Educator of African American Girls

Myrtilla Miner (1815–1864) established the first school in Washington, DC to provide education beyond the primary level to African American girls in 1851 – at a time when slavery was still legal in the District of Columbia. Although the school also offered other courses, its emphasis from the outset was on training teachers. Miner’s progressive methods in education, her struggles against considerable opposition, and her dogged determination have earned her a place in American history.

Childhood and Early Years

Myrtilla Miner was born on March 4, 1815, near Brookfield, New York of humble parentage. Though always frail in health, she earned enough by working in the hop fields near her home to further her education. She received a year’s training at Clinton in Oneida County, New York, under the most adverse circumstances of ill health and lack of funds.

Career in Education

Myrtilla Miner then taught at various schools, including the Clover Street Seminary in Rochester, New York and Newton Female Institute (1846-47) in Whitesville, Mississippi. There she learned through horrible experiences the evils of slavery, boldly protesting against the cruelties of the slaveholders.

When she innocently requested permission to teach the slaves of the planter whose daughters she was then tutoring, she was told that teaching slaves was a crime in Mississippi. That experience awakened in Miner a determination to return to the North and found a school for girls of color.

Normal School for Colored Girls

With the support of prominent Quaker Reverend Henry Ward Beecher and a contribution of $100 from a Quaker philanthropist, Miner was encouraged to open a school for African American girls in Washington, DC in 1851. This was only a year after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, when freedmen and runaways were beaten, bound and cast into prison and abolitionists were incarcerated for their anti-slavery activities.

The lot of the 8000 free people of color in the District of Columbia was little better than that of its 3000 slaves. The former, though legally free, in actual life had few rights. They were not admitted to public institutions, could not attend the city schools, could not testify against a white man in court, and could not travel without a pass without running the risk of being arrested and imprisoned.

District of Columbia Mayor Walter Lenox argued against the school in an article in the National Intelligencer, stating that it was

not humane to the colored population, for us to permit a degree of instruction so far beyond their political and social condition… With this superior education there will come no removal of the present disabilities, no new sources of employment equal to their mental culture; and hence there will be a restless population, less disposed than ever to fill that position in society which is allotted to them.

Despite all that, on December 6, 1851, in a rented room about fourteen feet square, in a frame house then owned and occupied as a dwelling by African American Edward Younger, Myrtilla Miner with six pupils established the Normal School for Colored Girls, the first normal school in the District of Columbia and the fourth one in the United States.

Although the school offered primary schooling and classes in domestic skills, its emphasis from the outset was on training teachers. The curriculum included history, philosophy, geography, literature, and astronomy, as well as classes in domestic skills, hygiene, and a science curriculum built around the study of nature. Each student was assigned her own garden plot to tend.

Although often in frail health, Miner was a fierce advocate and an energetic fundraiser for her school. Early financial support came from Reverend Beecher, his cousin author Harriet Beecher Stowe [link] – who gave $1000 of her Uncle Tom’s Cabin royalties – and Dr. Gamaliel Bailey, editor of the abolitionist newspaper The National Era.

Despite hostility from a portion of the community, the school prospered, but was forced to move several times in its first few years. Within two months of its opening the enrollment grew from 6 to 40, and Miner moved her students into another residence with a larger accomodations. Threats from white neighbors to set fire to the house forced Miner to leave after only one month.

With aid from her supporters, Miner was finally able to purchase a three-acre lot with house and barn on the edge of the city. Though the environment of this new home was most pleasing, the enmity of the white hoodlums still followed her. Miner and her pupils were frequently assaulted with stones and other missiles. Once threatened by mob violence, she shouted:

Mob my school! You dare not! If you tear it down over my head I shall get another house. There is no law to prevent my teaching these people and I shall teach them even unto death!

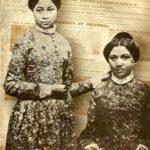

Around this time, Emily Edmonson enrolled in the school. To help protect the school and those involved with it, the Edmonson family took up residence on the grounds and both Emily and Myrtilla Miner learned to shoot a revolver.

In 1856 the school came under the care of a board of trustees, among whom were Beecher and wealthy Quaker Johns Hopkins. Myrtilla Miner guided the school through its fruitful early years but had to curtail her activities because of failing health. In 1857, Emily Howland took over leadership of the school. By 1858 six former students were teaching in schools of their own.

In 1860 the school had to be closed, and the following year Miner went to California in an attempt to regain her health. On March 3, 1863, the U.S. Senate granted the Colored Girls School a charter as the Institution for the Education of Colored Youth and named Henry Addison, John C. Underwood, George C. Abbott, William H. Channing, Nancy M. Johnson and Myrtella Miner as directors.

Miner remained three years in California in search of renewed energy and more funds for the fulfillment of her plans. Though she returned to Washington, DC in 1864, she was never able to return to the school when it reopened.

Myrtilla Miner died from injuries sustained in a carriage accident on December 17, 1864, at age 49.

The Institution for the Education of Colored Youth opened after the Civil War. From 1871 to 1876 it was associated with Howard University, its near neighbor. In 1879 it became part of the DC public school system in 1879 and was re-named Miner Normal School. In 1924 it moved into a grand new building designed by Leon E. Dessez and Snowden Ashford, which still serves as the School of Education at Howard University. A plaque on the front honors Myrtilla Miner.

In 1929 an act of Congress accredited the institution as Miner Teachers College, a major source of African American teachers employed by the District of Columbia public school system. According to historian Constance Green, the school offered “a better education than that available to most white children.”

In 1955 the school merged with Wilson Teachers College to form the District of Columbia Teachers College, and was later incorporated with other institutions to form the University of the District of Columbia in 1976. Thousands of young people have been inspired by the high standards instilled by the indomitable Myrtilla Miner and the African American educators who followed in her footsteps.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Myrtilla Miner

Encyclopedia Britannica: Myrtilla Miner

Miner Teacher’s College, Howard University

Project Gutenberg’s The Journal of Negro History

Wikipedia: Normal School for Colored Girls