Slave Freed by Abolitionists in Philadelphia

Jane Johnson (1820-1872) was a slave whose escape to freedom was the focus of precedent-setting legal cases in 19th century Philadelphia. Safeguarded by Philadelphia abolitionists after her escape in 1855, Johnson later settled in Boston. There she married, and sheltered other fugitives slaves. Her son Isaiah served in the American Civil War with the 55th Massachusetts Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops.

Jane Johnson is believed to have been born into slavery as Jane Williams in or near Washington, DC, the daughter of John and Jane Williams; the exact year of her birth is unknown. Virtually nothing is known of her early life, which she presumably spent on Virginia plantations; it is believed that she lived for part of that time in Caroline County and had several owners.

She is presumed to have married a fellow slave surnamed Johnson about 1843; with him she apparently had three sons, one of whom was sold away to an unknown master. At the beginning of 1854 Johnson and her remaining two sons were sold by her master, Cornelius Crew, a plantation owner in Richmond, Virginia to John Hill Wheeler, a prominent North Carolina slaveholder.

Background

Pennsylvania passed a gradual abolition statute in 1780, which did not free any existing slaves, but banned the slave trade in Pennsylvania and freed the children of slaves born after the law was passed once they reached a certain age. Thereafter Philadelphia had become a mecca for free blacks in America.

Throughout the early 1800s, a steady stream of black migrants hoping to escape slavery fled into the Pennsylvania counties just north of the Maryland border. By 1820 the city’s black population was nearly eleven percent. As the African American population grew, so did white hostility towards them. African Americans were attacked and killed in the street and in their houses during a race riot in 1834.

The network now generally known as the Underground Railroad was formed in the early 19th century, and reached its height between 1850 and 1860. It was an informal but very effective network of abolitionists, secret routes and safe houses used by slaves to escape to free states and Canada.

Aiding runaways became significantly more difficult, however, after the passage of the federal Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, which compelled northern citizens to assist in the apprehension and return of fugitive slaves back to their southern masters, and threatened those who assisted escaped slaves with prosecution and imprisonment.

The Escape

In July 1855, John Wheeler and his family traveled by train from Washington to Philadelphia. After a short visit with relatives, they planned to travel by ferry to New York City, then by ship to Central America, where Wheeler was the newly-appointed U.S. minister to Nicaragua. The Wheelers were accompanied by three of their slaves: Jane Johnson, age 35, and her sons, Daniel, age 12, and Isaiah, age 7.

Unknown to Wheeler, Jane had no intention of traveling to Central America or remaining a slave. Her plan was to leave Wheeler and escape with her children to freedom as soon as they were safely in the North. News of the Underground Railroad and abolitionists who helped fugitive slaves was widespread among slaves in the upper South, particularly in urban centers like Richmond and Washington, DC.

On the morning of July 18, 1855 John Wheeler and his entourage arrived at the Broad Street Station in Philadelphia and made their way by carriage to the home of Wheeler’s father-in-law, artist Thomas Sully. After a brief visit, they continued to Bloodgood’s Hotel on the river next to the ferry that would take them to Camden and on to New York.

Wheeler left Johnson and her sons at the hotel, locking them in their room and instructing them to talk to no one until he returned later that afternoon. However, Jane informed a black hotel worker that she was a slave and wanted to be free. The worker drafted a note to William Still, the African American head of the Vigilance Committee of the local Underground Railroad, and sent it off to Still at the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society office.

In the summer of 1855, Philadelphia had the largest free black population in the country. Prominent blacks like William Still and Robert Purvis were active members and officers in the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and worked with Lucretia Mott, Passmore Williamson and other white abolitionists in the struggle against slavery. This network was put at Jane Johnson’s disposal when she made known her intention to gain her freedom.

William Still alerted Passmore Williamson at his office, and the two went to the hotel, where they found the Wheeler party at the dock, about to leave on the five o’clock ferry. The abolitionists approached the Wheeler party accompanied by five black dockworkers. Still told Jane that under Pennsylvania law she was a free woman and could leave Wheeler here and now if she wished.

Williamson explained the situation to the protesting Wheeler, who was restrained by the dockworkers. The abolitionists rushed Johnson and her sons to a waiting carriage that drove them to Still’s home in the city. It was a quick operation. “The whole affair was over and I back in my office in less that 3/4ths of an hour,” Williamson later wrote.

Under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, anyone assisting in the escape of a slave faced prosecution. Wheeler, a prominent Democrat, appealed to his friend Judge John Kane of the Federal District Court, another proslavery Democrat, who summoned Williamson before him with a writ of habeas corpus ordering him to bring Jane and her two sons before the bench.

It was the practice of the Vigilance Committee to keep such information compartmentalized; Williamson was not informed of the details of Johnson’s escape and he did not wish to know, satisfied with the news from Still that she was safe. Williamson told the judge – truthfully – that he did not know their exact whereabouts, and on July 27, 1855 he was sent to prison for contempt of court.

It was a legal stretch, using a writ of habeas corpus to imprison a man and return a woman to slavery, and championing the right of slaveholders to travel the free states with their slaves in spite of state laws banning slavery. Though couched in convoluted legalese, Kane’s decision to imprison Williamson was rooted in the commonplace racist logic of the time.

Kane even rejected an affidavit from Jane Johnson affirming there had been no abduction as immaterial and irrelevant to the proceedings. Like most Democrats of the time, Kane believed that black people, even if free, enjoyed no citizenship rights under the Constitution, and that masters should be secure in taking their slave property anywhere in the nation, a belief affirmed later in the U. S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision.

Jane Johnson’s rescue had captured the attention of the press, but Passmore Williamson’s incarceration made the episode national news. Horace Greeley’s influential New York Tribune covered the case extensively and, through its widely circulated daily and country editions, spread the story throughout the nation.

A number of prominent editors and antislavery crusaders in the North came to his defense, including William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. Antislavery weeklies covered the story in every issue. Williamson’s legal team initiated appeals, affidavits and statements regularly featured in the press.

Williamson would spend more than three months in Moyamensing Prison, literally holding court, as the northern press spread the story throughout the country. Friends comfortably furnished his cell, and he received several hundred visitors and congratulatory letters. One caller was Harriet Tubman, even then an Underground Railroad legend with a price on her head.

Jane Johnson remained an active player in this drama. She had apparently lived in a number of secret locations during July and August, and sometime during this period she stayed in New York. She spoke at several abolitionist meetings, denying that she had been abducted from Wheeler, and submitted an affidavit to Judge Kane declaring her long-standing intention to leave Wheeler as soon as an opportunity arose.

But by August 1855 Johnson was back in Philadelphia, staying at the home of abolitionist Lucretia Mott. On August 29, accompanied by Mott and some of her associates, Johnson made a surprise appearance at the trial of William Still and the five dockworkers who had restrained Wheeler on the dock; all six had been accused of assault and battery.

Johnson testified on their behalf, repeating her claim that she had not been forcibly abducted, and her dignified presence in the courtroom reportedly made a positive impression. Following Johnson’s testimony, Still and three of the men were acquitted; two others were convicted of assault but received fines of $10 and jail sentences of one week.

Johnson quickly left the courthouse followed by federal marshals determined to arrest her. State and local authorities were just as determined to protect the witness and vowed resistance. Jane’s flight from the courtroom was described in a letter by Lucretia Mott:

We didn’t drive slow coming home Miller [J. Miller McKim, chairman of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society], an officer, Jane and self – another carriage following with 4 officers for protection. Miller and the slave passed quickly through our house, up Cuthbert St. to the same carriage, who drove around to elude pursuit. They drove to Broad and Coates, where the Hallowell boys were ready to receive her with carriage and horse coach and conveyed her to Miller’s and lest she should be pursued her, he took her that evening over to Edward’s and the next day they sent her to Plymouth [Meeting] and they ventured to take her to Norristown Meeting, where she told her story well and made a good impression.

Williamson, however, remained in prison for his earlier contempt citation. As Jane Johnson settled into her new life, the events she had set in motion continued to rage in Philadelphia. In September the Pennsylvania Supreme Court affirmed Judge Kane’s action. Rumors circulated that President Franklin Pierce threatened to have Williamson placed in military custody should the court free him.

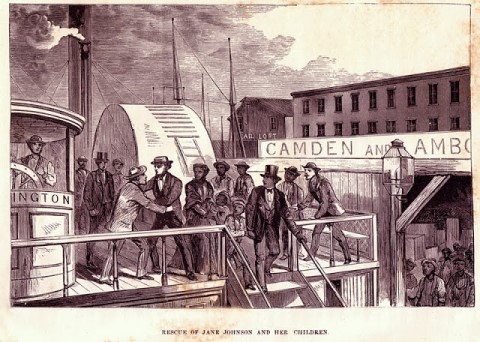

Image: Jane Johnson’s rescue from a ferry in Philadelphia

William Still, pictured in a tall top hat at the center of the image, is escorting Johnson and her children off the ferry.

Judge Kane offered to release Passmore Williamson if he would change his testimony to agree with Kane’s contention that he was the controlling party in the episode. Williamson simply repeated the statement which led to his imprisonment: that he never had custody of Wheeler’s slaves, and could not therefore produce them before the court.

Judge Kane finally relented and took the opportunity to extricate himself from the situation. After more than three months in jail, Williamson – who had become something of a national hero in the anti-slavery cause – was released on November 3, 1855. Williamson returned to his active role with the Underground Railroad, helping several hundred fugitive slaves who passed through Philadelphia in the waning years of American slavery.

And his African American colleague, William Still, secretly kept accounts of Underground Railroad activities in Philadelphia. In 1872, seven years after the end of the Civil War, Still published The Underground Railroad, telling Jane Johnson’s story and that of many others. It is the single best collection of accounts of African Americans who fled slavery in the decades before the War.

After Jane Johnson’s dramatic visit at the Still trial, she had returned to New York and later settled in Boston. In a December 3, 1855 letter to Williamson, Boston black activist William Cooper Nell informed him that in October he helped Jane find work and a place to live.

On May 26, 1856, Nell wrote:

Jane Johnson called in this morning and expressed much pleasure on hearing from you. She requested my informing you that she now lives [at] No. 1 Southack Court – and is quite well. Her boys are progressing finely at School, for all these advantages of freedom she feels heartfelt gratitude for your exertions.

In 1856 Johnson married Lawrence Woodfork, who had been born in Virginia and is assumed to have also been an escaped slave; he died five years later. In 1864 Johnson was briefly married to William Harris, a black sailor who was presumed lost at sea. Johnson’s whereabouts between 1866 and 1870 are unknown, but by 1871 she was back in Boston.

Jane Johnson died of dysentery on August 2, 1872.

Johnson came back into public view in 1995, when writer Lorene Cary made her story the subject of a novel, The Price of a Child.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Jane Johnson

Jane Johnson Historical Marker

Library Company: The Liberation of Jane Johnson

American National Biography Online: Jane Johnson