Wife of Declaration of Independence Signer James Smith

Eleanor Armor of Newcastle, Delaware, was born in 1729. She was described as “a young woman of many accomplishments and good family connection.” James Smith was born in Ireland, the second son in a large family, most likely in 1719, and came to Pennsylvania as a boy of ten or twelve years of age. His family settled in York County, Pennsylvania, on acreage west of the Susquehanna River.

His father was a successful farmer, and James received a good education at Reverend Francis Alison’s academy in New London, PA, where he learned Greek, Latin, and mathematics, including land surveying. He later studied law at the office of his older brother George, in Lancaster PA.

Smith was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar at age twenty-six, and set up an office in Cumberland County, PA, near Shippensburg, as a lawyer and surveyor. This was a frontier area at the time, so he spent much of his time engaged in surveying, only practicing law when the work was available. In about 1750, he moved to the more populated village of York, where he continued the practice of his profession for the remainder of his life. He was the first attorney to practice in York, and remained at the head of the bar of that county until after the Revolution.

Mr. Smith was quite an eccentric man, and possessed a vein of humor, coupled with a sharp wit and the gift of storytelling, which made him a great favorite in the social circle in which he moved.

Smith was endowed with wit and humor, given to storytelling and jovial companionship.

In 1760, when he was 41 years old, James Smith married Eleanor Armor, and they would have five children: three sons and two daughters. Only one of the sons and two of the daughters survived him. Their son James Smith, Jr. died a few months after his father’s death. The daughter, became the wife of James Johnson, a prominent citizen of York.

In the 1760s, Smith went into the Iron manufacturing on Codorus Creek, and lost a small fortune. He would later admit that he used poor judgment by placing the business in the hands of his two assistants, “one of who was a knave, and the other a fool.” Although he was the only lawyer in town until 1769, he experienced difficulty in recruiting clients. But by the beginning of the Revolution, he possessed considerable property.

For a long time, Smith did not show even a remote interest in politics, preferring to help raise his five children and develop his law practice. However, when the British Parliament closed the port of Boston for dumping tea in the harbor, in response to the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, Smith quickly emerged as an early Whig (Patriot) leader. Among his colleagues, he gained a reputation as a witty conversationalist and an eccentric.

Smith was now one of the few men in 1774 who made known his political position of cutting the bonds with England. At a provincial meeting in Philadelphia on June 15, 1774, he served on a committee that prepared a draft of instructions to this effect. He attended the Provincial Assembly, where he offered a paper he had written, called Essay on the Constitutional Power of Great Britain over the Colonies in America. In this essay, he suggested a boycott of British goods and the convening of a General Congress, as measures in the defense of the colonies’ rights.

As a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774, Smith actively supported the cause of American Independence. However, a large segment of Pennsylvania colonists, particularly the large body of Quakers, were strongly opposed, not only to war, but to a declaration of independence.

The instructions given to the delegates stated that “though the oppressive measures of the British Parliament and administration have compelled us to resist their violence by force of arms; yet we strictly enjoin you, that you, in behalf of this colony, dissent from and utterly reject any proposition, should such be made, that may cause or lead to a separation from our mother country, or a change in this form of government.”

This stand against a declaration of independence, roused the supporters of that measure throughout the province. The Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in May 1775, and they declared themselves the new government of the colonies. They appointed George Washington Commander in Chief of the newly organized Continental Army, and named other general officers.

Smith was also a member of the York Committee of Safety, and upon hearing the news of fighting at Lexington in April, 1775, organized a volunteer militia company in York, first volunteer company of militia raised to oppose the British in Pennsylvania. He was elected colonel, but because of his advanced age of 55 years, he was forced to decline.

In May 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia proposed a resolution, “That these colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states…” Because there was still too much hesitancy on the part of some delegates, particularly from Pennsylvania, it was decided to table this resolution. This allowed the pro-independent minded to convince the fence-sitters of the futility of reconciliation with England. Some reluctant delegates began to take the side of independence, and Pennsylvania elected new delegates to the Continental Congress. Among them was James Smith.

Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was brought up again to the Congress on July 1, 1776, and it was approved the following day. The Congress spent the next two days discussing the details in the language that had been prepared by a five-man committee, but much of it actually written by Thomas Jefferson. On July 4, 1776, the delegates agreed on the language in the Declaration of Independence. On his July 6, 1776, trip to York, James Smith carried with him a printed copy of the Declaration. A quality copy was embossed and this famous document was signed by the 56 delegates on August 2, 1776.

James Smith’s Signature

On the Declaration of Independence

Now that America had separated from Britain, each state needed a constitution for governance. King George III was no longer the authority. In July 1776, a convention was assembled in Philadelphia, for the purpose of forming a new constitution for Pennsylvania. James Smith was elected a member, and he appeared to take his seat on the July 15.

Throughout the summer of 1776, Smith and other delegates from York County worked with representatives from other counties on such a framework in Philadelphia. In late September, they put it in place. With Smith’s signature affixed, Pennsylvania now could point to a governing document. Local and county governments, in turn, had to reorganize from scratch under the authority of this constitution.

James Smith was in the Continental Congress from 1775 to 1778, and some of the letters Smith wrote to his wife while in Congress have been preserved. Through them all runs a vein of humor, an air of affectionate comradeship, and confidence in her ability to take care of their home affairs.

Letter to Eleanor from Philadelphia in October 1776:

…If Mr. Wilson should come through York, give him a flogging, he should have been here a week ago. I expect, however, to be home before election, my three months are nearly up… This morning, I put on the red jacket under my shirt. Yesterday, I dined at Mr. Morris’s and got wet going home, and my shoulder got troublesome, but by running a hot smoothing iron over it three times it got better this is a new and cheap cure. My respects to all my friends and neighbors, my love to the children.

I am your loving husband,

James Smith

The “Mr. Wilson” referred to above was his brother congressman, James Wilson, who had been attending court duties in Carlisle.

Letter to Eleanor dated September 4, 1778, ends with this paragraph:

You, my dear, have been fatigued to death with the plantation affairs; I can only pity but not help you… I have not time to finish, but you will have had nonsense enough,

Your loving husband,

James Smith

Until January 18, 1777, the names of the signers, other than the actual John Hancock, were not known for fear of reprisal. Emboldened by Continental Army victories in the battles of Trenton and Princeton, Congress ordered a second printing of the Declaration. A copy was sent to each state, and the names of James Smith and other signers became widely known.

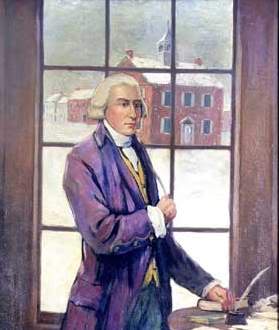

In his South George Street law office, used for the meetings of the Board of War during the Continental Congress’s nine-month visit to York, from September 30, 1777, to June 27, 1778.

On September 26, 1777, the British occupied Philadelphia. In anticipation of their arrival, the capital was abandoned by the Patriots and many in the business community. The Founding Fathers fled from the State House in Philadelphia to the Court House in remote York, PA, and the wide Susquehanna River flowed between America’s most wanted and the redcoats when the Continental Congress convened for the first time in York on September 30, 1777.

James Smith and 25 other signers of the Declaration would walk the town’s streets and meet in its Centre Square courthouse for the next nine months. There, they debated and eventually adopted another document that would complement the Declaration – the Articles of Confederation, America’s first framework of government.

The meetings of the Board of War were held in James Smith’s office on George Street. The Board, which was established to aid General Washington in opposing the progress of British General William Howe’s army, included George Clymer, Samuel Chew, James Wilson, and Richard Stockton.

The British position in Philadelphia became untenable after France’s entrance into the war on the side of the Americans. The occupying British feared an attack from the French armada and quickly abandoned the city on June 18, 1778, leaving the Tories unprotected and frightened. To avoid the French fleet, General Clinton was forced to lead his British-Hessian force to New York City by land.

James Smith retired from the Congress in November 1778, and returned to the practice of law. He was named a member of the Pennsylvania State Assembly the following year. From then until 1782, he held various State offices: judge of the Pennsylvania High Court of Errors and Appeals, Brigadier General in the militia, and State Counselor during the Wyoming Valley land dispute between Pennsylvania and Connecticut.

In 1785, he turned down reelection to Congress because of his age. His major activity prior to his retirement was the practice of law. In 1800, at the age of 81, he withdrew from the bar, having practiced of his profession for sixty years. He was said to be the oldest lawyer in Pennsylvania. In 1805, a fire destroyed his office and many of his papers.

James Smith died at York on July 11, 1806, at the age of 87, and was buried in the cemetery of the First Presbyterian Church in York.

Eleanor Armor Smith died July 3, 1818, and was buried beside her husband.

James Smith’s Grave

First Presbyterian Memorial Gardens

SOURCES

James Smith

James Smith (delegate)

James Smith 1719 1806

Biography of James Smith

James Smith: Pennsylvania

Smith Brought the Declaration to York

Biography of Eleanor Armor Smith

Religious Affiliation Of James Smith

Representing Pennsylvania at the Continental Congress

James Smith: Signer of the Declaration of Independence