Wife of Declaration Signer Richard Henry Lee

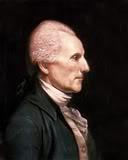

Richard Henry Lee

Charles Willson Peale, Artist

National Portrait Gallery

Smithsonian Institution

Richard Henry Lee was born on January 20, 1733, at his family’s plantation, Stratford Hall, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, the seventh of eleven children. Perhaps the most wealthy and powerful individual in Virginia, his father, Thomas Lee, was president of the Virginia Council of State and the principal founder of the Ohio Company. The Lees were a Revolutionary dynasty that included not only Richard Henry, but his brothers Arthur, William, and Francis Lightfoot Lee.

Richard was educated early on in life by private tutoring at home. In 1748, his father sent him to England to be educated. There he attended Wakefield Academy in Yorkshire, where he became fluent in Latin and Greek. His formal education ended at age twenty, followed by a lengthy tour of northern Europe, and he returned to Virginia in 1753. Back at Stratford Hall, he supplemented his education by studying law, government, history, and the classics.

On December 5, 1757, Richard Henry Lee married Anne Aylette, and they had four children: Thomas, Ludwell, Mary, and Hannah. The family lived at Stratford Hall until 1763, when they moved to Chantilly-on-the-Potomac, a three-and-a-half story, ten-room home he had built on a bluff overlooking the Potomac River. Situated on 500 acres three miles away from Stratford Hall, Chantilly was said to have a finer view of the Potomac River.

At Chantilly, Lee became a gentleman farmer, growing tobacco, corn, and wheat and raising livestock. Chantilly’s outbuildings included a kitchen, a barn, a dairy, a blacksmith shop, and various stables. A boat dock constructed at nearby creeks was christened Chantilly Landing.

Political Career

Richard Henry Lee’s political career began in 1755, when he was appointed a justice of the peace in Westmoreland County. In 1758, he was elected to the . Lee often served on important committees, some of which thrust him into the center of political controversy. In 1757, Lee joined forces with Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie in opposing the powerful speaker and treasurer of Virginia, John Robinson, who was using colonial funds to the advantage of his political cronies. Lee introduced the motion in the House of Burgesses to appoint a committee to inquire into the state of the treasury, leading to the separation of the two offices.

As a member of Virginia’s House of Burgesses, Richard Henry’s first bill proposed “to lay so heavy a duty on the importation of slaves as to put an end to that iniquitous and disgraceful traffic within the colony of Virginia.” Africans, he wrote, were “equally entitled to liberty and freedom by the great law of nature.” Such words, coming as they did in 1759, have been called “the most extreme anti-slavery statements made before the nineteenth century.” This speech helped establish his reputation as a great orator, second only to Patrick Henry.

In 1765, enforcement of the Stamp Act began. Richard Henry co-authored the Westmoreland Resolves, binding citizens to support “our lawful sovereign, George the Third… so far as is consistent with the preservation of our rights and liberty.” The public signing of the Westmoreland Resolves by prominent landowners, including Richard Henry, Thomas, Francis Lightfoot, and William Lee and the four brothers of George Washington, was one of the first deliberate acts of resistance against British rule.

In 1767, the Townshend Acts renewed Lee’s militancy. He strongly supported the boycott of British goods and wove cloth on his own looms and pressed his own grapes for wine. He introduced a motion in the House of Burgesses calling for a petition to the king outlining the colonies’ grievances.

In 1768, Richard Henry proposed the systematic interchange of information among “lovers of liberty in every province.” As a result, the Committees of Correspondence were formed and became a major force uniting the Americans in their desire for independence. Receiving first-hand information on the decisions of the King and Parliament from his brothers, Arthur and William, now in London, he served as a communications commander for the colonies.

During the winter, Lee went goose hunting, one of his favorite sports. His gun exploded in his left hand, and he lost all four fingers. The wound was cauterized with a white-hot iron, and it healed over a period of months. Thereafter, he wore a black silk cloth glove to hide his scarred hand, which he used to great effect when giving public speeches.

Anne Aylett Lee died of pluerisy on December 12, 1768, at the age of thirty, leaving four young children.

In July 1769, Richard Henry Lee married widow Anne Gaskins Pinckard, a descendant of three Mayflower Pilgrims, who had two children from her first marriage. They had five more children: Anne, Henrietta (Harriotte), Sarah Caldwell (Sally), Cassius, and Francis Lightfoot.

The House of Burgesses protested the Townshend Acts in 1769, and Royal Governor Botetourt dissolved that governing body for its disrespect. At the suggestion of Richard Henry Lee, the bolder members met in a private room at the Raleigh Tavern. There they formed a nonimportation association, agreeing to suspend the purchase of goods from British merchants.

Lee initially favored a policy of economic boycott to bring the British to reason in their colonial policies, but he began to change his mind when the King closed the Port of Boston on March 7, 1774, after the Boston Tea Party.

On May 27, 1774, Royal Governor Dunmore dissolved the House of Burgesses again for objecting to the closing of the Port of Boston, and 89 burgesses met again at the Raleigh Tavern to form another non-importation association. George Mason drafted the association agreement, and George Washington introduced it.

By 1774, the flames of the Revolution had ignited the reluctant southern colonies. The call for an inter-colonial congress was made, and Richard Henry Lee was chosen as one of the seven-man Virginia delegation to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia – along with Patrick Henry and George Washington. On September 5, 1774, the delegates met at Carpenters Hall for the first meeting of the Congress.

Lee’s speeches were often powerful, academic and sometimes spontaneous. “The great orators here,” wrote John Adams, “are Lee, Hooper and Patrick Henry.” St. George Tucker of Virginia described Lee’s speeches: “The fine powers of language united with that harmonious voice, made me sometimes think that I was listening to some being inspired with more than mortal powers of embellishment.”

Lee and Adams became a powerful team, often meeting with Adams’ cousin, Samuel Adams, at Lee’s sister’s house in Philadelphia. Sister Alice had married physician William Shippen, Jr., who would become the chief medical officer in the Revolution. There, Lee strengthened his bond with John and Samuel Adams, and created a long-lasting friendship that bridged the gap between the vastly different worlds of New England and the South, and helped to unite the colonies as one nation.

The Road to Independence

The original thirteen British colonies of mainland North America moved toward independence slowly and reluctantly. The colonists were proud of being British and had no desire to be separated from their mother country. Not even the outbreak of war at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, in April 1775 produced calls for independence.

In July 1775, the Second Continental Congress sent the King a petition for redress and reconciliation, which was drafted in respectful language. The king did not formally answer the petition. Instead, in a proclamation of August 23, 1775, he asserted that the colonists were engaged in an “open and avowed rebellion.”

Then, on October 26, he told Parliament that the American rebellion was “manifestly carried on for the purpose of establishing an independent Empire,” and that the colonists’ professions of loyalty to him and the “parent State” were “meant only to amuse.”

News of the king’s speech arrived at Philadelphia in January 1776, just when Thomas Paine’s Common Sense appeared. American freedom would never be secure under British rule, Paine argued, because the British government included two grave “constitutional errors,” monarchy and hereditary rule.

In May 1776, Congress passed a resolution written by John Adams that called for the total suppression of “every kind of authority under the … crown” and the establishment of new state governments “under the authority of the people.” Simultaneously, on May 15, Virginia instructed its Congressional delegation to move that Congress declare independence, negotiate foreign alliances, and design an American confederation.

On June 7, 1776, acting under the authorization and approval of the Virginia Convention, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution to the Second Continental Congress, proposing Independence for the thirteen colonies, which contained three parts: a Declaration of Independence, a call to form foreign alliances, and a plan of confederation. John Adams seconded the motion.

The Lee Resolution:

(1) Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

(2) That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.

(3) That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.

After introducing his resolution, Lee made one of the most eloquent speeches ever delivered on the floor of Congress:

Why then, sir, why do we longer delay? Why still deliberate? Let this happy day give birth to an American Republic. Let her arise, not to devastate and to conquer, but to reestablish the reign of peace and of law. The eyes of Europe are fixed upon us: she demands of us a living example of freedom, that may exhibit a contrast in the felicity of the citizen to the ever increasing tyranny which desolates her polluted shores. She invites us to prepare an asylum, where the unhappy may find solace, and the persecuted repose.

Congress debated Lee’s resolution on June 8, and again the following Monday. On June 11, 1776, the Congress appointed three committees in response to the Lee Resolution: one to draft a Declaration of Independence, a second to draw up a plan “for forming foreign alliances,” and a third to “prepare and digest the form of a confederation.” Lee was appointed to the committee responsible for drafting a declaration, but he was called home when his wife fell ill, and his place was taken by his young protege, Thomas Jefferson.

Because many members of the Congress believed action such as Lee proposed to be premature or wanted instructions from their colonies before voting. Final approval for the first part, a Declaration of Independence, was deferred until July 2. According to notes kept by Thomas Jefferson, most delegates conceded that independence was justified, but some argued for delay. The colonies should negotiate agreements with potential European allies before declaring independence, they said.

On June 28, 1776, the committee submitted its draft to Congress. Meanwhile, towns, counties, grand juries, and some private groups publicly declared their support for independence. On July 1, when Congress again debated independence, sentiment remained divided, with nine states in favor, two (Pennsylvania and South Carolina) opposed, and one (Delaware) split. New York’s delegates abstained because their year-old instructions from their state had not been changed.

On July 2, Congress adopted the first part of the Lee Resolution – the first official act of the United Colonies that set them on the road to Independence – with twelve in favor, none opposed, and New York still abstaining. The second part, the plan for making treaties, was not approved until September of 1776; and the third part, the plan of confederation, was delayed until November of 1777.

The delegates then spent most of the next two days editing the document. Finally, on July 4, Congress approved the revised text of the Declaration of Independence, prepared principally by Thomas Jefferson, then ordered that it be printed and authenticated under the supervision of the drafting committee and distributed to the states and Continental Army commanders so it could be “proclaimed in each of the United States, and at the head of the army.”

![]()

Richard Henry Lee Signature

On the Declaration of Independence

On July 9, New York added its consent to that of the other twelve states. And on July 19, Congress resolved “that the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and style of ‘The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,'” and that the parchment copy should be signed “by every member of Congress.”

The main signing occurred on August 2, 1776. Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee were the only brothers to sign the Declaration of Independence. However, it was not until January 1777—after the American victories at Trenton and Princeton, New Jersey, had ended the long disastrous military campaign of 1776—that Congress sent authenticated copies of the signed Declaration to the states.

At that same time, Lee was working with George Wythe drafting a new state constitution for Virginia. Immediately after signing the Declaration of Independence, Lee departed for Virginia to lobby for their plan, and the Virginia Convention ultimately ratified a similar proposal. Lee also wrote the first national Thanksgiving Day proclamation, issued on October 31, 1777.

Lee had enemies who spoke against him in Virginia and in the Congress. False rumors spread that Lee and others were attempting to depose his friend George Washington, and Lee was accused of misuse of his public office for personal gain. Defeated in 1777, when Virginians chose the next Continental Congress delegates, Lee requested a formal investigation by the Assembly.

George Wythe, then Speaker, explained the results during the Assembly. “You manifested in the American cause a zeal truly patriotic… That the tribute of praise deserved may reward those who do well and encourage others to follow your example, the House have come to this resolution: ‘Resolved, That the thanks of this House be given by the Speaker, to Richard Henry Lee, Esq., for the faithful service he has rendered to his country, in discharge of his duty, as one of the delegates from this State in general Congress.'”

Stratford Hall

Birthplace of Richard Henry Lee

Most of Lee’s early work in the House of Delegates had revolved around supplying the Virginia militia, and in 1779 and 1781, he took an active part in organizing the defense of the Potomac River against British attacks. During the spring of 1781, the British burned houses and tobacco warehouses along the Potomac River. Richard Henry was re-commissioned as colonel in the Westmoreland militia, moving his family away from Chantilly as disaster was expected.

Observing three British ships approaching the Stratford wharf, he called up the militia. As the British embarked, the Americans fired. At least one British soldier was killed and others were wounded as the British retreated. “I am at present lamed by my horse falling on me in a late engagement with the enemy who landed under cover of heavy cannonades from three vessels of war upon a small body of our militia were posted,” wrote Lee to his friend Samuel Adams April 1. “After a small engagement we had the pleasure to see the enemy, tho superior in numbers, run to their boats and precipitately reembark having sustained a small loss of killed and wounded.”

After the Revolutionary War, Lee returned to Congress, and served as President of Congress, from 1784 to 1785, under the Articles of Confederation. He was an anti-federalist who tended to support the proposed Constitution, provided it could be amended before being voted upon. To that end, he proposed amendments and supported the Bill of Rights, but he did not attend the Constitutional Convention.

Lee did accept, however, the office of U.S. Senator under the new government, and in fact gained more votes than any other contender. In the Senate, he guarded the anti-federalist positions, but was known as a moderate with whom one could compromise. He served as a Senator from Virginia from 1789 to 1792.

However, his health declined after his right hand was so affected he required a personal secretary. Then his carriage overturned in the fall of 1791, and he was severely injured. He did not resume his seat until December 1791, and ended his work there when Congress adjourned May 7, 1792. He then retired to his estate, Chantilly. During the last two years of his life, he was greatly enfeebled, and for the last six months of his life, he mostly was confined to his home.

Richard Henry Lee died at Chantilly on June 19, 1794, at the age of 61. He was buried at the family cemetery along with his parents and grandparents, and between his two wives, at Burnt House Field, the Lee Family estate about twenty miles away that burned to the ground in 1729.

During Richard Henry Lee’s political career, he was an energetic and important member of every body that he served in, and his oratory skills earned him the title of Cicero of the American Revolution. John Adams described him as a “tall spare man … a scholar, a gentleman, a man of uncommon eloquence.”

Richard Henry Lee is a key character in the musical 1776. He was portrayed by Ron Holgate in both the Broadway cast and in the 1972 film. The character performs a song called The Lees of Old Virginia, in which he explains how he knows he will be able to convince the Virginia House of Burgesses to allow him to propose independence.

Richard Henry Lee has been the subject of several books:

James Ballagh’s The Letters of Richard Henry Lee

His autobiography, Memoir of the Life of Richard Henry Lee

Oliver Chitwood’s Richard Henry Lee: Statesman of the Revolution

J. Kent McGaughy’s Richard Henry Lee of Virginia: A Portrait of an American Revolutionary

Cazenove Gardner Lee, Jr.’s Studies of the Early Generations of the Lees of Virginia

SOURCES

Richard Henry Lee

Lee Resolution (1776)

Lee Family Digital Archive

Richard Henry Lee: Virginia

Richard Henry Lee 1732-1794

Declaration of Independence

Wikipedia: Richard Henry Lee

The Architect of Independence

A Biography of Richard Henry Lee

6th President of the United States in Congress Assembled