First Lady: Wife of Fifth U.S. President James Monroe

Elizabeth Kortright was born June 30, 1768, and was raised in New York City. Her mother died when Elizabeth was nine, and Hester Kortright, her paternal grandmother, raised the young girl. Hester had a reputation of being a strong and independent woman, who owned and managed her own vast real estate holdings in old Harlem. Elizabeth was considered one of the most beautiful women of her generation.

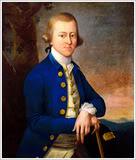

James Monroe was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on April 28, 1758, on his parents’ small plantation. He lost both parents by age 16 and inherited his father’s estate. He enrolled in William and Mary College in 1774 but when the American Revolution began he left after two years. He enlisted as a lieutenant in the 3rd Virginia Regiment, and was seriously wounded at Trenton, and his heroism earned him the rank of major.

In 1777-78 he was an aide to General William Alexander with the rank of colonel. Because of an excess of officers, Monroe returned to Virginia. He sold his small inherited Virginia plantation in 1783 to enter law and politics. He began to study law with his friend Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson, and was elected to the lower house of the legislature in 1782.

Home and Family

On February 16, 1786, at age 17, Elizabeth Kortright married James Monroe, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Continental Army and U.S. Congressman from Virginia. She was seventeen and he was twenty seven. They spent their honeymoon on Long Island and then lived in New York, the first U.S. capital, with her father. They had three children: two daughters and a son.

When Monroe left Congress in 1786, the couple returned to his native state of Virginia where he practiced law; they lived first in Fredericksburg, and then in Charlottesville to be near his close friend, Thomas Jefferson at Monticello.

With Monroe’s election to the Senate in 1790, the Monroes relocated to the new temporary capital city of Philadelphia. Elizabeth Monroe, however, spent much of her time in New York with her sisters and their families. Four years later, when Monroe was named U.S. Minister to France, they moved to Paris.

Elizabeth Monroe was immediately fond of the city and its people, and she was well-received there. During the last days of the French Revolution, Elizabeth made a name for herself by her courageous visit to the imprisoned wife of the Marquis de Lafayette – the great friend of revolutionary era patriots and France’s most prominent supporter of American independence.

Not wishing to offend their ally, the French government used Elizabeth Monroe’s “unofficial” interest in Adrienne de Lafayette to release her on January 22, 1795, without any official provocation and thus maintain their alliance with the U.S. yet save face for the imprisonment.

Recognizing the importance placed on social behavior and appearance, Elizabeth Monroe’s adoption of French clothing combined with her physical beauty earned her the name ‘La Belle Americane.’ By their dignified manner, and through the relationships built by the Monroes, many foreign nations came to accept the establishment of the United States as not only a new nation, but a powerful and sophisticated one that was carrying out the principals of democracy.

The Monroes secured the freedom of American writer Thomas Paine from prison (for opposing the execution of King Louis XVI). However, Paine’s attacks on President Washington for letting him languish in prison so long, combined with Monroe’s lavish praise of France (in contradiction of Washington’s neutrality policy) led to his recall and the Monroes returned to Virginia.

For 17 years Monroe, his wife at his side, alternated between foreign missions and service as governor or legislator of Virginia. They made Oak Hill plantation their home after he inherited it from an uncle. While Monroe was Governor of Virginia (1799-1803), Elizabeth developed serious health problems. The symptoms suggest that it was a type of epilepsy that in later years frequently left her shaking and falling into unconsciousness.

While Monroe served as Secretary of State (1811-1817) under Madison, the Monroes purchased a private home in nearby Loudoun County, Virginia, and spent little time in the capital. Elizabeth was rarely seen other than official functions and did not return social visits that were made to her by other spouses of officials.

First Lady 1817 – 1825

Elizabeth Monroe was 48 years old when her husband became president, and was First Lady for eight years. Despite her age, she looked youthful. Through much of the administration, however, she was in poor health and curtailed her activities.

Repairs to the White House from damage sustained when the British set fire in 1814 were not yet completed, and the public reception following the new President’s swearing-in ceremony were held in the Monroe’s private home on I Street. However, Mrs. Monroe did not appear at either the swearing-in ceremony nor greet guests at the reception in her home.

Elizabeth Monroe provided an extreme contrast to her predecessor, the highly popular Dolley Madison, who had conceived of her role as partially a public one. As a consequence of both her fragile health and reserved social nature, as well as the prestige she hoped to convey by limiting the access of the President’s wife to the spouses of other officials, Elizabeth Monroe established a less democratic protocol and was dubbed a snob.

Elizabeth held firm and on January 22, 1818, as she began her first winter social season as First Lady. Intended to increase the prestige of the Executive branch, however, it initially backfired. When the Monroes decided to leave Washington for their nearby Virginia home instead of hosting the annual open house public reception on Independence Day in 1819, even those citizens not among the city’s elite were insulted.

Through the second Monroe Administration, a rare time during which there was a sustained period of none of the partisanship that always marked political life in Washington, Elizabeth Monroe’s policy was accepted and guests returned to the White House. It also marked her slow withdrawal from the First Lady role.

When Elizabeth did appear at receptions and other public events, she looked youthful and capable. The White House did not release any information concerning her health condition; had it been known that she suffered from epilepsy there might have been understanding. Ignorance regarding epilepsy at the time, however, led to widespread belief that it was a form of mental illness, making it even more unlikely that they would disclose the details.

A guest at the Monroes’ last social event, on New Year’s Day in 1825, described the First Lady as “regal-looking” and noted:

Her dress was superb black velvet; neck and arms bare and beautifully formed; her hair in puffs and dressed high on the head and ornamented with white ostrich plumes; around her neck an elegant pearl necklace. Though no longer young, she is still a very handsome woman.

Elizabeth Kortright Monroe dramatically reduced the social obligations of future First Ladies. She zealously guarded her daily schedule and her family’s privacy, even at the risk of disappointing the American public. Some social customs she developed remain a part of White House protocol.

James Monroe in Politics

In 1784 Monroe, Jefferson and Richard Henry Lee were members of the Virginia delegation to the Confederation Congress, the U.S. governing body from March 1781 through March 1789. Monroe endorsed the recommendation that a special convention be held. He was responsible for the structure of territorial government incorporated in the Ordinance of 1787. In 1786 he led the fight against the proposal of John Jay, Secretary for Foreign Affairs, to negotiate a treaty with Spain closing the Mississippi for 20 years in return for commercial concessions.

After a few years of law practice Monroe was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1790. He was critical of the of the George Washington administration because he believed they were favoring the commercial class and seeking closer ties with Great Britain. He attributed these policies to the influence of Alexander Hamilton. Monroe joined James Madison and Jefferson in organizing the opposition that developed into the Republican party.

In 1794 Washington appointed Monroe minister to France. Monroe accepted at the urging of the Republicans, who felt that friendship with France was essential to preserve the republican government in the United States. Arriving in France immediately after the downfall of Robespierre, Monroe was able to ease recent tensions, but he irritated Washington by publicly voicing enthusiasm for the French Revolution.

Relations between France and the United States worsened, and Monroe was recalled in 1796 in a manner casting doubt on his conduct. He published a vindication, asserting that the administration was seeking to join England in the war against France. As proof that Monroe’s recall had not shaken party confidence, the Republicans elected him governor of Virginia in 1799.

In 1803, after Spanish authorities had closed the Mississippi River to American ships, President Jefferson sent Monroe to France to assist Robert R. Livingston in seeking a port for America at the mouth of the river. Monroe garnered national acclaim for negotiating the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. From 1804 to 1807 he was minister to Great Britain.

In 1811 President James Madison, plagued by conflicts within his own party, appointed Monroe Secretary of State. Monroe’s entry into the Cabinet did not change the policy of commercial warfare with Great Britain, but it did strengthen the administration. He collaborated with the ‘War Hawks’ in drafting the measures that culminated in the declaration of war against England in 1812, and continued in the State Department during the war, serving simultaneously as secretary of war.

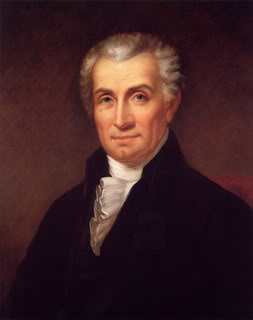

Image: President James Monroe, Circa 1824

Rembrandt Peale, Artist

Monroe was named Republican presidential candidate in 1816 and the Federalists offered only token opposition. As president of the United States, Monroe was tall, dignified and formal in manner, and was admired for his genuine goodness, warmth and lack of malice. He did not reach decisions quickly, and his attention to detail gave him a soundness of judgment. He introduced into the White House a new, more formal note.

In 1820 Monroe was unopposed, and received all the electoral votes but one. A crisis took place in 1820, following attempts to make the abolition of slavery a condition for the admission of Missouri to statehood. This conflict so divided the nation that many feared the Union would be destroyed. Monroe opposed any restriction on Missouri, but in the interest of harmony he accepted the compromise admitting Missouri as a slave state.

Monroe’s most important accomplishments were in foreign affairs. In 1819 he capitalized on Andrew Jackson’s invasion of Florida to pressure Spain into ceding Florida and establishing the western and northern boundaries of Louisiana. In 1825, Monroe retired from office esteemed highly by many, including Thomas Jefferson who once stated: “Monroe was so honest that if you turned his soul inside out there would not be a spot on it.”

Elizabeth Monroe was in such poor health that she and her husband had to remain in the White House three weeks after his Administration expired. Retired to their Oak Hill plantation estate in Virginia, her activities remained centered on her family and she assumed no public role and participated in no public activities. She traveled only to New York to visit her daughter Maria Hester Monroe Gouverneur.

Monroe’s retirement was plagued by financial difficulties. He had fulfilled his youthful dream of becoming the owner of a large plantation, but his efforts in agriculture had never been profitable, and though he owned land and slaves he was rarely on-site to oversee the operation. Therefore the slaves were treated harshly to make them more productive and the plantations barely supported themselves if at all. His lavish lifestyle had often necessitated selling property to pay debts.

Monroe obtained some financial relief when Congress voted him $30,000 in 1826, and a similar sum in 1831. In 1829, as a member of the Virginia Constitutional Convention, he joined Madison in an unsuccessful attempt to arrange a compromise between Eastern and Western interests.

In 1826, Elizabeth suffered a seizure and collapsed near an open fireplace and sustained severe burns; she only lived three years after the accident.

Elizabeth Kortright Monroe died at Oak Hill on September 23, 1830, at the age of 62. She was buried at Oak Hill, but was re-interred beside her husband at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, in 1903.

James Monroe then moved to New York City to live with their daughter Maria, and predicted that he would not live long after Elizabeth’s death; he died ten months later.

James Monroe died of heart failure and tuberculosis on July 4, 1831, in New York City, and was buried in the Marble Cemetery there. In 1858 Monroe’s remains were re-interred at the President’s Circle at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

James Monroe was considered the last president who was a Founding Father and the last from the Virginia Dynasty and Republican Generation. His presidency was marked both by an ‘Era of Good Feelings’ – a period of relatively little political strife. Monroe is most noted for his proclamation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, which stated that the United States would not tolerate further European intervention in the Americas.

Favorite James Monroe Quote:

If we look to the history of other nations, ancient or modern, we find no example of a growth so rapid, so gigantic, of a people so prosperous and happy.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: James Monroe

Wikipedia: Elizabeth Monroe

First Lady Biography: Elizabeth Monroe

The White House: Elizabeth Monroe