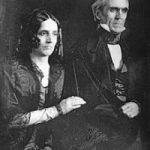

11th First Lady of the United States

Julia Tyler (1820–1889), the beautiful daughter of a prominent New York family, quickly became the darling of Washington society. Congressmen wooed her, but it was the widowed President John Tyler, thirty years her senior, who won her hand in marriage. Beginning at age 23 Julia Tyler served as First Lady of the United States from June 26, 1844, to March 4, 1845, captivating Americans with her beauty, gaiety, and love of public adulation.

Childhood and Early Years

Julia Gardiner was born on July 29, 1820 on Gardiner’s Island – a 3000-acre island off the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. She was the daughter of Juliana McLachlan Gardiner and David Gardiner, a prominent landowner and New York State Senator from 1824 to 1828. The family soon returned to their East Hampton home on Long Island when the Gardiner’s Island farm proved unprofitable.

Julia’s two brothers were sent away to school, while Julia and her sister were educated at home, but Julia did attend a boarding school in New York City for two years. There she received a smattering of literature and languages but also entered the exciting world of parties, high fashion and young male admirers, making her debut at age 15.

Julia finished school at age 17 and returned home. For the next several years she unsuccessfully urged her mother to take a house in the city to let her resume her life in society. Sometime in 1839 Julia secretly arranged to pose for an engraving that was used in a mass-produced lithograph advertisement for the dry-goods and clothing emporium Bogert & Mecamly, on lower Ninth Avenue in New York City.

This public exposure was considered humiliating to her parents and in reaction they took Julia and her sister Margaret for a tour of Europe from October 1840 through September 1841. Upon their return Mrs. Gardiner decided that if Julia was still society minded then she should be exposed to Washington society, not New York.

From January through the end of February 1842, the Gardiner family lived in Washington, DC for the social season. The small, dark-haired Julia charmed Washington society, and soon she had several high placed admirers including a Supreme Court justice.

At a White House reception, Julia was introduced to President John Tyler and his two official hostesses, his daughter Letitia Tyler Semple and daughter-in-law Priscilla Cooper Tyler. The President’s wife, Letitia Tyler, had been paralyzed by a stroke several years earlier and was unable to fill the role of First Lady.

The Gardiners returned to Washington for the winter 1842-1843 social season. Early in 1843, Julia again met President Tyler at a card party at the White House. Letitia Tyler had died the previous September, leaving seven children, the youngest an 11 year old boy still at home. Although he had been widowed only five months, the president’s affection for Julia was obvious.

Tyler proposed marriage to Julia on February 22, 1843 at the Washington’s Birthday Ball, a costume ball where she was dressed as a Greek maiden. “I had never thought of love,” Julia later said, “so I said, ‘no, no, no’ and shook my head with each word, which flung the tassel of my Greek cap into his face with every move…” When Julia told her mother about the president’s interest in her, Mrs. Gardiner took Julia back to New York. However, Julia and the president soon began a romantic correspondence.

The Gardiners again traveled to Washington for a third consecutive social season in 1844. Julia, her sister Margaret and her father David joined President Tyler and his Cabinet on a ceremonial cruise down the Potomac River aboard the newly built steam frigate USS Princeton on February 28, 1844. Aboard the ship were 400 guests, including social figures like the former First Lady Dolley Madison.

During the outing, “The Peacemaker,” the world’s largest naval gun, was ceremoniously fired several times, to the delight of the passengers. The gun then inexplicably exploded, instantly killing a number of people, including Tyler’s Secretary of State and Secretary of the Navy, and David Gardiner.

President Tyler took care of Julia, who fainted at the news of her father’s death, and comforted her in her grief over her father. Julia commented, “After I lost my father, I felt differently toward the President. He seemed… to be more agreeable… than any younger man.” Before Julia returned with her father’s remains to East Hampton, Tyler had won her consent to a secret engagement.

Marriage and Family

Because of the circumstances surrounding her father’s death, the couple agreed to marry with a minimum of celebration. Thus on June 26, 1844, the president slipped into New York City, where the wedding was performed at the Church of the Ascension. The bride’s sister Margaret and brother Alexander were bridesmaid and best man. Tyler, the first President to marry while in office, was 54 years old; Julia only 23.

The Gardiner family’s mourning was given as the reason for the ‘elopement.’ Only the president’s son, John Tyler III, represented the groom’s family. There were only twelve guests, including the President’s son John. Tyler was so concerned about maintaining secrecy that he did not confide his plans to the rest of his children. Although his sons readily accepted the sudden union, the Tyler daughters were shocked and hurt.

After the ceremony, there was a wedding breakfast at the Gardiner home, followed by a ferryboat cruise, with various naval salutes in New York Harbor. The couple debarked at Jersey City, where they took a train to Philadelphia. Both there, and in Baltimore, the new bride was the object of enormous public fascination, turning out crowds of thousands to glimpse her. A two-hour White House wedding reception was held on June 28, 1844 in the Blue Room.

The couple then proceeded on July 4, 1844 to Old Point Comfort at the federal Fortress Monroe, near Norfolk, Virginia, where a honeymoon cottage had been outfitted for them. Finally, two days later, they went to the President’s new plantation home, Sherwood Forest, in Charles City County, Virginia for several days before returning to Old Point Comfort. They returned to Washington in early August.

The news of the marriage was then broken to the American people, who greeted it with keen interest, much publicity and some criticism about the couple’s age difference. It was awkward for the eldest Tyler daughter, Mary, to adjust to a new stepmother five years younger than herself. Daughter Letitia never made peace with the new Mrs. Tyler.

First Lady of the United States

At age 24, Julia Gardiner Tyler served as First Lady from June 26, 1844 through March 4, 1845. She viewed her position to be larger than that of hostess of social events within the mansion, which had been the traditional function of that role. Since the President had no intention of seeking another term, she knew early on that her time in that role would be brief.

During this short time Julia Tyler created a number of firsts for the role of First Lady. She was the first to sit for her photograph; however, it was not mass-produced and publicly sold, as were those of her successors Abigail Fillmore, Harriet Lane and Mary Todd Lincoln. She did permit an engraving to be made of her that was inscribed with the title The President’s Bride, then mass produced and sold commercially.

She is the first known First Lady to hire a press agent and to overtly seek newspaper coverage that reported not only of her social events but articles that intended to personally raise and maintain her as a public figure. In many respects, she was the first to earn the status of the modern equivalent of celebrity, a woman whose name, face and legend were widely known in her time.

Julia Tyler has also been credited with directing the Marine Band to always play a specific march whenever she and the President entered a public event, later to be known as Hail to the Chief. It is difficult to find documented evidence of this and the innovation is sometimes credited to her immediate successor Sarah Polk.

This was a First Lady who intended to be noticed. She drove a regal coach with eight matching white Arabian horses, she dressed in lavish clothing and costumes, and wherever she went she was accompanied by 12 maids of honor, six on each side, all dressed alike. All of this was provided not through any public federal funds but the great wealth of her family.

Julia also accelerated the pace of entertaining during the four months of the last social season of the Tyler Administration – December 1844 through March 1845. She was the first White House hostess to dance at a White House party, after convincing her husband that dancing was not immoral.

On February 18, 1845, Julia Gardiner Tyler hosted a ‘Grand Finale Ball,’ for 3000 invited guests. The First Lady, dressed lavishly in a long-trained gown and a peacock-feathered headdress, sat on a platform with her maids of honor to receive formally announced guests. Some 1000 candles were said to have been burned and 96 bottles of champagne consumed, with numerous bands providing continuous dance music.

After the White House

At the end of the Tyler presidency in March 1845, John and Julia Tyler retired to Sherwood Forest in Charles City County, Virginia, where they lived tranquilly until the Civil War. There Julia gave birth to seven children in fourteen years:

• David Gardiner Tyler (1846–1927)

• John “Alex” Alexander Tyler (1848–1883)

• Julia Gardiner Tyler Spencer (1849–1871)

• Lachlan Gardiner Tyler (1851–1902)

• Lyon Gardiner Tyler (1853–1935)

• Robert “Fitz” Fitzwalter Tyler (1856–1927)

• Pearl Tyler Ellis (1860–1947)

Julia Tyler did not return to Washington, DC until February 1861, when John Tyler served as sponsor and chairman of the Virginia Peace Convention, a last-ditch effort to avoid civil war. When the convention’s proposals were rejected by Congress, Tyler saw secession as the only option, predicting that a clean split of all Southern states would not result in war.

The Civil War

Julia supported her husband’s views and defended states’ rights and the right to own slaves. When war ultimately broke out, she and her husband unhesitatingly sided with the Confederacy. John was elected to the House of Representatives of the Confederate Congress. On January 5, 1862, he left for Richmond, Virginia, but fell ill before taking his seat in the Congress.

Former President John Tyler died on January 18, 1862, which came as a severe blow to Julia, now a widow at age 41. His coffin was covered with a Confederate flag, and he was painted as a hero to the Confederacy. His funeral was attended by Confederate President Jefferson Davis and other Confederate officials.

Fearing retaliation from the north for her views, Julia collected the family papers and took them to a Richmond bank for safe-keeping. This turned out to be a mistake – during the war the bank was destroyed and the papers lost. Despite her sectional loyalty, the widowed ex-president’s wife was occasionally permitted to pass through the lines.

Battles raged throughout Virginia and Julia finally fled to the Gardiner-Tyler House – the Staten Island, New York home of her late mother. There she devoted herself to volunteer work for the Confederacy, which strained relations with her family. However, the defeat of the South left her without money or means of support and her plantation, Sherwood Forest, had been virtually destroyed. She spent many years attempting Federal reimbursement for the damage, but her legal expenses and extravagant living kept her financially limited.

Late Years

Ignoring the humiliation that many Confederates felt in the immediate post-war years, Julia Tyler resumed residency in Washington, DC in January 1872. She moved into a rental apartment on Fayette Street in the Georgetown section. She made numerous visits back to the White House during the Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant administrations, receiving considerable publicity during her March 1872 visit to Julia Grant.

Julia donated her portrait to its collection and for display at the White House. Titling herself ‘Mrs. Ex-President Tyler,’ Julia was allowed to help receive guests in a place of honor at receptions hosted by some of her successors, including Lucy Hayes and Rose Cleveland, and she maintained a correspondence with Lucretia Garfield.

In matching the conscious effort she made as First Lady to create a highly visible public profile, as a former First Lady she sought to ensure her place in history by providing biographical information to Laura Holloway, who authored the first comprehensive collective biographies of First Ladies to that time.

During a period of financial and emotional instability, Julia Tyler sought and found refuge in the Catholic Church. She converted to the faith and insisted on a second baptism, which occurred in May 1872. Her decision led many women in the country to write her for advice on how they might find the emotional support which the former First Lady declared that the conversion had provided for her.

Julia Tyler left Washington in the spring of 1876 due to severe financial hardship and returned to Sherwood Forest which had been partially restored. The estate was ordered to be sold by a court to pay a Bank of Virginia judgment against the Tyler estate – only the unexpected sale of another property kept it in the family.

Thereafter Julia used the estate as the base for annual summer visits from her children and growing number of grandchildren. By the end of the decade, however, her eldest son David ‘Gardy’ Gardiner was the full-time resident, manager and eventually owner.

Mary Todd Lincoln had received the presidential widow’s pension in 1870, and Mrs. Tyler believed she would soon be awarded the same amount of $3000. Her letter-writing and visits to Washington did not prove hopeful for another ten years. In 1880, however, she was advised that even though Congress was now likely to award her a pension, the decision could create a backlash from those who still resented granting federal funds to a former Confederate. In 1881 Julia was granted a $1200 pension.

When Lucretia Garfield was widowed upon President Garfield’s assassination later that year, however, all four living presidential widows (Tyler, Polk, Lincoln and Garfield) were awarded the same annual amount of $5000 in March 1882. Mrs. Tyler soon proposed in an anonymously published letter to the Washington Post that the amount should be raised to $10,000.

In late 1882, Julia Tyler leased a home in Richmond, Virginia, and later moved to a house across the street from her Catholic parish, St. Peter’s Cathedral. She continued to visit her son in Washington, however, in the winter social seasons until 1887.

Living out her last years comfortably in Richmond, Julia Tyler died there on July 10, 1889 at age 69, and was buried at her husband’s side in Hollywood Cemetery.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Julia Gardiner Tyler

First Lady Biography: Julia Tyler

Our First Ladies: Julia Gardiner Tyler

History’s Women: Julia Gardiner Tyler