Early Incident in the American Revolution

Image: The Burning of the Gaspee

Painting by Charles DeWolfe Brownell

At the end of the Seven Years’ War, following Britain’s decisive victory, several successive ministries implemented reforms in an attempt to achieve more effective administrative control and raise more revenue in the colonies. The revenue was necessary, Parliament believed, to bolster military and naval defensive positions along the borders of their far-flung empire, and to pay the crushing debt incurred in winning the war on behalf of those colonies.

The Newport, Rhode Island area has a long and interesting local history, and since 1741 the town’s tradition has included the Newport Artillery Company, the oldest continuous commissioned military unit in the United States. The company was formed under the terms of a charter granted by King George II of England, and the formation of the company.

This was in keeping with the colonial pattern of local defense forces made necessary by the initial British policy of salutory neglect of the colonies. Salutory Neglect was the hands-off policy with which England governed the American colonies during the 1600s and through the mid-1700s – a policy of avoiding strict enforcement of parliamentary laws meant to keep the American colonies obedient to Great Britain.

Between the end of the French and Indian War (1763) and the Declaration of Independence (1776), Rhode Island was sharply divided into Loyalists and Patriots, caused by the Great Britain’s desire to assess taxes and station permanent garrisons in the colonies. Some of the colonists, accustomed to local rule, desired neither. In general, the prominent landowners, especially those whose holdings were based on royal charters, remained loyal to the King, while the merchants and small farmers were in the Patriot camp.

The Rhode Islanders were especially irritated by the British customs laws and the efforts to enforce them. The British Government stationed the Gaspee in Newport harbor to collect taxes at gunpoint from every vessel that entered the harbor. More than half of all Rhode Island vessels were engaged in smuggling tea, which meant that every ship would be in danger. The bay had many coves and inlets and many of them offered ideal cover to seamen determined to thwart London’s Acts of Trade and Navigation.

Lieutenant William Dudingston first came to the attention of America in September 1768, when he took over command of the much-hated HMS Gaspee. During this change of command, the Gaspee was refitted from a single masted sloop to a twin masted schooner. Lt. Dudingston and his fellow officers had strict orders and generous financial incentives to prevent illegal smuggling along the American coast. British legislation deputized these officers as customs officials, and they were awarded a share of the value of any illicit cargo seized by them.

In February 1772, Lt. Dudingston sailed the Gaspee into Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay to aid in the enforcement of customs collection and the inspection of cargo. Rhode Island had a reputation for smuggling and trading with the enemy during wartime, and Dudingston and his officers quickly antagonized powerful merchant interests in the small colony.

Dudingston immediately stopped and seized one of the packet sloops owned by the powerful Greene family of East Greenwich, and he and his crew proceeded to beat up its commander, Rufus Greene. Dudingston condemned the sloop and her cargo as a prize of customs enforcement, and sent the boat to Boston to be sold by the Admiralty based there.

This incensed the seafaring citizens of Rhode Island. The Gaspee crew was even ordered to take supplies from area farmers without permission or compensation. When news of these actions reached Rhode Island Governor Joseph Wanton, he called for a meeting with Lieutenant Dudingston to voice the residents’ concerns.

Dudingston refused to attend and continued his strategy of disrupting commerce throughout Narragansett Bay. He pursued every ship from the large merchantmen to the small traders and fishermen, and continued to incite the colonists.

The packet sloop Hannah, under the command of Captain Benjamin Lindsay, had properly passed customs inspection at Newport. When Dudingston and his crew gave chase, Lindsay deliberately lured the Gaspee across the shallows off Namquid Point, and the British ship ran aground on a sandbar, and would be unable to move until the flood tide of the following day.

Upon arrival in Providence, Captain Lindsay alerted officials in Providence to the Gaspee ‘s mishap, a town crier was sent out inviting all interested parties to a meeting at Sabin’s Tavern to decide on a course of action.

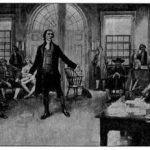

Shortly before midnight on June 9, 1772, 64 armed Rhode Islanders in eight longboats with muffled oars rowed out to the stranded ship. John Brown, a leading Providence citizen, called for the surrender of the Gaspee and Lieutenant Dudingston. In response, Dudingston ordered the crew to fire upon anyone who attempted to board the ship.

The majority of these men, who comprised the social elite of Providence, were disguised with black-smeared faces or Indian headdresses. Led by John Brown, a wealthy merchant and member of one of Rhode Island’s most prestigious families, their intentions were nothing less than the deliberate destruction of the government ship on duty in Narragansett Bay.

Shortly thereafter, the Rhode Islanders rushed the decks of the Gaspee and, in the melee, Dudingston was shot in the arm and fell to the deck – marking the first bloodshed for American independence. The remainder of the crew, most of whom were asleep below deck, were overcome by the raiding party, and the ship was forced to surrender.

The captured crew was bound, placed into the longboats, and put ashore at Pawtuxet Village nearby, and Dudingston was taken to the house of Joseph Rhodes. Lieutenant Governor Sessions visited Dudingston there the following day, but he refused to talk about his experiences. He was tended to for a few days by the well known local physician, Henry Sterling.

The colonists rowed away with their prisoners, leaving one boat and the leaders of the expedition – prominent men of Providence – who removed most of the documents aboard the ship, and ordered Gaspee to be burned, and the vessel burned to the waterline. At the break of dawn on June 10, 1772, the ship’s powder magazine exploded, and the Gaspee sank, utterly destroyed.

The Brentons of Newport

Lt. Dudingston was later moved to the home of Mr. and Mrs. Jahleel Brenton at Newport, because it was thought to be safer there. He stayed at their home during the early part of his recovery from his wounds. He spent several weeks recuperating at their home, and a marine guard was stationed outside Brenton’s house until Dudingston was well enough to travel.

The Brenton family was a prominent one in Rhode Island. Its founder, William Brenton, emigrated from England to Boston in 1633 with a commission to survey land for Charles I. Finding Boston’s religious atmosphere too intolerant, Brenton continued on to Providence, where he purchased the Island of Rhodes (Aquidneck) from the Indians through the agency of Roger Williams.

Brenton established the town of Newport, which soon became a prosperous trading community. His grandson, Jahleel Brenton, who held 2000 acres of land on Brenton’s Neck and who participated extensively in Newport’s profitable commercial enterprises, was one of its most prominent citizens.

Because of rumored threats to Dudingston, the Royal Navy took him under protective guard to the HMS Beaver, and in mid-July he was shipped back to Europe, reportedly continuing his recovery at a French spa.

The day after the burning of the Gaspee, everyone in Providence, Newport, Bristol, and other towns on the bay knew what had happened. They had seen the smoke, and many were aware of the fire and the explosions during the night. But, from June 10, 1772 until a year later, when the investigation of the Gaspee incident was closed, not one person admitted knowing the name of any person involved.

The British responded by stationing additional warships in the harbor, whose sailors kept the townspeople in continual alarm with their foraging and other indignities. The King of England offered $5000 reward for the leader of the expedition and $2500 for the arrest of any of the men who had been with him, but no one could be bribed or frightened Into betraying the patriots who had delivered their Colony from the hated Gaspee.

No further local investigation of the Gaspee incident took place. When the General Assembly met in August, its members approved of the actions that the Governor had taken and authorized him to continue the investigation in whatever manner he considered to be appropriate. Governor Wanton didn’t make an effort to discover or prosecute any individuals.

The news of the incident was well reported throughout the colonies, however. Newspapers from New Hampshire to South Carolina reprinted stories about it from the Providence, Newport, and Boston papers. The burning of the Gaspee was the first step toward the formation of the Committees of Correspondence, the convening of the Continental Congress, and the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

The attack on the Gaspee by Rhode Island patriots in 1772 came after almost ten years of growing conflict between the American colonies and their mother country. It ended a two year period during which, after the Boston Massacre of 1770, there were no major incidents of violence, and it had appeared that the difference might be settled peacefully.

But by the end of 1773, the Boston Tea Party had taken place. This time the British responded with immediate punitive measures instead of a fact finding commission. From that point on, revolutionary attitudes grew stronger until April 1775, when fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord.

SOURCES

Gaspee Days

Gaspee Affair

The Gaspee Affair

Research Notes on William Dudingston

Revolutionary Fire: The Gaspee Incident

The Burning of the Gaspee Near Pawtuxet Cove