Loyalist Woman of Westover Plantation in Virginia

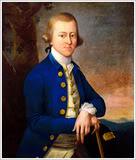

Mary Willing Byrd Portrait

John Wollaston, 1758

This portrait was painted in Philadelphia three years before she met and married the older William Byrd III (1728–1777).

Mary Willing was born on September 10, 1740, the daughter of Charles and Anne (Shippen) Willing. Her father was the mayor of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1748 to 1754, and her great-grandfather, Edward Shippen, was the second mayor of Philadelphia from 1701 to 1703. Benjamin Franklin was one of Mary’s godfathers, and when she was a child, he sent her books from Europe.

William Byrd III was born September 6, 1729, the son of Colonel William Byrd II and his second wife, Maria Taylor. He was raised at Westover, the family estate in Charles City County, Virginia. In 1744, Byrd went to London to study law at the Middle Temple. This is likely where he started gambling, a weakness that plagued him the rest of his life.

Byrd III returned to Virginia, and on April 14, 1748, married Elizabeth Hill Carter, the only daughter of John Carter of nearby Shirley Plantation. Not yet 21 when he married, Byrd gained full control of an estate that included more than 179,000 acres, hundreds of slaves, mills, fisheries, vessels, warehouses, and a store. Byrd also assumed all of the other roles an upper class Virginian was expected to fill.

Byrd could not live within his means, and as early as 1755 he was in dire financial straits. He conveyed his estate in 1756 to seven trustees, who sold land and slaves worth £40,000, a huge sum that still did not pay off his debts. In 1768, Byrd resorted to a lottery, the prizes for which were to come from his estate at the falls of the James River. Even these efforts did not cover his debts.

Byrd was an avid gambler. His favorite vice was high-stakes gambling on horse racing. He owned some of the most celebrated race horses of his day. He also won and lost large amounts at cards. As a result of his financial straits, he sold by lottery his lots in Richmond and Manchester. The vast estate built up by his father and grandfathers was nearly lost during his lifetime.

After turning his estate over to his trustees and sending his three eldest children to England in the care of an uncle and aunt, Byrd volunteered for service in the British forces in North America during the French and Indian War.

A report circulated that he had entered the military as a less than subtle way of abandoning his first wife Elizabeth, who was said to be even more immature and spoiled than he was. Byrd did not see his wife again. After writing him affectionate letters that begged him to return, Elizabeth Carter Byrd died on July 25, 1760, a probable suicide.

Byrd was in military service from 1756 until 1761. He served in Nova Scotia, the Carolinas, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. In 1758 he became colonel of the 2nd Virginia Regiment, and the following year he succeeded George Washington as commander of the 1st Virginia Regiment. After an abortive campaign against the Cherokee, Byrd resigned his command in September 1761. While in winter quarters in Philadelphia in 1760, Byrd met Mary Willing.

On January 29, 1761, William Byrd III married Mary Willing, within six months of his first wife’s death. Byrd had five children from his first marriage, and he and Mary had four sons and six daughters.

William and Mary lived in Philadelphia until 1762, when they moved to Charles City County, Virginia, to live at Westover, the Byrd family estate. There Mary found her English-born mother-in-law “a most sensible, cheerful woman, always gay and amiable.” With reference to the network of Virginia dynasties, Mary added, “She is the only person I dare open my heart to. They are all brothers, sisters, or cousins; so that if you use one person in the colony ill, you affront all; except the governor’s family, and my mother.”

The new bride received Byrd’s two youngest children by his first wife with the same warmth, and she was more than pleased as well with the Westover estate: “This is the most delightful place in the world.” But her husband’s retirement brought a return to extravagant spending. Mary’s rapport with her mother-in-law cooled. By 1769 Byrd was bankrupt.

Byrd took an active role in the management of his business affairs, and worked to pay off his debts and provide for his children. In addition to producing large amounts of tobacco, he offered 11,000 bushels of wheat for sale in 1770, and he also operated a lead mine in southwestern Virginia, and an iron forge near Richmond.

Byrd continued to enjoy a very expensive lifestyle and does not seem to have denied himself or his family in any way. His life was luxurious but not idle. He apparently worked hard, continued trying to increase his income, and sold some of his eastern land in order to acquire property farther west. He also remained active in public affairs and unsuccessfully sought appointment as secretary of the colony.

Byrd’s later life was not easy. He was unable to retire his debts; the lottery was largely a failure; two of his sons ran amok at the College of William and Mary, destroyed property, and threatened the institution’s president; and the death of his mother in 1771 left him owing £5,000 to his children by his first wife.

On July 6, 1774, a thoroughly unhappy Byrd made his will, disposing of an estate that “thro’ my own folly and inattention to accounts the carelessness of some intrusted with the management thereof and the vilany of others, is still greatly incumbered with Debts which imbitters every moment of my Life.”

In sixteen years of married life, Mary Willing Byrd gave birth to ten children:

Maria Horsmanden Byrd, Anne Willing, Charles Willing (died as child), Evelyn Taylor, Abby, Dorothy (died as child), a second son named Charles Willing Byrd (a common practice when the first child died), Jane, Richard Willing, and William IV, born soon after his father’s death.

William Byrd III had managed to bury himself deeply in debt from gambling and mismanagement, and he feared that his loyalty to the crown had put him on the wrong side of history. On New Year’s Day 1777, he put a pistol to his head and killed himself at Westover, at the age 48. His will directed that he be buried in the old Westover Church Cemetery.

His financial difficulties fell upon Mary’s shoulders. She was left to raise her children and run a large plantation on her own, and to face the difficult task of satisfying his creditors while preserving an inheritance for her ten children. For the next thirty-seven years she proved equal to the task.

Westover Mansion

Charles City County, Virginia

A mansion in the Georgian style, the house is noteworthy for its secret passages, magnificent gardens, and architectural details. Like the other plantations along the James River, Westover was first devoted to the cultivation of tobacco, the major commodity of colonial Tidewater Virginia. The Byrd family depended on the labor of hundreds of enslaved Africans, as tobacco was a labor-intensive crop.

Using her shrewd economic judgment, Mary Byrd kept possession of Westover by selling off many of her husband’s remaining assets, including a large number of slaves, western lands, residences in Richmond and Williamsburg, and his father’s extensive and well-known library.

In late 1780, General George Washington warned the governor of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson, of imminent invasion, but Jefferson doubted initial reports that British ships were sailing into the Chesapeake Bay.

Before dawn on January 4, 1781, Thomas Jefferson was startled by the news that a large fleet of British warships was nearby on the James River. He realized they planned to take Richmond and capture him. After sending off his wife and three daughters, he mounted his horse and rode through the city, issuing orders to raise the militia and remove important state papers. Then he galloped safely away.

Led by that famous traitor Benedict Arnold, the British fleet docked at and occupied Westover. A thousand acres of fields, forest and swamp, Westover was being held together by Mary Willing Byrd, whose patriotism was in some doubt. But what raised eyebrows the most was the fact that her first cousin Peggy Shippen was Arnold’s wife.

During the American Revolution, Mary tried to remain neutral. In his book, Flight from Monticello, Thomas Jefferson at War, Michael Kranish writes, “She harbored resentment against revolutionaries, whom she blamed for her husband’s suicide, and yet was also a subject of sympathy because of the vast obligations she was left on the day Byrd died.”

Hundreds of British soldiers set up tents on the grounds of the Westover estate, helped themselves to crops, slaughtered animals and made off with dozens of her slaves – although Arnold promised she would be compensated. But they left her house and its contents undisturbed, then marched off and invaded Richmond.

Mary received her sudden guests with “propriety,” as she later wrote to Jefferson. “I consulted my heart and my head, and acted to the best of my judgment, agreeable to all laws, human and divine. If I have acted erroneously, it was an error in judgment and not of the Heart.”

When the British left Westover, they took with them slaves, horses, and two ferryboats. Under an American flag of truce, Mary Byrd tried to recover some of her property. This action embroiled her in controversy and led to formal charges that she was trading with the enemy. On February 21, 1781, a company of American infantry raided Westover, seizing her papers.

Two days later Mary wrote a letter to Governor Jefferson, defending her loyalty: “I wish well to all mankind, to America in particular. What am I but an American? All my friends and connexions are in America; my whole property is here – could I wish ill to everything I have an interest in?”

Although he was sympathetic, Thomas Jefferson later joined with members of his council in passing a resolution accusing her of treason. She protested that she had done nothing wrong. “I would rather die than betray my country,” she wrote a friend.

But Mary would have to defend herself in court and face the consequences – loss of property, jail or even execution. She went by carriage to Richmond to face her accusers, but was informed when she arrived that a key witness was unavailable and the case was dropped. No explanation was ever given, but it appeared that well-connected Virginians had deliberately detained the witness.

In August 1781, Mary asked the governor for another flag of truce in order to continue her efforts to recover her property. During the final British withdrawal from the United States in 1783, she appealed to the British commander to honor previous promises of restitution.

Mary Byrd’s determination successfully preserved much of her property and the legacy of one of the great families of colonial Virginia. When she prepared her will in December 1813, she was still in possession of Westover and could provide for all of her children and grandchildren. Not until after her death was Westover sold outside of the Byrd family.

Part of her will reads:

“In the name of God Amen, I Mary Byrd of Westover of the County of Charles City, Virginia, being of sound mind and memory do make this my last will and testament. I resign my soul into the hands of its unerring Creator in full hope of its eternal happiness through the mercy of my god and the mediation of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, and secondly I desire that my body may be privately buried by the grave of my dear husband.”

Mary Willing Byrd died at the Westover estate in March 1814. She was buried next to William Byrd III in the old Westover Church Cemetery, one-quarter mile from the mansion.

Her son Charles Willing Byrd (July 26, 1770 – August 25, 1828) was an early Ohio political leader and a Federal judge.

SOURCES

William Byrd III

Virginia Memory

American Memory

Our Stories by Paul Clancy

VaHistorical.org: Virginia’s Colonial Dynasties

Wikipedia: Mary Willing Byrd

Mary Willing Byrd, Charles City County Planter