Patriot in the American Revolution

Image: Sketch of the Old Chelsea Mansion

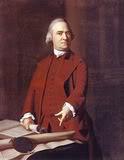

Charity Clarke was born June 28, 1747. Her father, Major Thomas Clarke, was a retired British veteran of the French and Indian War. He named his property in lower Manhattan Chelsea – at the time a country estate – for the soldiers’ hospital near London, and thus gave a name to the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City. The Clarke estate encompassed the area that is now 18th to 24th Streets between Eighth and Tenth Avenues in Manhattan. The Chelsea mansion was located at what is now Eighth Avenue and West 23rd Street, and Charity inherited the entire estate.

In her early 20s, Charity Clarke was a young New York City woman with strong opinions about the growing tensions caused by Great Britain’s tightening grip on the American colonies. Between 1768 and 1774, she wrote a series of letters to her cousin Joseph Jekyll, a London lawyer. These letters show her disdain for the policies of the English Monarchy and her growing sense of patriotism in the period leading up to the American Revolution.

Charity wrote on November 6, 1768, “When there is the least show of oppression or invading of liberty you may depend on our working ourselves to the utmost of our power.” What made her so angry was the landing in Boston a month earlier of a garrison of British soldiers to quell increasing disorders brought about by the Townshend Acts, which charged customs duties on a number of imports, including tea.

The Townshend Acts of 1767 wanted to strengthen the power of the British parliament, which would simultaneously strengthen the power of royal officials. He convinced the Parliament to pass a series of laws imposing new taxes on the colonists for lead, paint, paper, glass, and tea imported by colonists.

Colonial reaction to these taxes was the same as to the Sugar Act and Stamp Act, and Britain eventually repealed all the taxes except the one on tea. In response to the sometimes violent protests by the American colonists, Great Britain sent more troops to the colonies. In addition, the New York legislature was suspended until it agreed to quarter British soldiers. The Acts also insured that colonial officials, including governors and judges, would receive their salaries directly from the Crown.

Charity Clarke signed her letters, “Your friend and affectionate cousin,” but she could be slyly sarcastic when the occasion called for it:

What a pretty figure your expedition to Boston will make in history. They may now employ themselves in gathering of shells or what may please for they have nothing else to do. As to insurrections, we know of none. And unruly mobs we’ll leave to England, they don’t govern America.

On March 31, 1769, Clarke echoed a general sentiment among Americans: an accommodation with Great Britain, not a separation. One of the weapons being used by the colonies was a restriction on English imports, a tactic that caused many problems:

The attention of every American is fixed on England. The last accounts from thence are very displeasing to those who wish a good understanding between Britain and her colonies. The Americans are firm in their resolution of no importations from England. The want of money is so great among us that land sells for less than half price. The merchants have no cash to buy bills of exchange, which are now very low.

The following June, Clarke announced her readiness to join “a fighting army of Amazons,” who would take to take to the hills, if necessary, to flee the oppressive British:

If you English folks won’t give us the liberty we ask… I will try to gather a number of ladies armed with spinning wheels [along with men] who shall all learn to weave & keep sheep, and will retire beyond the reach of arbitrary power, clothed with the work of our hands, feeding on what the country affords… In short, we will found a new Arcadia.

By October 28, 1771, the Townshend Acts had been annulled, except for the tax on tea, but five Patriots had been killed by British soldiers in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. It was the culmination of civilian-military tensions that had been growing since royal troops first appeared in Massachusetts in October 1768, and anger was rising in the colonies.

Charity Clarke wore her patriotism on her sleeve:

Unaffected patriotism and true virtue will I trust distinguish America in every age, and among every nation. So my dear Coz, your fears are groundless. America still practices the thorough unboasted list of virtues, which the generality of English men have scarce an idea of.

Although King George III had become the symbol for everything wrong with late-18th century British colonial policy, Charity sympathized with him, reserving her barbs for the policies of the British Parliament, and the prime minister, Frederick, Lord North.

May 7, 1772:

How I pity the situation of our poor King, what with the death of his mother, the folly of his brother and the misfortunes (I hope not vices) of his sister. He has enough to overwhelm his heart with sorrow and embitter every enjoyment of life.

That spring, the latest scandal in London was that the King George III’s brother, 29-year-old William, had been for six years secretly married to a widow with three children. The king’s youngest sister, 21-year-old Caroline – who had married her first cousin, the disreputable King Christian VII of Denmark, when she was 16 – had long been the mistress of Christian’s court physician, Johann Struensee.

Months passed, and the situation in the American colonies worsened. As a result of the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, Parliament passed acts limiting the freedom of the colonists, especially in Massachusetts. The most significant result to come from the Boston Tea Party and Parliament’s reaction to it was the change of perspective for so many American patriots.

While the colonists considered some laws passed by Parliament to be biased and punitive, they still considered themselves loyal subjects who merely wanted a change in government policy toward the colonies. After the Boston Tea Party, more and more colonists began to believe that a new nation needed to be formed. Once that belief began to spread, it was only a matter of time until the colonies were in a state of open rebellion.

Charity’s last pre-revolutionary letter was dated September 10, 1774:

On what instance pray are the Americans called Rebels? What have they done to deserve the name? They have asserted their rights, and are determined to maintain them. Great Britain stands ready to destroy her sons for inheriting her spirit.

What care we for your fleets and armies, we are not going to fight with them unless drove to it by the last necessity, or the highest provocation… Though this body is not clad with silken garments, these limbs are armed with strength. The soul is fortified by Virtue, and the love of Liberty is cherished within this bosom.

A proud, ambitious Minister [Lord North] governs in Britain. By his sophistry makes the King deaf to the remonstrances of his subjects, by his bribery obtains the majority of Parliament, and by his power would spread tyranny to the western continent.

But its inhabitants are not sunk in luxury, nor are they clouded by pomp. Their eyes watch over their liberty, observe every encroachment and oppose it. And is this their crime in your eyes, my Cousin? Do you condemn them for not being foolish enough to give away the property of their posterity? Surely you ought not to condemn America.

The final pages of this letter are missing. Thus, abruptly ends Charity’s letters to her London cousin Joseph Jekyll on the eve of the American Revolution.

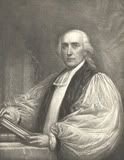

At the age of 32 – quite late in life to marry at that time – Charity Clarke married Right Reverend Benjamin Moore DD April 20, 1778, in NY. He was the second Episcopal Bishop of New York, Rector of Trinity Church, and President of Columbia College (now Columbia University).

Image: Benjamin Moore

Their only child, Clement Clarke Moore, was born on July 15, 1779, at his parents’ Chelsea estate, Clement Moore was educated at home in his early youth and graduated first in his class from Columbia in 1798. He became a respected biblical scholar, but is best-known for his poem, A Visit From St. Nicholas or The Night Before Christmas. The poem, written solely for the amusement of Moore’s own children, was read aloud for the first time one snowy Christmas Eve in 1822.

The poem seems to have its origins in the Dutch folklore of the area surrounding the Chelsea estate. Saint Nicholas had long been a folk figure in Holland, delivering presents to good children by leaving them on the doorstep or putting them through the window. It seems that Moore, with Saint Nicholas’s Dutch origins in mind, drew on the Chelsea House handyman – a fat, jolly old Dutchman – as the model for his version of St. Nick. Thus the image of a portly Santa was forever fixed in people’s minds.

Moore also gave St. Nicholas a sleigh (in Dutch legend he had traveled in a wagon), grounding his poem in local atmosphere by having the Saint utilize the type of vehicle used to travel during the snowy winters of the Hudson area. No one knows where the reindeer came from, but perhaps Moore felt that St. Nicholas deserved transportation more colorful than a mere horse-drawn sleigh.

Reverend Benjamin Moore died Feb 27, 1816, at Greenwich Village.

Charity Clarke Moore died December 4, 1838, at the age of 91.

SOURCES

Benjamin Moore

Clement Clarke Moore