Revolutionary War Heroine

When Rebecca Brewton was born June 15, 1737, her family had already lived in the low country of South Carolina for over half a century, and had established themselves as leaders in the Proprietary and Royal governments. Rebecca was the third daughter of Robert Brewton by his second wife, Mary Loughton Brewton. There was also a son, and three children by his first wife.

Rebecca was reared in an atmosphere of security, wealth, and intelligence. Her father was an imposing figure in Charles Town, where he served as church warden for St. Phillip’s Parish and Christ Church Parish, and was captain of one of the two militia companies.

Charles Town (later Charleston), South Carolina, was only thirty years old when the Englishman, Robert Brewton, and the Huguenot exile, John de la Motte, took up residence there. On June 28, 1758, Rebecca Brewton married Jacob Motte, grandson of the Huguenot. Of the seven children born to them, only three daughters lived to adulthood.

With the excitement of the times, the expanding economy of the colonies, and the desire for its political independence, Rebecca had a busy social life. The days brought important visitors to the Low Country, who were elegantly entertained by Rebecca and her family.

Rebecca’s brother, Miles Brewton, was a wealthy merchant and ardent supporter of the colony’s cause, and was very close to Rebecca and her family. Miles had been elected to the second Provincial Congress, and decided to take his family with him. On August 24, 1775, Miles, his wife, and three children set sail for Philadelphia. They were never seen or heard from again, and were listed as, “lost at sea.” The tragedy was difficult for Rebecca to accept.

Along with the Miles Brewton home in Charles Town, Rebecca inherited his plantation on the Congaree River in St. Matthews Parish, Orangeburg District, called Mount Joseph – and one of South Carolina’s largest fortunes. It was on this site that Rebecca chose to build a mansion.

During the troubled years preceding the American Revolution, Rebecca developed a keen interest in the problems of the Colony, and worked toward relieving hardships brought on by political unrest. She brought her entire plantation force down to work on the defenses that were being constructed around Charles Town. When war was declared, Rebecca threw all her energies and her means into war work, ministering to the needs of both soldiers and civilians.

First in 1776, and again in 1779, the British forces were unable to secure possession of the town. The third attempt, made by Sir Henry Clinton in 1780, was successful. For nearly three years, the town was in the enemy’s control. The Miles Brewton home was made headquarters by Clinton and his staff.

Restraining her personal feelings, though surrounded and sometimes insulted by the enemies of her country, Rebecca presided at her table day after day with calm dignity, yet in such a manner that these invaders of her country never doubted her patriotism.

The Mottes were crowded into a small area, while the British lived in comfort in the large rooms. Rebecca divided her time between the invaders, her invalid husband and her three young daughters, who were not allowed not allowed out of their rooms while the British were in the house.

In the fall of 1780, Rebecca Motte was given permission to leave Charles Town and return to Mount Joseph Plantation on the Congaree River, located midway between Charles Town and Columbia. The plantation was located on a high bluff, overlooking the river near the Charles Town to Rocky Mount Road.

Rebecca Motte was at Mount Joseph Plantation with her three daughters and niece-in-law Mrs. John Brewton, when the British forces seized the mansion, making it a military post. They threw up earthworks and dug a deep ditch around the house, and called it Fort Motte. It was held by British Lt. Donald McPherson with over 150 men.

Again the family were crowded into a few rooms, while British officers occupied the remainder. With the appearance of American forces in the area, the British ordered Motte to gather what belongings she wanted and move to her overseer’s house nearby – a rough structure, covered with weather-boards, and only partially finished. Jacob Motte died in January 1781.

After General Nathanael Greene returned to South Carolina with his Continental Army, he had reinforced General Francis Marion’s brigade with Lt. Col. Henry Light Horse Harry Lee (father of Robert E. Lee) and his Legion. The task of this combined force was to capture and destroy the line of British forts that protected communications and supplies between their Charles Town headquarters and the interior of South Carolina, one of which was Fort Motte.

Fearing that British reinforcements were on the way, Marion and Lee decided they must attack at once. The best way seemed to be to set fire to the mansion house and burn the British out. When they told Rebecca, she responded, “Do not hesitate a moment, I will give you something to facilitate the destruction.” She handed General Lee a quiver of arrows from the East Indies which, so she had been told, would set fire to any wood.

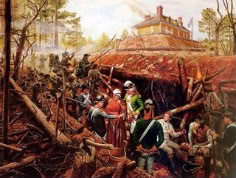

The combustible arrows were fired from a musket; two of them sputtered out, but the third one hit its mark and set fire to the roof of the house. The British, coming out of the attic dormer windows to put out the flames, were easy targets for the riflemen and six-pound cannon. They were quickly driven back inside, and the British captain ran up the white flag, fearing they would be blown up if the gunpowder stored in the house were set on fire. Together, British and American soldiers put out the flames.

Image: Capture of Fort Motte

Mort Kunstler, Artist

In this oil painting, the artist depicts the critical moment when arrows dipped in pitch set the roof of the Motte home ablaze and another arrow is about to be lighted. The gallant Light Horse Harry Lee consoles Rebecca Motte in the trenches, while Marion shows his mute concern.

That noon, Rebecca served dinner to the American officers and their British captives, after which the British, paroled on oath not to fight again, marched off to join the approaching reinforcements. In later years when Rebecca was praised for her part in the siege, she always said, “Too much has been made of a thing that any American woman would have done.”

Marion’s brigade remained in action for fifteen months after the capture of Fort Motte as fighting continued in South Carolina. In December, 1782, when the British finally evacuated Charles Town, Marion’s brigade was disbanded.

After the Revolutionary War, Rebecca Motte returned to her home in Charles Town. As a result of the war, her estate became heavily encumbered with debt, but she showed her strong character, and her wonderful administrative ability, by retrieving the family fortune. She never remarried.

Her daughters married well – respectively, John Middleton of Lee’s Legion, General Thomas Pinckney, former aid-de-camp to General Horatio Gates and participant in the Florida campaign, and Captain William Alston of General Marion’s Brigade. Numerous grandchildren played in the rooms where the British officers had lived during the occupation.

During her last years in the old mansion, Rebecca was proudly pointed out to visitors to the city. One of her great-grandchildren said at that time:

She was rather under-sized and slender, with a pale face, blue eyes, and grey hair that curled slightly under a high-crowned ruffled cap. She always wore a square white neckerchief pinned down in front, tight sleeves reaching only to the elbow, with black silk mittens on her hands and arms; a full skirt with huge pockets, and at her waist a silver chain, from which hung her pin-cushion and scissors and a peculiarly bright bunch of keys.

Undaunted, Rebecca Brewton Motte persevered until all her indebtedness was paid, and left her children a sizeable estate when she died in 1815 at her plantation. The body of this gracious patriot was buried in old St. Philip’s Church, another of the Revolutionary landmarks of the Palmetto City. A granite stone now marks the site where the British surrendered on May 12, 1781.

SOURCES

Rebecca Motte

The House of Rebecca Motte

Rebecca Motte, Ardent Patriot

The Women of the American Revolution

South Carolina Women of the American Revolution

Great historical information about our wonderful country, it is such a shame that so few American’s have a clue about what it took to become the envy of the world. Our terribly flawed education system is the main contributor to that ignorance.

Agreed