| George Wythe |

Wife of Signer George Wythe

George Wythe (pronounced “with”) was born in 1726 on his family’s plantation on the Back River in Elizabeth City County, Virginia. George’s father died when George was three years old, but fortunately, his grandfather had given his mother an excellent education, and George received his early education from her. She instilled in her son a love of learning that served him all his life.

In his teens, Wythe entered the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg. He was poor, however, and his stay was necessarily brief. A family connection opened the door for him to study in the law office of Thomas Dewey, and at age twenty he was admitted to the bar.

Admitted to the Virginia bar in 1746, moved to Spotsylvania County, and worked with the prominent lawyer Zachary Lewis. In 1747, Wythe married Zachary’s daughter Ann. Wythe was admitted to the York County bar January 16, 1748. Ann Lewis Wythe died on August 8 the same year.

In 1755, George Wythe married Elizabeth Taliaferro (pronounced “Tolliver”). She was the daughter of respected planter and builder Richard Taliaferro, who built a dignified house on the Palace Green in Williamsburg – now called the George Wythe House. Taliaferro gave his daughter and her new husband life rights to the house, and they lived there for many years. Their only child died in infancy.

At Williamsburg, Wythe immersed himself in further study of the classics and the law and achieved accreditation by the colonial supreme court. In 1755, George’s brother died and he inherited the family plantation, but George continued to live at Williamsburg, where he had been elected to represent the town in the House of Burgesses the previous year. He served in the House of Burgesses from the mid-1750s until 1775, first as delegate and after 1769 as clerk.

In 1759, when Thomas Jefferson was a 16-year-old freshman at the College of William and Mary, he met George Wythe, then 35, a lawyer and member of the House of Burgesses representing the college. Jefferson’s father had died two years earlier, and Wythe and his wife, Elizabeth, who had no children of their own, took Jefferson in.

Wythe first exhibited revolutionary leanings in 1764, when Parliament hinted to the colonies that it might impose a stamp tax. By then an experienced legislator, he drafted for the House of Burgesses a formal statement to Parliament so harsh that his fellow delegates modified it. Wythe was one of the first to express the concept of a separation of the colonies from the British empire. Yet, despite Virginia’s deepening disputes with the Crown, Wythe maintained close friendships with governors Francis Fauquier and Norborne Berkeley, baron de Botetourt.

Wythe was appointed to William and Mary’s board in 1768, and was elected Williamsburg’s mayor on December 1 of that year. He was appointed clerk of the House of Burgesses July 16, 1767, and took the oath of office on March 31, 1768. He remained house clerk until 1775, when he was elected to the Second Continental Congress.

Wythe continued to accept law students as boarders in his home, and treated them like the sons he never had. In 1772, he took James Madison (cousin of later President James Madison) into his home. Another student was Bermuda-born St. George Tucker, who later became United States judge for the District of Virginia. Among Wythe’s other law pupils were John Marshall, perhaps the greatest chief justice of the United States.

But Wythe’s greatest pupil was Thomas Jefferson. The two men together read all sorts of material other than law; from English literary works, to political philosophy, to the ancient classics. Wythe also instilled in Jefferson a love for books. An avid collector, Wythe accumulated an excellent library. In later years, a friendly rivalry developed between Wythe and Jefferson, as each sought to develop the best private library in Virginia.

As the War for Independence drew near, the controversies with Great Britain helped to crystallize Wythe’s thoughts on liberty. Wythe’s emphasis on the importance of liberty under the law helped to check Jefferson’s fiery spirit. Wythe argued that due to the slowness of communications with England, the American legislatures should be allowed to make laws to meet local needs. The growth in power of the colonial assemblies was part of the whole process of the mid-1700s, which saw the lower houses grow in power, confidence, and ability to govern.

Wythe’s mature political philosophy was similar to that of John Adams and James Madison. Wythe believed in the necessity of a “mixed government,” in which several “factions” checked each other’s power and influence. Ultimately, this concept found its practical expression in the three branches of government and in the relationship between the states and the national government. In 1776, at Wythe’s prompting, John Adams wrote his Thoughts on Government, in which he put forth the concept of separation of powers.

When the war began, though 50 years old, Wythe volunteered for Virginia’s army, but was instead called to serve in the Continental Congress. In Philadelphia, Wythe emphasized that “we must declare ourselves a free people.” Following instructions from the Virginia Convention in Williamsburg, Richard Henry Lee, another member of the Virginia delegation, rose at the Second Continental Congress and moved for American independence.

Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence was approved July 4, but the document was not ready for signing until August 2, 1862. By that time, Wythe had been called back to Virginia to help set up the new Commonwealth. Yet, George Wythe’s signature appears first among the Virginia signatories on the Declaration. He was so highly respected by his fellow Virginians that the other delegates left a space above their names so that Wythe could sign it when he returned.

![]()

George Wythe’s Signature

On the Declaration of Independence

In 1777, George Wythe returned to Virginia to revise the colonial laws and adapt them to her new status as a sovereign state. Unlike the revolutionaries in France and Russia, Wythe sought to build American laws on English precedents, confirming Edmund Burke’s observation that “the Americans are not only devoted to liberty, but to liberty according to English principles and ideas.” Wythe clearly saw the danger of disinheriting America from the Magna Charta, the English Bill of Rights, and England’s unique contribution to the progress of liberty.

George Wythe’s real love was teaching. In 1779, he accepted the appointment as professor of law and police in now-Governor Jefferson’s reorganization of the College of William and Mary. Wythe thus became the first professor of law in an American institution of higher learning. He held this position until 1790. In that position, he educated America’s earliest college-trained lawyers.

George Wythe House

Elizabeth Taliaferro’s father gave his daughter and her new husband life rights to this house on Palace Green in Williamsburg, Virginia, and they lived there for many years. It also served as General George Washington’s headquarters just before the Siege of Yorktown.

Wythe’s chief aim as an educator was to train his students for leadership. In a letter to his friend John Adams in 1785, Wythe wrote that his purpose was to “form such characters as may be fit to succeed those which have been ornamental and useful in the national councils of America.” Mr. Wythe’s School – both in his study and in the Wren Building at the College of William and Mary – produced a generation of lawyers, judges, ministers, teachers, and statesmen who helped fill the need for leadership in the young nation.

Late in the 1780s, student William Munford preserved a glimpse of Wythe’s domestic establishment. “Old as he is,” Munford wrote, “his habit is, every morning, winter and summer, to rise before the sun, go to the well in the yard, draw several buckets of water, and fill the reservoir for his shower bath, and then, drawing the cord, let the water fall over him in a glorious shower. Many a time have I heard him catching his breath and almost shouting with the shock. When he entered the breakfast room his face would be in a glow, and all his nerves were fully braced.”

During the Revolution, Wythe’s wealth suffered greatly. His devotion to public service left him little opportunity to attend to his private affairs. Due to the dishonesty of his superintendent, most of his slaves were placed in the hands of the British. But by cost-cutting and careful management, Wythe was able to pay off his debts and preserve his financial independence by combining what was left of his estate with his salary as chancellor.

In 1787, Wythe was chosen to be part of the Virginia delegation to the Constitutional Convention, joining what Jefferson called an “assembly of demigods.” George Washington appointed Wythe along with Alexander Hamilton and Charles Pinckney to draw up rules and procedures for the Convention. Delegates from the American States met in Philadelphia and began framing the Constitution of the United States. George Wythe was among those illustrious patriots – yet he was in the convention for only ten days.

He was called home by what he said was “the only” cause that “could have moved” him, the illness of his beloved wife. Elizabeth fell sick early in the summer, and on June 4, Wythe left the convention and headed back to Williamsburg.

Despite his best efforts, Elizabeth Taliaferro Wythe died on August 14, 1787, “after a long and lingering sickness which she bore with the patience of a true Christian.” She was 47 years old, and had been his wife for more than 30 years.

His wife gone, and having no children, Wythe once again answered the call of duty and fought for the passage of the Federal Constitution at the Virginia State Convention. Wythe’s prestige and influence, as well as the votes of five of his former students, helped to overcome strong opposition from the Antifederalists, led by Patrick Henry. Later, Wythe helped to develop the Bill of Rights, basing his work on George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights.

In a dispute with the administration, Wythe resigned from the college in 1789, and accepted an appointment as judge of Virginia’s Court of Chancery. In 1791, his chancery duties caused him to move to Richmond, the state capital, and he turned his home in Williamsburg over to the Taliaferro heirs. Wythe was reluctant to give up his teaching, however, and opened a private law school in Richmond. One of his last and most promising pupils was the future U.S. senator from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Wythe resigned as chancellor in 1792.

Wythe had grown to hate slavery, and after his wife died in 1787, he began to free his slaves and to provide for their support. In Richmond, Wythe lived with two of his former slaves: his cook Lydia Broadnax, 66, and a 16-year-old mulatto boy named Michael Brown. Wythe was convinced that blacks were as intelligent as whites and, given the same opportunities, would be just as successful.

Also living with him was his great-nephew George Wythe Sweeney, who was in line to inherit most of Wythe’s estate. The brash and irresponsible young man came and went as he pleased, and Wythe tried to exert a positive influence on him without much success. Sweeney was a regular at Richmond’s notorious gambling dens, and to pay his debts, he was not above selling books stolen from Judge Wythe’s library or forging his uncle’s name on checks. The judge finally threatened to cut his nephew out of his will if he didn’t change his ways.

On Sunday morning May 25, 1806, Wythe followed his usual routine at his home in Richmond’s fashionable Shockoe Hill neighborhood. He doused himself with a bucket of ice-cold water from the well in his backyard, then returned to his room to dress and read the newspapers until Lydia Broadnax brought him his breakfast of eggs, toast, sweetbread, and hot coffee.

Lydia carried the breakfast tray upstairs, and then returned to the kitchen to have a cup of coffee with Michael Brown. A few minutes later, she was stricken with horrific pains, and Brown collapsed on the table. Upstairs, Wythe finished his coffee and then vomited. When a doctor arrived to find all three in terrible agony, the judge raised himself up on the pillows of his bed and said in a hoarse whisper, “I am murdered.”

When Sweeney discovered that Wythe had willed part of the family property to Broadnax and Brown, Sweeney had poured arsenic into the coffee that Wythe, Brown, and Broadnax drank. Richmond’s three most renowned physicians, James McClurg, William Foushee and James McCaw, all showed up to tend to the members of the Wythe household.

The doctors were soon convinced that the symptoms exhibited by their three patients – sudden, severe stomach cramps, vomiting, diarrhea and acute pain – pointed to cholera. Cholera was often fatal within 48 hours, and as that deadline came and went, Broadnax began to recover, though the trauma she experienced permanently damaged her eyesight. Brown and Wythe remained in critical condition.

Wythe insisted that he and his housemates had been poisoned by his ne’er-do-well 18-year-old grandnephew. On June 1, Michael Brown died. Wythe lived on in agony for two weeks. Gravely ill and overwhelmed with grief, Wythe sent for his lawyer and wrote his nephew out of his will.

On June 2, Sweeney was arrested on forgery charges and incarcerated in the Henrico County jail. Wythe refused Sweeney’s request to post the $1000 bail.

George Wythe died from the poison Sweeney had given him on June 8, 1806, at the age of eighty, and Richmond prepared an elaborate funeral, the largest held in the state’s history to that time. Hundreds of somber official mourners – members of Congress, state legislators, judges and lawyers – crammed the statehouse on June 11 for the eulogy. Businesses in the city shut down for the day, and thousands of Virginians quietly lined Main Street as the funeral procession passed.

But one very important person was not in attendance: Because of slow mails, President Jefferson did not learn of his dear friend’s death until the day after the funeral. The president was also saddened by the death of Michael Brown, whom he had agreed to take in as a White House boarder if Wythe should die while the young man was still in his care.

Wythe was buried at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, where Patrick Henry made his “Liberty or Death” speech. Wythe bequeathed his treasured collection of books to President Jefferson, adding to the collection that would form the basis of the Library of Congress in 1815.

A grand jury indicted Sweeney for murder. Lydia Broadnax was thought to have been in the kitchen when the coffee was poisoned, but by Virginia law blacks could not testify against whites. Lydia was not allowed to tell the court that she saw Sweeney put something in the coffeepot the morning she and the others became ill.

That left the prosecution with a circumstantial case against Sweeney. After less than an hour’s deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. However, disinherited and dishonored, Sweeney soon left Virginia and was never heard from again.

George Wythe was perhaps the quintessential Founding Father. He was Virginia’s foremost classical scholar, dean of its lawyers, a Williamsburg alderman and mayor, a member of the House of Burgesses, and house clerk. He was the colony’s attorney general, a delegate to the Continental Congress, speaker of the state assembly, the nation’s first college law professor, and Virginia’s chancellor.

Thomas Jefferson wrote:

No man ever left behind him a character more venerated than George Wythe. His virtue was of the purest tint; his integrity inflexible, and his justice exact; of warm patriotism, and, devoted as he was to liberty and the natural and equal rights of man, he might truly be called the Cato of his country.

I had reserved with fondness, for the day of my retirement, the hope of inducing [Wythe] to pass much of his time with me. It would have been a great pleasure to recollect with him first opinions on the new state of things which arose soon after my acquaintance with him; to pass in review the long period which has elapsed since that time.

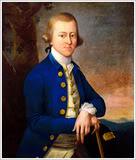

George Wythe Monument

The namesakes of William and Mary’s affiliated law school, John Marshall and George Wythe (right), stand proudly in front of the law school, now ranked 30th in the US.

SOURCES

George Wythe

George Wythe 1726-1806

Wikipedia: George Wythe

America’s Founding Fathers

Remembering George Wythe @ rpc.senate.gov

Robert A. Peterson: George Wythe of Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg: George Wythe

A Biography of George Wythe 1726-1806

Signer of the Declaration of Independence

The Mysterious Death of Judge George Wythe

The Classical Epitome of Colonial American Law