Wife of Author Edgar Allan Poe

Virginia Clemm (1822-1847) was the wife of poet and author Edgar Allan Poe, who was best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre. They were first cousins who married when Virginia was 13 and Poe was 27. Poe’s love for Virginia Clemm was as constant as his often self-destructive determination to work in nineteenth-century America as a professional writer.

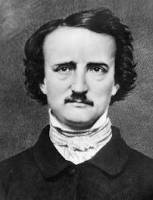

Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) was one of the earliest practitioners of the short story, and is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre, and is credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction. He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career.

Virginia Eliza Clemm was born in 1822 in Baltimore, Maryland. Her father William Clemm, Jr., a hardware merchant, had married her mother Maria Poe after the death of his first wife, Maria’s first cousin Harriet. Clemm had five children from his previous marriage and went on to have three more with Maria.

After William Clemm’s death in 1826, he left very little to the family and relatives offered no financial support because they had opposed the marriage. Maria supported the family by sewing and taking in boarders, aided with an annual $240 pension granted to her mother Elizabeth Cairnes Poe, who was paralyzed and bedridden. Elizabeth received this pension on behalf of her late husband, who was instrumental in pushing the Tories – British sympathizers – out of Baltimore during the American Revolution.

Virginia Clemm first met her first cousin Edgar Allan Poe in August 1829, four months after his discharge from the Army. She was seven at the time. In 1832, Virginia’s family – her grandmother (and Edgar’s) Elizabeth Cairnes Poe, her mother Maria and her brother Henry – rented a home in Baltimore. Poe’s older brother, who had been living with the family since he was a boy, had died from advanced tuberculosis on August 1, 1831.

Poe joined this impoverished household in 1832, and it provided him with a base of security from which he could pursue his literary career up and down the Atlantic coast. He was soon smitten by a neighbor named Mary Devereaux, and young Virginia served as a messenger between the two. Elizabeth Cairnes Poe died on July 7, 1835, making the family’s financial situation even more difficult. Henry also died around this time, leaving Virginia as Maria’s only surviving child.

Just when Edgar Allan Poe developed a romantic interest in Virginia Clemm is uncertain but by the time he moved to Richmond, Virginia in 1835 to take a job with the Southern Literary Messenger he was, with encouragement from her mother and despite her youth, considering marrying Virginia. Poe wrote to his Aunt Maria offering to support the family if they moved to Richmond.

Love and Marriage

On May 16, 1836, the 27-year-old Poe married 13-year-old Virginia Clemm (though her age was listed as 21) at the boarding house where Virginia, her mother and Poe were living in Richmond. While it was not particularly unusual for first cousins to marry at that time, Virginia was a bit on the young side.

Feeling alone in the world since the death of his parents when he was only a toddler, Poe was devoted to his child bride. He took charge of her education, personally tutoring her in the classics and mathematics. She excelled during singing and piano lessons, developing a beautiful voice.

She referred to him as ‘Eddy’ and he called her ‘Sissy.’ It has been suggested that the couple may never have consummated their marriage. Poe biographer Joseph Wood Krutch suggests that Poe did not need women “in the way that normal men need them,” and was never interested in women sexually. Friends indicated that the couple did not share a bed until Virginia turned 16, then enjoyed a normal married life.

Now Poe had to support his little family – he, Virginia and Maria. They struggled together as Poe did his best to make a living as a writer (at a time when it was nearly impossible to do so). They were forced to move several times due to Poe’s struggle for financial success, as his employment took them to several cities.

By 1836, Poe had published three volumes of poetry and won first prize for his story “Ms. Found in a Bottle.” As editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, his boss Thomas Willis White paid him a salary of $800 a year. Poe became dissatisfied with his salary but White had his own troubles. Subsequently Poe ‘retired’ from his job.

Poe was the first American determined to live his life as a professional writer. He succeeded, although it all but doomed him and his dependents to a life of relentless poverty. Most of 1837 and half of 1838 found Poe and his family struggling in New York, with little documentary evidence to shed much light on that period in their lives.

Virginia’s Illness

In mid-1838 the Poes moved to Philadelphia, where there was a long, uninterrupted stretch between early 1838 and the spring of 1844 that was a period of heightened creativity and domestic tranquility for Poe. At home – in each of the five houses they rented during this time – were Virginia, Maria and their beloved cat, Caterina.

Life had settled into a daily round of contented housekeeping and writing in the evenings, after Poe returned from his day job. Poe celebrated their stability by buying some more expensive furnishings, including a piano and a harp for Virginia.

On January 20, 1842, Virginia was playing the piano and singing when she began to cough and blood poured from her mouth. This pulmonary hemorrhaging was a symtom of tuberculosis (then called consumption), a disease which had already killed so many of Edgar’s loved ones.

They moved several times while in Philadelphia and in their last home there, in Spring Garden, Virginia was well enough to tend the flower garden and entertain visitors by playing the harp or the piano and singing. Novelist, Captain Mayne Reid wrote of his friendship with Poe and Virginia there:

In this humble domicile I can say that I have spent some of the pleasantest hours of my life – certainly some of the most intellectual. They were passed in the company of the poet himself and his wife – a lady angelically beautiful in person and not less beautiful in spirit. No one who remembers that dark-eyed, dark-haired daughter of Virginia – her own name, if I rightly remember – her grace, her facial beauty, her demeanor, so modest as to be remarkable – no one who has ever spent an hour in her company but will endorse what I have said above. I remember how we, the friends of the poet, used to talk of her high qualities. And when we talked of her beauty, I well knew that the rose-tint upon her cheek was too bright, too pure to be of Earth. It was consumption’s color – that sadly-beautiful light which beckons to an early tomb.

The Poe family next moved to New York City sometime in early April 1844, traveling by train and steamboat. Virginia waited on board the ship while her husband secured space at a boarding house on Greenwich Street. Poe began to drink more heavily under the stress of Virginia’s illness. He worked first at the Evening Mirror, where his poem, “The Raven,” was published on January 29, 1845. It was an instant success and made Poe a household name, though he was paid only $9 for its publication.

Edgar Allan Poe became associate editor of the Broadway Journal in February 1845, and the following month, editor and part owner. There he alienated himself from other writers with his biting literary criticism in that paper, going so far as to accuse Henry Wadsworth Longfellow of plagiarism, though Longfellow never responded.

The Scandal

After the publication of “The Raven” in 1845, Poe promptly became popular at New York’s literary salons, where the poet Fanny Osgood – frail, dark-haired, and a consummate flirt – was a rising star. Poe attracted her interest with a public compliment during a lecture about the terrible state of American poetry, he singled her out as a rare exception.

Their subsequent meeting set off a flurry of somewhat sappy poems; many were published under pen names, but the writers’ identities were thinly veiled, and the city’s literary ladies gossiped that Poe and Osgood were carrying on a semi-public courtship. The issue was that they both were married, Fanny to portrait painter Samuel Osgood, from whom she was estranged.

Now 23, Virginia Clemm Poe, now housebound with tuberculosis, was aware of the friendship and might have actually encouraged it, seeing something in Osgood that was worthwhile for her literary husband. She often invited Osgood to visit them at home, believing that the older woman had a “restraining” effect on Poe, who had made a promise to “give up the use of stimulants” and was never drunk in Osgood’s presence. And Poe shared all of Osgood’s letters with Virginia and Maria.

At the same time another poet and writer, Elizabeth Ellet, became enamored of Poe and jealous of Osgood. Though Poe called Ellet’s love for him “loathsome” and wrote that he “could do nothing but repel [it] with scorn,” he printed many of her poems to him in the Broadway Journal while he was the editor. But he did not respond to her advances.

Ellet undertook a smear campaign, careful to see that the innuendoes about his relationship with her perceived rival Fanny Osgood reached Virginia’s ears, even going so far as to write anonymous, vindictive letters to Virginia. Although the rumors upset Virginia, she never doubted her husband. During a visit to the Poe house, Ellet read a letter from Osgood to Poe filled with, she claimed, “fearful paragraphs.”

Ellet took this incriminating information straight to Fanny Osgood, who was already worried about her reputation in light of a new development – she was pregnant. Osgood then sent her Margaret Fuller and Anne Lynch Botta to ask Poe to return the letters. Angered by their interference, Poe called them “Busy-bodies” and said that Ellet had better “look after her own letters,” suggesting indiscretion on her part. He then gathered up the letters Ellet had written to him and left them at her house.

Osgood’s husband stepped in and threatened to sue Ellet unless she formally apologized for her insinuations. She retracted her statements in a letter to Osgood saying, “The letter shown me by Mrs. Poe must have been a forgery.” She put all the blame on Poe, and spread rumors that he was insane, which was even reported in newspapers.

For Poe, the result was disastrous. His reputation was tainted and he was excluded from the New York literary salons. Although Poe and Osgood never saw each other after 1847, his relationship with her – which he called an amour – is generally considered a meaningful one. The rejected Ellet persisted in her attacks on Poe until his death.

The affair was resolved in a manner appropriate to the time – within four years the three main parties were dead. Shortly before his death, Poe was still scarred enough by the experience to describe literary women as “a heartless, unnatural, venomous, dishonorable set, with no guiding principle but inordinate self-esteem.” (The one exception, he added, was Fanny Osgood.)

At Poe Cottage

In May 1846 Poe moved Virginia and Maria to their final home which still stands in Fordham, The Bronx, about fourteen miles outside New York City – their final home. The cottage was small and simple: it had on its first floor a sitting room and kitchen and its unheated second floor had a bedroom and a study. It is known today as Poe Cottage.

Virginia was by this point an invalid, and Poe was chronically broke but provided as well as he could and despite the scandals involving his attention to other women no one doubted his devotion to his wife. Poe became a workaholic, churning out stories, poems, essays, reviews, whatever he could get, to pay the bills and try to keep Virginia healthy.

By November of that year, Virginia’s condition was hopeless. Her symptoms included irregular appetite, flushed cheeks, unstable pulse, night sweats, high fever, sudden chills, shortness of breath, chest pains, coughing and spitting up blood.

Of the recent failure of the Broadway Journal, the only magazine Poe ever owned, he said, “I should have lost my courage but for you – my darling little wife – you are my greatest and only stimulus now to battle with this uncongenial, unsatisfactory and ungrateful life.”

As Virginia was dying, the family received many visitors. Family friend Elizabeth Oakes Smith said that Virginia admitted, “I know I shall die soon; I know I can’t get well; but I want to be as happy as possible, and make Edgar happy.” She promised her husband that after her death she would be his guardian angel.

Virginia was tended to for a time by friend 25-year-old Marie Louise Shew, who had learned medical care from her father and her husband, both doctors. She provided Virginia with a comforter as her only other cover was Poe’s old military cloak, as well as bottles of wine, which the invalid drank “smiling, even when difficult to get it down.”

On January 29, 1847, Poe wrote to Shew:

Kindest – dearest friend – My poor Virginia still lives, although failing fast and now suffering much pain. May God grant her life until she sees you and thanks you once again! Her bosom is full to overflowing – like my own – with a boundless – inexpressible gratitude to you. Lest she may never see you more – she bids me say that she sends you her sweetest kiss of love and will die blessing you. But come – oh come tomorrow!

Virginia Clemm Poe died the following day, January 30, 1847 at age 24 in the cottage’s first floor bedroom. Poe literally collapsed at Virginia’s bedside the moment she stopped breathing. Not surprisingly, he became sick for months, suffering from depression and an irregular heartbeat. A friend said of him, “the loss of his wife was a sad blow to him. He did not seem to care, after she was gone, whether he lived an hour, a day, a week or a year…”

Marie Louise Shew helped in organizing Virginia’s funeral, even dressing her in fine linen and purchasing the coffin. Death notices appeared in several newspapers, including the New York Daily Tribune and the Herald. The funeral was February 2, 1847. Attendees included editor Nathaniel Parker Willis and writer Ann Stephens.

Poe regularly visited Virginia’s grave. As his friend Charles Chauncey Burr wrote, “Many times, after the death of his beloved wife, was he found at the dead hour of a winter night, sitting beside her tomb almost frozen in the snow.” Virginia’s remains were later placed beside her husband’s in Westminster Hall and Burying Ground in Baltimore, Maryland.

On January 4, 1848, Poe wrote to friend George Eveleth:

Six years ago, a wife, whom I loved as no man ever loved before, ruptured a blood vessel in singing. Her life was despaired of. I took leave of her forever and underwent all the agonies of her death. She recovered partially and I again hoped…

At the end of a year the vessel broke again. I went through precisely the same scene. Again in about a year afterward. Then again – again – again and even once again at varying intervals.

Each time I felt all the agonies of her death – and at each accession of the disorder I loved her more dearly and clung to her life with more desperate pertinacity. But I am constitutionally sensitive – nervous in a very unusual degree. I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.

During these fits of absolute unconsciousness I drank, God only knows how often or how much. As a matter of course, my enemies referred the insanity to the drink rather than the drink to the insanity. I had indeed, nearly abandoned all hope of a permanent cure when I found one in the leash of my wife.

This I can and do endure as becomes a man – it was the horrible never-ending oscillation between hope and despair which I could not longer have endured with the total loss of reason. In the death of what was my life, then, I receive a new but – oh God! how melancholy an existence.

Shortly after Virginia’s death, Poe courted several other women, but established no lasting relationships. Frances Sargent Osgood, whom Poe also attempted to woo at that time, believed “that [Virginia] was the only woman whom he ever loved.” (Osgood herself died of tuberculosis in 1850.)

On October 7, 1849, at age 40, Edgar Allan Poe died alone after collapsing at a tavern in Baltimore, without ever achieving an ongoing, loving connection with another woman; just as the married narrators of his tales are never able to attain lasting relationships with their brides.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Edgar Allan Poe

Death of Virginia Clemm Poe

Wikipedia: Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe

At one point in this article, it says “Feeling alone in the world since the death of his parents when he was only a toddler”. It should say that his father left him then his mother died when he was a toddler. I just thought it would be good to correct it.