United States:

Many women are now supported, in idleness and extravagance, by the industry of their husbands, fathers or brothers, who are compelled to toil out their existence, at the counting house or in the printing office or some other laborious occupation, while the wife and daughters and sisters take no part in the support of the family, and appear to think that their sole business is to spend the hard bought earnings of their male friends.

I deeply regret such a state of things, because I believe that if women felt their responsibility for the support of themselves or their families, it would add strength and dignity to their characters, and teach them more true sympathy for their husbands, than is now generally manifested…

Letter XII, Legal Disabilities of Women:

There are few things which present greater obstacles to the improvement and elevation of woman to her appropriate sphere of usefulness and duty, than the laws which have been enacted to destroy her independence, and crush her individuality; laws which, although they are framed for her government, she has had no voice in establishing, and which rob her of some of her essential rights. Woman has no political existence. With the single exception of presenting a petition to the legislative body, she is a cipher in the nation…

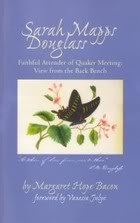

In 1838, Angelina married abolitionist Theodore Weld. Both black and white Americans attended the ceremony, including William Lloyd Garrison and black teacher and abolitionist Sarah Mapps Douglass. The Philadelphia Society of Friends officially expelled both sisters – Angelina for marrying a non-Quaker and Sarah for attending the wedding. The newlyweds and Sarah moved to a farm in Belleville, New Jersey.

Theodore Weld had been a severe critic of Sarah’s inclusion of women’s rights into the abolitionist movement. Apparently Weld sent Sarah a letter after a recent lecture she had given, detailing her inadequacies as a speaker. He tried hard to explain that he wrote this out of love for her, but he made it clear that she was damaging the cause, not helping it, like her sister.

After her marriage, Angelina retired to the background of the movement. After Weld’s letter, Sarah ceased lecturing altogether. The woman who had blazed trails for women in public speaking was now silent. However, as Sarah received many requests to speak over the following years, it is questionable whether her inadequacies which Weld described were really so bad.

Although the sisters no longer spoke publicly, they remained privately active as both abolitionists and feminists. In 1839, they published American Slavery As It Is: Testimony From a Thousand Witnesses, a collection of newspaper stories from southern papers written by southern newspaper editors. This book was later used as a source by Harriet Beecher Stowe for her 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Angelina’s first child was born in 1839; two more followed. The sisters focused their lives around raising the three Weld children and on demonstrating that they could manage a household without slaves. They took in boarders and opened a boarding school. They also kept up their correspondence with other anti-slavery and pro-women’s rights activists. One of their letters was read to the 1852 Women’s Rights Convention in Syracuse, New York.

Until 1854, Theodore Weld was often away from home, either on the lecture circuit or in Washington, DC. After that, financial pressures forced him to take up a more lucrative profession. That year Angelina, Theodore, Sarah and the children moved to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, where they operated a school until 1862. Emerson and Thoreau were among the visiting lecturers.

Later Years

During the Civil War, the sisters wrote articles supporting the Union and Abraham Lincoln. In March 1863, they penned “An Appeal to the Women of the Republic,” which urged women to rally to the cause of the Union and hold a convention to support the war effort. Angelina, now much stronger physically, addressed the convention, which was presided over by Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

Following the Civil War, the family moved to Hyde Park in Boston, Massachusetts, where they joined and served as officers of the Massachusetts Women’s Suffrage Association. In 1868 Sarah discovered three illegitimate nephews that her older brother had fathered with his personal slave. Welcoming them into the family, she worked to provide funds to educate them.

On March 7, 1870, when Sarah was seventy-nine and Angelina sixty-six, the sisters boldly declared a woman’s right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment by depositing ballots in a local election. They marched to the polling place in a driving snowstorm and were jeered by onlookers but because of their age, were not arrested. The gesture did not change the law against women voting, but it did receive a lot of publicity and was for the sisters a final “act of faith.”

Sarah Grimke died on December 23, 1873. Angelina suffered several strokes immediately following Sarah’s death, which left her paralyzed for the last six years of her life. She died on October 26, 1879.

The Grimke sisters had spent their lives promoting equality and free speech. They did not seek special treatment for women or African Americans, but simply the equal opportunity to succeed. In the immortal words of Sarah Grimke:

All I ask of our brethren is that they will take their feet from off our necks and permit us to stand upright on the ground which God intended us to occupy.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Sarah Grimke

God in America: Angelina and Sarah Grimke

Gale Encyclopedia of Biography: Sarah Grimke

Harvard.edu: Sarah Grimke and Angelina Grimke Weld

I first heard of the Grimke sisters in the 1960s or 70s on the NYC public radio station WNYC. The program, about special women, told that Sara Grimke was given a slave girl her own age as a birthday gift when she was ten. She secretly taught her slave to read (against rules) and treated her as a friend.

That was the part that stayed in my mind and puzzled me forever, to this day. Why was Sarah able to feel compassion, not such an unusual trait, that other girls in her similar situation did not? What made Sarah, who came from a traditional rich slave owning plantation family as did her peers, so different?

She was only TEN, not an age of unexpected independence. What was it in HER??