Wife of General John Stark

Image: Molly Stark Statue

One of Wilmington, Vermont’s most prominent landmarks is the statue of Revolutionary War heroine Molly Stark. Her descendants donated the statue to mark the center of the Molly Stark Trail, which crosses southern Vermont and is thought to be the route taken by General Stark on his victory march home from the Battle of Bennington. To confuse the enemy, General Stark referred to the route they were taking as the Molly Stark Trail, and it is identified as such on the official Vermont Highway Map.

Early Years

Elizabeth (Molly) Page was born February 16, 1737, in Haverhill, Massachusetts. Around 1755, she moved with her family to Dunbarton, New Hampshire. Her father, Caleb Page, was the first postmaster of New Hampshire.

John Stark was born in Londonderry, New Hampshire, on August 28, 1728. When he was eight years old, he and his family moved to Manchester. His father had emigrated from the north of Ireland and settled on the extreme frontier of New Hampshire, near the local Indians. He owned extensive tracts of land, and was an original proprietor of Dunbarton.

Growing up in a frontier community gave John Stark the skills he would use later as a military leader. Hunting, fishing and scouting were among the pioneer activities necessary for survival in the harsh wilderness. Stark’s first military action was during the French and Indian War (1754 – 1763), when he was appointed a lieutenant in Major Robert Rogers’ famous corps – Rogers’ Rangers.

Rogers’ Rangers were an independent colonial militia company attached to the British Army during the French and Indian War. The unit was trained as a rapidly mobile light infantry force tasked with reconnaissance and special operations. Stark and his comrades picked up new strategies from their Indian allies and their enemies that helped them fight the British during the Revolutionary War.

In 1758, hearing of his father’s death, Stark obtained a leave of absence to come home to help settle the estate. At this time, he was a frequent visitor to the Page homestead in Dunbarton, New Hampshire. Molly Page married John Stark on August 20, 1758. Together they had eleven children.

John and Molly settled in the Page home, but after a few weeks of inactivity, Stark eagerly responded to General Amherst’s request to build a road from Crown Point to Fort No. 4, Charlestown. It soon became apparent that resentment of the British was building. The Rangers were consistently made to feel inferior to the British. Army discipline was severe and unyielding.

At the end of the French and Indian war, John retired from the army. Marriage and his farm and mill occupied his attention for the next sixteen years. His father’s estate settled, he bought the land his brothers and sisters had inherited, and became sole owner of a substantial estate near Manchester, New Hampshire.

Image: John and Molly Stark House

Manchester, New Hampshire

The Revolutionary War

Resentment of the British following the French and Indian Wars came to the surface as King George imposed more and more taxes on the colonies. The Stamp Act of 1765, the Boston Massacre of 1770, the tea tax resulting in the Boston Tea Party of 1773 – all were sparks helping ignite the conflagration which would soon envelop the colonies.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, signaled the start of the war. On April 23, John Stark was appointed colonel of a regiment of New Hampshire militia, and was given command of the 1st New Hampshire Regiment. The militia was created to protect the colonies from attacks by the French and their Indian allies, and had more at stake than those serving in the regular army; they were protecting their homes and families.

Stark and his men were dispatched to aid the militias of Massachusetts, who were trying to keep the British in Boston. When the British tried to push out of Boston by attacking the colonists, the colonists fought valiantly at the Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775). John Stark and his men filled a gap in the lines, and held off the British longer than expected, due mainly to John Stark’s strategy and encouragement.

After the Battle of Bunker Hill , as General George Washington prepared to return south to fight the British there, he knew that he desperately needed experienced men to command regiments in the army. Washington immediately offered Stark a command, and Stark and his New Hampshire regiment agreed to attach themselves temporarily to the Continental Army.

After the British evacuated Boston on March 17, 1776, Stark marched with his regiment to the New Jersey colony with General Washington and fought bravely in the Battles of Trenton (December 26, 1776) and Princeton (January 3, 1777).

After Princeton, Washington asked Stark to return to New Hampshire to recruit more men for the Continental Army. Stark was in a cheerful mood as he traveled around the settlements, talking to farmers and townsmen. But he soon learned that while he was fighting in New Jersey, a fellow New Hampshire Colonel Enoch Poor had been promoted to Brigadier General.

Enoch Poor had refused to march his militia regiment to Bunker Hill to join the battle, instead choosing to keep his regiment at home, and Stark believed he had been passed over for promotion by someone with no experience and apparently no will to fight. On March 23, 1777, Stark resigned his commission in disgust. In spite of urgent efforts to get him to reconsider, Stark remained adamant, though he pledged his aid to New Hampshire should it be needed.

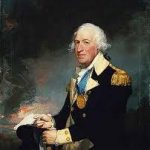

Image: General John Stark

Battle of Bennington

In July 1777, John Stark was offered a commission as Brigadier General of the New Hampshire militia. He consented on condition that he be answerable only to New Hampshire. Stark led his men to meet the British at Bennington, Vermont, where British General John Burgoyne had dispatched Colonel Frederick Baum with 500 men to seize American storehouses to restock their depleted provisions.

Sending out expresses to call in the local militia, Stark assembled approximately 2200 men – some 1400 came from New Hampshire, 600 from Vermont and the balance from New York, Massachusetts and Connecticut. The volunteers were mostly farmers and townspeople. There was no time for training, and no money for uniforms or weapons. The volunteers left their businesses and farms wearing their usual clothing and often carrying their own guns.

Stark and the militia marched out to meet Baum, who had entrenched himself in a strong position and sent to General Burgoyne for reinforcements. Before reinforcements could arrive, Stark attacked Colonel Baum on August 16, 1777. Prior to attacking the British and Hessian troops, Stark prepared his men to fight to the death. Molly Stark became a legend thanks to her husband’s battle cry:

There are your enemies, the Redcoats and the Tories. They are ours, or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow!”

Stark’s men, with some help from Seth Warner’s Vermont militia, the Green Mountain Boys, routed the Hessian forces there. A second British force of 500 men, under Colonel Breymann, presently arrived on the scene, and were also totally defeated. Of the 1,000 British, not more than a hundred escaped, all the rest being killed or captured. The American loss was only about seventy.

Colonel Baum, who was mortally wounded, said of the militiamen: “They fought more like hell-hounds than soldiers.” Washington spoke of it immediately as “the great stroke struck by General Stark near Bennington.” Loyalist Baroness Riedesel, then in the British camp, wrote: “This unfortunate event paralyzed our operations.”

John Stark became widely known as the Hero of Bennington for his exemplary service. Stark’s decision to stop the British advance at Bennington prevented Burgoyne from resupplying, and contributed directly to Burgoyne’s surrender on October 17, 1777, after two unsuccessful battles in Saratoga.

A grateful Continental Congress raised Stark’s rank to Brigadier General in the Continental Army two months after Bennington. The war dragged on for six more years. Stark sometimes took part, but when cold weather set in, he sometimes went home to recuperate from the attacks of rheumatism that were to plague him the rest of his life. He fought in several decisive battles, and achieved a reputation as a leader and shrewd tactician. He was popular with his men, and his success was due to his independence and decisiveness.

Later Years

In 1783, John Stark was ordered to headquarters by Washington, and given the personal thanks of the Commander-in-Chief and the rank of Major General. Following this promotion, he retired to his farm in Manchester, New Hampshire. He and Molly then had ten children, five boys and five girls, having lost one daughter in infancy.

When he was 89 years old, Congress allowed General Stark a pension of sixty dollars per month; but with his simple tastes, this was not essential to his comfort. He was a good type of the class of men who gave success to the American Revolution.

In 1809, a group of Bennington veterans gathered to commemorate the battle, and General Stark, then aged 81, was asked to speak at the celebration. He was not well enough to travel, but he sent a letter to his comrades, which he signed: “Live free or die. Death is not the worst of evils.”Live Free or Die became the New Hampshire state motto in 1945.

Molly Page Stark died of typhus in 1814, aged 78. John was 86, and he slept that night a widower.

General John Stark died on May 8, 1822, at the age of 94, reportedly the last surviving Continental general of the American Revolution. He was buried with military honors on May 10, 1822.

The location of the little cemetery that contains his remains was selected by him for a family burial place several years before his death. The site is a commanding plateau, overlooking the Merrimack River within the boundaries of what was then his farm.

The Molly Stark Cannon

The famous Molly Stark cannon, named for the general’s spirited wife, was captured from the British at the Battle of Bennington by New Hampshire troops under the command of General John Stark. The cannon had been cast in Paris in 1743, and ornately decorated with a shield and crown flanked by American Indians armed with bows and arrows.

The cannon served in defense of the British siege at Detroit, Michigan, during the War of 1812, and was recaptured by the British after the surrender of the city. The Americans captured it from the British once again at the Battle of Fort George during the same war.

Prior to his death in 1822, General John Stark removed the cannon from storage at the first arsenal built by the United States in Watervliet, New York. Old Molly was retired from active duty and presented to the New Boston Artillery Company of the 9th Regiment of the New Hampshire Militia by General Stark for the company’s contributions to the success of the Battle of Bennington. Old Molly is fired every year on July 4th.

Molly Stark, one of our Founding Mothers, is also known for her success as a nurse to her husband’s troops during a smallpox epidemic, and for turning her already-crowded home into a makeshift hospital for ailing soldiers during the war.

SOURCES

Molly Stark

General John Stark

John Stark Biography

Wikipedia: John Stark

John Stark (1728 – 1822)

Molly Stark (1737 – 1814)

John Stark: Maverick General

Does anyone know anything about an adopted daughter, Nabby Neaby Abigail Smith who married Robert McCauley?

I think I’ve found her.

Hi, Abigail is my husband’s ancestor. I came across reference from a McCauley family history that claims she was adopted by Stark and was his niece. Unfortunately, I haven’t found more than that. Since you wrote this comment in 2017, I’m wondering if maybe you’ve found the relevant information?