Wife of Signer of the Declaration and the Constitution George Clymer

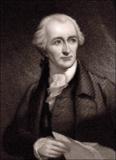

George Clymer

Elizabeth Meredith was born in 1743, the daughter of Reese Meredith, a prominent and wealthy merchant in Philadelphia for more than half a century prior to the Revolutionary period. She was described as a handsome accomplished girl of most exemplary character. Reese Meredith and George Washington were friends, long before the Revolution. According to legend, Mr. Meredith was lunching at an inn in Philadelphia, and started a conversation with a tall young Virginian, and before separating, Mr. Meredith invited the young man to his home, and Washington accepted, and the friendship continued for the rest of their lives.

George Clymer was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on March 16, 1739. His mother, Deborah Fitzwater Clymer, died when he was a year old; his father, Christopher Clymer, a sea captain, died when he was seven. George was raised by his maternal aunt and uncle, Hannah (his mother’s sister) and William Coleman, a friend of Benjamin Franklin, who said Coleman had “the coolest, clearest head, the best heart, and the exactest morals of almost any man I ever met with.”

Clymer’s uncle, William Coleman was a wealthy merchant and judge who kept a large private library, and young George learned to love reading while growing up. George received a liberal education at the College of Philadelphia, and two years’ training in his uncle’s accounting house. George became a clerk and a partner in his uncle’s mercantile firm in the late 1750s.

In March 1765, he married Elizabeth Meredith. It was considered a highly advantageous union on both sides. Their married life was very happy, and was only marred by the forced separations and hardships caused by the Revolution. Eight children were born to Elizabeth and George Clymer, and five children survived to adulthood: Henry, Meredith, Margaret, Nancy, and George. Elizabeth and their children had to move several times during the Revolutionary War to avoid capture by the British.

Clymer came into a substantial inheritance after his uncle died in 1769. Sometime thereafter, Clymer formed a partnership with his inlaws to form Meredith-Clymer, a leading Pennsylvania merchant house. Elizabeth’s socially prominent family also introduced Clymer to George Washington and other Patriot leaders. His father-in-law was host to Washington on his visits to Philadelphia; Washington and Clymer formed a lasting friendship.

Clymer was a successful businessman, but in this new country his entire sympathy was with the rights of the people. Motivated at least partly by the impact of British economic restrictions on his own business, Clymer early adopted the Revolutionary cause. He was opposed to England’s tax plan, and went to Boston to gain firsthand knowledge, returning to Philadelphia filled with an intense desire for complete independence from England.

An active Patriot, Clymer headed the committee to persuade Philadelphia merchants not to sell British tea sent over in 1773, leading to a boycott. In 1773, he led a committee of Pennsylvania Patriots that forced the resignation of the Philadelphia tea consignees appointed by Parliament under the Tea Act, and became a member of the Committee of Safety.

By 1774, Clymer had the second highest residential tax assessment in Philadelphia and ranked third in gross income from property. A modest man and cool on the surface, Clymer never sought political office, but for twenty years, he was in almost constant public service.

Within days of the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, Clymer was elected Captain of a volunteer battalion called the Pennsylvania Silk Stockings, because of their fancy uniforms. Although his unit did not actually fight in the war, Clymer supplied the Continental Army with gunpowder, flour, corn, and tents from his merchant business.

He made a significant contribution to the cause of liberty by organizing essential congressional support for military reforms and by personally helping to reorganize the Continental Army. As a politician, he tended to avoid the limelight, preferring to work on committees where he could bring his administrative skills to bear. He was a soft-spoken man who, as a contemporary said, “was never heard to speak ill of anyone.”

Clymer served as Continental treasurer (1775-76), an office organized by the Continental Congress to supervise the financing of the Revolution. He proved his faith in the new government by exchanging his own money (gold, silver, and British pounds) for the paper currency issued by the Continental Congress, which later became worthless. He also supported the Continental Loan, a plan advanced by Congress to finance the Revolution with money borrowed from the citizenry.

![]()

Signature on the Declaration of Independence

In 1776, Clymer was one of the delegates elected to the Continental Congress because of his pro-independence views, and from that time practically gave up his private business, and devoted himself to public affairs. In Congress, he was an untiring worker, whose cool judgment and unswerving patriotism were recognized by everyone. While no orator, he was well informed, a witty conversationalist, and a good writer. At the time, Clymer was a prosperous merchant who was praised as one of the wisest of all delegates. His “dearest wish” came to life when he signed the Declaration of Independence.

Clymer was the first treasurer of the central government and worked with Robert Morris in planning the financial affairs of the united colonies, which was then a treasury without funds. The problems Morris and Clymer faced were almost insurmountable, problems that would have been (and were thought) hopeless by all but these two. Clymer was sent to inspect the northern army on behalf of Congress in the fall of 1776.

His work in helping to organize the resupply of Washington’s battered main army during those crucial months made the victories at Trenton and Princeton possible. Clymer subsequently became deeply involved in Continental Army affairs, even visiting units in the field. He worked hard to improve the lot of the common soldier, supporting Washington’s efforts to improve administrative efficiency, especially by reforming the Army’s commissary system.

On September 26, 1777, the British army marched into Philadelphia. When the Congress fled to Baltimore to escape capture by the advancing British, Clymer, George Walton, and Robert Morris remained behind to carry on congressional business during the winter of 1776-77. Clymer also worked with Elbridge Gerry, another of the signers of the Declaration, in his efforts for financial reform.

Elizabeth Clymer and her children fled for safety to their country home in Chester County, 25 miles outside the city, but some local Tories led the enemy to their retreat. The house was vandalized and the furniture destroyed; the wine cellars were raided, and everything portable on the place was carried away, while the family hid nearby in the woods.

Clymer was elected a trustee of the Academy and College of Philadelphia in 1779, serving in that capacity until 1791, including a stint in 1779 and 1780 as the board’s treasurer. When the College was combined with the University of the State of Pennsylvania in 1791, he was elected trustee of the resulting University of Pennsylvania, and served in that position until his death. In 1797, when it looked as if the school would have to close, he and the other trustees took out personal loans to keep it going.

After being out of Congress for several years, Clymer again served as a Pennsylvania delegate from 1780 to 1783. In 1780, Clymer was elected to a seat in the Pennsylvania Legislature. In 1782, he was sent on a tour of the southern states in a vain attempt to get the legislatures to pay up on subscriptions due to the central government.

After the Revolution, Clymer represented his state at the Federal Constitutional Convention in 1787. There, Clymer served on the committees concerned with the military, commercial, and financial powers and responsibilities of the new government. An advocate of a strong central government, he supported the Federalist position taken by Washington, Hamilton, and Madison. He became one of only six men who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution.

In 1789, Clymer was elected to the first United States Congress under the Constitution he had helped to create, where he remained loyal to his friend Washington, but tended to side with Madison against Hamilton.

In 1791, the government decided to tax every barrel of whiskey distilled in the United States in order to pay off the national debt. After serving one term in Congress, Clymer was appointed to the disagreeable task of collecting those taxes during what became known as the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania, when the farmer-distillers of that region defied the Federal Statute fixing a tax on whiskey. The insurrection was subdued with the help of some fifteen hundred soldiers, one of whom was the Clymers’ son Meridith. Clymer found the office distasteful and resigned after his son died at Fort Pitt in 1794.

Clymer was also a member of the commission that negotiated a treaty with the Cherokee and Creek Indians at Coleraine, Georgia, on June 29, 1796. It was his last public service.

The Signer, sculpted by Evangelos Frudakis in 1980, was dedicated in Signers Park on the former site of the Gilbert Stuart House in 1982 during Philadelphia’s Tercentenary. Inspired by George Clymer, a Philadelphia merchant, statesman and signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution, the monument “commemorates the spirit and deeds of all who devoted their lives to the cause of American Freedom.” The Signer is looking heavenward, holding a founding document within his grasp. The bronze statue, standing 9-1/2 feet high on a 6-foot granite base, was a gift of the Independence Hall Association.

In his retirement, Clymer became a philanthropist, and devoted himself to fine arts and scientific agriculture. He was the first president of the Philadelphia Bank and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and vice-president of the Philadelphia Agricultural Society.

On September 7, 1805, George and Elizabeth Clymer appeared before a justice of the court in Philadelphia and gave a deed for 250 acres of land to the trustees of Indiana County for a token payment of five shillings. Two of the Clymer’s children, Ann and George, Jr., witnessed the transaction.

In 1806, the Clymers purchased and moved into Summerseat, an estate a few miles outside Philadelphia at Morrisville, New Jersey. Summerseat was built in the 1770s for Thomas Barclay, a Philadelphia merchant. The two-story brick and stone Georgian structure built over an elevated basement, has a gabled and slate-covered roof. The house is fifty-two feet wide and thirty-six feet deep.

George Clymer died at Summerseat on January 23, 1813, at the age of 73. He was buried in the Friends Meeting House Cemetery at Trenton, New Jersey.

Elizabeth Meredith Clymer died in 1815.

SOURCES

George C. Clymer

George Clymer Memorial

George Clymer 1739-1813

Elizabeth Meredith Clymer

Wikipedia: George Clymer

America’s Founding Fathers

George Clymer: Pennsylvania

Signer of the Declaration of Independence