Loyalist in the American Revolution

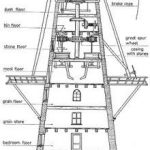

Image: Growden Mansion

Bensalem, Pennsylvania

Joseph Growden built this home which was later expanded upon by his son Lawrence, Grace Growden Galloway’s father. Grace later inherited this home, but since married women at that time were not allowed to own property, her husband Joseph Galloway automatically became the owner.

One of the most interesting diaries written during the American Revolution was written by Grace Growden Galloway, while the world as she had known it was completely destroyed. Her family history was typical of colonial American families. Her grandfather settled in Pennsylvania and accumulated a large amount of property. His second son Lawrence sought his fortune as a merchant in England, where he got married. Lawrence’s second child, Grace, was born in England in 1727.

After Lawrence Growden returned with his wife and two daughters to Pennsylvania in 1733, he served as a provincial councilor, a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly, and speaker of the assembly. In 1750, he was appointed second justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, a position he held for fifteen years. After his father’s death, Lawrence Growden inherited land holdings valued at about £113,400, becoming one of the richest and most influential men in the colony.

Her family’s wealth and social standing made Grace Growden attractive to many suitors in Pennsylvania, but she had a mind of her own. In 1747, while she was in England visiting her elder sister Elizabeth, she fell in love with a Mr. Milner, son of the receiver of customs at Poole. In 1751, Grace’s father heard about her attachment to Milner, deemed him unsuitable, and ordered Grace to return home.

Joseph Galloway was born in 1731 at West River, Maryland, to Quaker parents, and moved with his father to Pennsylvania in 1740, where he received a good education. Like the Growdens, the Galloway family had risen to wealth and prominence in the New World in less than 100 years. Joseph Galloway’s great-grandfather, a Quaker, immigrated to Maryland in 1662. By the time Joseph was born, his family had large land holdings and a mercantile business.

When Joseph inherited his father’s property, he moved to Philadelphia, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1749. He established a flourishing legal practice and purchased a spacious mansion at Sixth and Market Streets, and soon became one of the most prominent and wealthy lawyers in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

Grace Growden married Joseph Galloway October 18, 1753, at Philadelphia. They had two children: Joseph Lawrence Growden Galloway born in 1757, and Elizabeth Galloway born in 1761.His marriage to Grace enhanced his social and financial position and gave him entrée into politics. Some biographers have implied that the handsome, successful, and ambitious Galloway viewed the marriage as part of his ascent to the highest ranks of Philadelphia society. A Quaker, Galloway converted to Anglicanism in order to marry Grace, and his conversion enhanced his political career.

Joseph and Grace prospered, but as author Elizabeth Evans has indicated, both husband and wife were “strong-willed, and their marriage was a turbulent one.” They had three sons and one daughter, Elizabeth – the only one of their children to live to an advanced age. It is evident from the diaries that Elizabeth (Betsy) was the apple of her mother’s eye.

Despite their worldly success, Grace Galloway’s poetry includes indications that she was unhappy. In 1759, she wrote “[I] find myself neglected, loathed, despised.” Other poems describe male tyranny and a “wretched wife / whose doomed with him to spend her Life.”

In one poem she warned:

“Never get tied to a man

for when once you are yoked

‘Tis all a mere joke

of seeing your freedom again”

Prelude to Revolution

Despite the volume of opposition to British actions during the 1760s and early 1770s, not all Pennsylvanians were willing to support a revolution. Pacifist members of the Society of Friends (Quakers) and German sectarians opposed the War for American Independence on religious grounds. Some wealthy merchants and landowners feared the loss of social and economic status if their connection to British aristocrats were severed. Others advocated postponing military action, in the hope that further negotiations could resolve the divisive issues.

A member of the American Philosophical Society and its vice president from 1769 to 1775, Joseph Galloway made his mark in intellectual and social circles, and he shaped history with his political activity. Galloway formed a political partnership with Benjamin Franklin that controlled Pennsylvania politics from 1756 until the eve of the American Revolution.

Galloway served in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives from 1757 to 1775. From 1766 to 1775, he dominated politics as speaker of the assembly. During the early part of the colonial struggle, he exhibited sympathy for the crown, and adopted Loyalist sentiments in the early 1770s. He grew to be an active Tory (British supporter). Through his influence as speaker of the assembly, he had himself chosen to the Provincial Congress, with the purpose of influencing that body in favor of the king.

Galloway was also one of the richest men in the colonies. During the 1770s, Grace inherited Trevose (444 acres), Belmont (574 acres), King’s Place (297 acres), Richlieu (407 acres), a Delaware river tract (160 acres), and 30 percent of the Durham Iron Works, and her wealth further enhanced their financial position.

Image: Joseph Galloway

Galloway was a delegate from Pennsylvania to the First Continental Congress, which met from September 5 to October 26, 1774. The Congress was attended by 56 members appointed by the legislatures of twelve of the thirteen colonies – Georgia did not send any delegates. The Congress met briefly to consider an economic boycott of British trade, to publish a list of rights and grievances, and to petition King George for redress of those grievances.

At the Congress, Joseph Galloway opposed independence for the American colonies. He introduced a sweeping plan that was intended to reconcile problems between the colonies and the mother country. His plan provided for (1) an American Grand Council elected by the colonial legislatures and possessing wide powers over intercolonial political affairs, (2) a president general appointed by the Crown, and (3) a mutual veto by Parliament and the Council over legislation passed by either affecting the Colonies.

The plan was not only rejected, it was expunged from the published proceedings of the Congress. Embittered, Galloway refused to serve in the Second Congress. He retired to his home, where Ben Franklin visited him, and tried in vain to win his support for Colonial rule.

The colonists’ at the Second Continental Congress convened the following year to organize the defense of the colonies. After they issued the Declaration of Independence in early July, 1776, Galloway, fearing for his safety, fled to the British camp in New Brunswick, and remained loyal to the King. Thus, Grace became the wife of a prominent Loyalist, who was considered one of the greatest traitors to the American cause.

In December 1776, Galloway went to New York and joined the British Army. There he became an advisor to General William Howe, telling him inaccurately that 90 percent of Americans would support suppression of the Revolution. Galloway accompanied General Howe when he occupied Philadelphia in September 1777.

During the British occupation, Galloway was appointed Superintendent of Police and Superintendent of the Port, which gave him a vast array of powers that he used against the rebels. He had a reputation as a highly efficient administrator, but one who repeatedly interfered in military affairs. He aggressively organized the Loyalists in the city.

The Pennsylvania Assembly passed an act of attainder on March 6, 1778, that required alleged Loyalists to face trial or risk forfeiture of their estates. The Assembly hoped to pay the cost of government and the war with funds produced by the sale of Loyalists’ property.

Abandoned in Philadelphia

When General Howe resigned, the new British commander, General Henry Clinton, moved the army from Philadelphia to New York in June 1778. Fearing for his safety, Galloway fled behind the British lines taking with him their only surviving child, Betsy. In October 1778, they sailed for London, where he continued to urge the British to put down the rebellion. They assumed that the British would prevail.

Grace Galloway stayed behind, like many Loyalist wives, to save their property, and to claim the land she had inherited from her father, which she hoped to pass on to Betsy. All she needed to do in her family’s absence was to retain control of their property and business interests, and she initially relied on her husband’s friends and business partners for advice.

Grace wrote her diaries during the years 1778 and 1779, while she remained alone in Philadelphia to fight for legal recognition of her right to her own property. But the Pennsylvania Assembly convicted Galloway of high treason, and Grace soon learned that all of their property had been confiscated, and she would soon be evicted from her home.

After Revolutionaries confiscated her house in September 1778, Grace pursued a campaign to protect her inherited properties, totaling over 1,800 acres. Pennsylvania authorities eventually ruled that she could not control her land inherited from her father until after her husband’s death. Only after Joseph’s death in 1803 was Betsy able to inherit the land.

Grace worried over the fate of her daughter and husband, from whom she received letters infrequently. Correspondence she received from them on May 4, 1779, left her feeling “more easy as I hope from what they write we shall not sink, and they are well and happy.” Grace also feared the potential for violence against Loyalists. One night she “awoke early in a fright, dreamed I was going to be hanged.” The earlier hanging of Loyalist George Spangler must have made an impression on her.

Although Grace socialized daily with an extensive network of female friends, she confided her fear and isolation to her diary. After Grace was evicted from her house, she boarded with Quaker Deborah Morris. While she lived with “dear Debby,” a steady stream of visitors came to take tea with the two women, although these visits were not always to Grace’s liking. During one visit, she and an acquaintance “had a dispute” over whether Britain or America was better. “We got at last very earnest and hated each other freely.” Politics and war invaded women’s social gatherings and tested Grace’s Loyalist sympathies.

Grace had to make arrangements for basic daily needs with devalued Continental currency. In her diary, she described the arduous process of purchasing firewood, salt, cider, and other necessities. She resented other changes too, writing late in 1778, “My dear child came into my mind and what she would say to see her Momma walking five squares in the rain at night like a common woman and go to rooms in an alley for her home.”

Grace was not alone in her struggles. Many Loyalist wives stayed in the colonies to protect property; sometimes their husbands abandoned them, as Joseph Galloway seems to have done. As it became clear there was little hope of acquiring title to their American properties, Grace wrote: “I am determined to go from this wicked place as soon as I hear from JG [Joseph Galloway], and not by my own impatience put it out of my power to leave this Sodom…”

But Grace received no instructions from her husband. Her poor health and precarious financial situation frustrated her in the final months of her diary: “All is cloudy and I am wrapped in impenetrable darkness, will it, can it ever be removed, and shall I once more belong to somebody, for now I am like a pelican in ye Desert.”

As is the case with so many women of her era, most of Grace Galloway’s biography has been inferred from information about her male relatives. She lived her life in the shadow of men, and derived her sense of self from her position as the wife of one of the most important men in Pennsylvania.

Even when she felt scorned by society and abandoned by friends, she asserted her relationship to the male figures in her life as the sign of her own identity, and as a means of validating her right to privilege:

I told them I was ye happiest woman in town for I had been striped and turned out of doors, yet I was still ye same and must be Joseph Galloway’s wife and Lawrence Growden’s daughter, and that it was not in their power to humble me, for I should be Grace Growden Galloway to ye last, and as I had now suffered all that they can inflict upon me, I should now act as on a rock to look on ye wrack of others.

(April 21, 1779)

From England, Joseph Galloway attempted to persuade the Pennsylvania Assembly to return his property, but in vain. His petitions to return to America after the Revolution were denied as well, and he was never reunited with his wife.

Grace Growden Galloway died in Philadelphia in February 6, 1782.

In England, Joseph Galloway pled the loyalist cause for restitution from the Crown. In 1783, the British government granted him a sizeable annual pension of £500. He spent the rest of his years in exile in Britain, writing books like The Claim of the American Loyalists (1788), trying to justify his position.

Although histories of the American Revolution commonly celebrate the victors and the sacrifices of the Patriots, Grace Galloway’s diary reminds us that a large number of Americans paid a terrible price, especially wives of Tories, for opposing America’s War for Independence. Her experiences illustrate the challenges Loyalists faced when they remained in the colonies during the American Revolution.

Her wartime diary reveals how the absence of male family members and the hardships of military conflict transformed women’s daily lives. For Grace, American independence meant poverty, abandonment, loss of social precedence, and the devastating disappearance of the prewar world she had known. In time, some of Grace’s lands were restored to her daughter Betsy.

Joseph Galloway died August 29, 1803, at Watford, England, a pensioner of the Crown and an object of scorn to his countrymen.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Joseph Galloway

Joseph Galloway, Plan of Union

The Claim of the American Loyalist