First Lady and Wife of Founding Father James Madison

Image: Dolley Payne Todd Madison

First Lady of the United States 1809-1817

By Rembrandt Peale c. 1817

Dolley Payne was born on May 20, 1768, in the Quaker settlement of New Garden in Guilford County, North Carolina. Her parents, John and Mary Coles Payne, had moved there from Virginia in 1765. Her mother, a Quaker, had married John Payne, a non-Quaker, in 1761. Three years later, John was admitted to the Quaker Monthly Meeting in Hanover County, Virginia, and Dolley Payne was raised in the Quaker faith.

Dolley was one of 8 children, four boys and four girls. In 1769 the family returned to Virginia. As a young girl, Dolley grew up in comfort in rural eastern Virginia. In 1783, John Payne emancipated his slaves and moved the family to Philadelphia, where he went into business as a starch merchant.

No records exist of any formal education for Dolley. Although Philadelphia’s Pine Street Meeting, to which the Paynes belonged, did offer class instructions for girls as well as boys, Dolley was 15 years old at the time she moved to Philadelphia and was past the usual age for school.

By 1789, however, Payne’s business had failed; he died in 1792. Dolley’s mother, Mary Coles Payne, initially made ends meet by opening a boarding house, and one of her guests was Congressman Aaron Burr. A year later Mary moved to western Virginia to live with her daughter Lucy, who had married George Steptoe Washington, a nephew of George Washington.

In January 1790, Dolley Payne married John Todd a lawyer and fellow Quaker. They lived in a modest three-story brick house at the corner of Fourth and Walnut Streets. Their son John Payne Todd was born in 1792 and William Temple Todd in 1793. Dolley’s eleven-year-old sister Anna, whom Dolley referred to as her “daughter-sister,” lived with the Todds as well.

During a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia in the fall of 1793, Dolley’s husband and younger son both died on the same day, leaving her a widow at the age of twenty-five.

In May 1794, James Madison, a Congressman from Virginia, asked his friend Aaron Burr to introduce him to Dolley Todd. Madison was seventeen years her senior and, at the age of forty-three, a long-standing bachelor. A courtship followed, and by August she had accepted his proposal of marriage.

On September 15, 1794, Dolley married James Madison at her sister Lucy’s home in present-day West Virginia. Following their wedding, James and Dolley honeymooned at the home of Madison’s sister, Nelly Hite, at Belle Grove near Winchester, Virginia, before returning to Philadelphia where Madison resumed his leadership duties in Congress. They lived in Madison’s elegant three-story Spruce Street brick house until his retirement from Congress in 1797.

For marrying a non-Quaker, she was expelled from the Society of Friends. This never seemed to bother the lively Dolley who later noted that the “Society used to control me entirely and debar me from so many advantages and pleasures.”

James Madison: Founding Father

James Madison was among the first to recognize that a stronger central government would be critical to the new nation’s survival. He undertook an exhaustive study of government structures throughout history, outlining reasons why earlier attempts at democracy and representative government failed. His research convinced him that the Articles would not withstand the onslaughts of state interests.

Madison’s ideas eventually crystallized into the Virginia Plan, where the interests of individuals, states, and the national authority were balanced and mixed into “an extended republic.” He also sought the counsel of influential Americans whose support was vital if any changes in the government were to take place. George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Edmund Randolph were among the prominent politicians to support Madison’s plan.

When the Constitutional Convention finally began in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787, many feared that the young country was near collapse. During the long, hot summer that followed, the 55 delegates hammered out a new framework of government. Madison lobbied strongly for his positions, proposed compromises and took copious notes.

In the end, many of Madison’s proposals were incorporated into the Constitution, including representation in Congress according to population, support for a strong national executive, the need for checks and balances among the three branches of government and the idea of a federal system that assigned certain powers to the national government and reserved others for the states.

However, the Constitution still faced challenges with the state ratification conventions. Along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, Madison wrote a series of essays, The Federalist Papers, that argued for ratification. Virginia’s support would be absolutely critical, so he lobbied his fellow citizens hard for its passage. His efforts were rewarded in June 1788, when New Hampshire and Virginia ratified the Constitution.

In 1797, after eight years in the House of Representatives, James Madison retired from politics. He took his family to Montpelier, the Madison family estate in Orange County, Virginia. There they expanded the house and settled in, expecting to remain planters and live quietly in the country. Dolley assumed not only household management of the plantation and slaves, but also cared for her elderly mother-in-law who lived there.

However, when Thomas Jefferson became the third president of the United States in 1801, he asked James Madison to serve as his Secretary of State. He accepted, and the Madison family, moved to Washington, DC, the new capital, in June 1801.

Initially, the family – consisting now of James, Dolley, son Payne and sister Anna – lived in The White House (known simply as the “president’s house” at this time) with Jefferson, but by 1802 they had their own house on F Street two blocks away. Anna would continue as part of the family until she married Congressman Richard Cutts in 1804.

At receptions and dinners President Thomas Jefferson – who had been a widow since 1782 – felt required hostess, he asked Dolley Madison to help him. Though not given an official designation, her exposure to the political and diplomatic figures who were guests of the President, as well as to the general public who came to meet him, provided her with a lengthy experience as a White House hostess.

Dolley Madison’s popularity as a hostess for Jefferson in Washington added greatly to the recognition of her husband by those members of congress whose electoral votes chose the winner of presidential races. During the 1808 election, however, there was an attempt by Federalist newspapers in Baltimore and Boston that implied Mrs. Madison had been intimate with President Jefferson as a way of attacking her character.

In the approaching 1808 presidential election, with Jefferson ready to retire, the Democratic-Republican Party nominated James Madison to succeed him. Madison was elected the fourth President of the United States, serving two terms from 1809 to 1817; Dolley became First Lady of the United States.

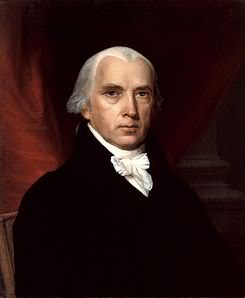

Image: President James Madison

4th President of the United States

John Vanderlyn, 1816

In the White House 1809-1817

In preparation for the inaugural ceremonies on March 4, 1809, the commandant of the Washington Navy Yard requested Dolley’s permission and sponsorship of a dance and dinner, and she readily agreed; thus, the first Inaugural Ball took place that evening. Held at Long’s Hotel on Capitol Hill, four hundred guests attended. Dressed in a buff-colored velvet gown, wearing pearls and large plumes in a turban, Dolley made a dramatic impression.

With more conscious effort than either of her two predecessors, and with an enthusiasm for public life that neither of them had, Dolley Madison forged the highly public role as a President’s wife, believing that the citizenry was her constituency as well as that of her husband’s. This would establish her as the standard against which all her successors would be held, well into the mid-20th century.

This persona was specifically created to serve the political fortunes of not only the President, but also of the United States. She would steer conversation with political figures in a way that revealed their positions on issues facing the Madison Administration, or sought to convince them to consider the viewpoint of her husband. She held dove parties where congressional wives discussed current events, hosted political dinners, and gave wildly popular public receptions.

She was also the first to decorate the White House. Working within a tight budget, Dolley balanced the elegance required to impress international visitors and the modesty of a republican nation. Through her purchases of wallpaper, furniture, and china, Dolley Madison combined sophistication with simplicity. She completed her decoration of the White House by 1810, throwing a gala to display her achievements to the American public.

In 1814, while the War of 1812 was raging, the British Army advanced on Washington, and the President left the city to be on the front lines with the troops. He ordered his wife to leave, but she refused to leave until she heard cannon fire.

On August 24, 1814, British soldiers set fire to the White House, and fuel was added to the fires to ensure they would continue burning into the next day; the smoke was reportedly visible as far away as Baltimore. Dolley commandeered a large wagon off the street and helped the servants load it with vital state documents, the President’s papers and books, her favorite silver and china, and at the last minute, Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington.

The fire in the White House destroyed the interior and charred much of the exterior. Reconstruction began almost immediately. Colonel John Tayloe III offered the use of his home, The Octagon House, to the Madisons as a temporary Executive Mansion, and they resided there for the remainder of his term. Madison used the circular room above the entrance as a study, and in that room in 1815, he signed the ratification papers for the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812.

At Montpelier 1817-1837

On April 6, 1817, Dolley and James Madison returned to their estate in Orange County, Virginia. In 1830, Dolley’s son by her first marriage, Payne Todd, a gambler and an alcoholic who never married nor had a career, went to debtors prison in Philadelphia. The Madisons sold land in Kentucky and mortgaged half of the Montpelier estate to pay Todd’s debts.

Madison used his retirement to organize his papers for publication, especially his notes from the Constitutional Convention. In this effort, Dolley was his helpmate, even serving as his hands when painful rheumatism kept him from writing. Madison always said he would not share these notes until the last of the delegates to the convention had died. As it turned out he himself was the last to pass away.

James Madison died at Montpelier on June 28, 1836, at the age of 85.

Thus the 41-year marriage between James and Dolley drew to a close. Theirs had been a supremely successful relationship on both a personal and a public level. Dolley remained at Montpelier for a year thereafter. One of her nieces, Anna Payne, daughter of her younger brother John Coles Payne came to live with Dolley, but she found life at Montpelier difficult.

In the fall of 1837, Dolley decided to leave Montpelier and again moved to Washington, DC, with her niece, leaving Payne Todd was to run the plantation. Dolley and Anna moved into a house Dolley’s sister Anna and her husband had bought. Dolley was socially in demand, and politically she was a living symbol of the generation of the Founding Fathers.

Dolley Madison had helped her husband organize and prepare his papers, including those he used in drafting the U.S. Constitution for public release. After his death, she continued to organize and copy her husband’s papers. It was left to Dolley to publish Madison’s papers, and they did not bring the money he had hoped would carry her through to the end of her life.

While Dolley was living in Washington, Payne Todd was unable to manage the plantation successfully due to alcoholism and resulting illnesses, leaving them without income. Dolley moved back to Montpelier to run the plantation, but failed to make a profit. Due to the increasing burden of vast debt accumulated by her irresponsible son, she was forced to sell their Virginia properties, including Montpelier.

In Washington 1844-1849

In 1844, Dolley Madison returned permanently to Washington, DC, and moved into another Madison property, a row house across the street from the White House. The former First Lady lived in near-poverty for several years, and was so poor that she had to accept hand-outs from friends. In 1847, she sold her slave Paul Jennings to her Lafayette Square neighbor, Daniel Webster.

Jennings later recalled:

In the last days of her life, before Congress purchased her husband’s papers, she was in a state of absolute poverty, and I think sometimes suffered for the necessaries of life. While I was a servant to Mr. Webster, he often sent me to her with a market-basket full of provisions, and told me whenever I saw anything in the house that I thought she was in need of, to take it to her. I often did this, and occasionally gave her small sums from my own pocket.

In 1844, the United States House of Representatives dedicated an honorary seat in Congress for Dolley, allowing her to watch congressional debates from the floor, where members sat at their desks. From the White House she was the first private citizen to transmit a message via telegraph, an honor given her by its inventor Samuel F. B. Morse.

In 1848, Congress finally purchased James Madison’s papers for the sum of $25,000. Of this sum, Dolley invested $20,000 in a trust fund out of fear that Payne Todd would waste it on gambling and alcohol. During this time, Dolley served as Honorary Chair of a women’s group to raise funds for the Washington Memorial. Her last public appearance was on the arm of President James K. Polk at his last White House reception.

Dolley Payne Todd Madison died at her home in Washington, DC, July 12, 1849, at the age of 81. Her funeral was a state occasion, attended by the president, the cabinet officers, the diplomatic corps, members of the House and Senate, the justices of the Supreme Court, officers of the army and navy, the mayor and city leaders, and “citizens and strangers.”

Sometimes referred to today as the first First Lady, the title actually came from her eulogy which was delivered by then-President Zachary Taylor, who referred to her as “the first lady of the land for half a century.” Her final legacy was to inspire the term by which the presidents’ wives have been known ever since.

Her remains originally went to the Congressional Cemetery, but were later transported to Montpelier and now rest next to her husband’s in the Madison Family Cemetery.

SOURCES

Dolley Madison

The Dolly Madison Project

Wikipedia: Dolley Madison

Wikipedia: James Madison

Montpelier.org: James Madison

Chronology of Dolley Payne Madison

First Lady Biography: Dolley Madison