American Women Who Supported the British

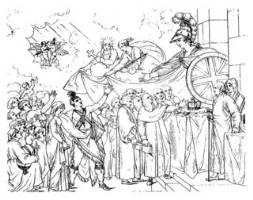

Image: Reception of the American Loyalists by Great Britain in 1783, offering solace and a promise of compensation. Engraving by H. Moses.

American colonists who remained loyal to Great Britain during and after the Revolutionary War were termed Loyalists; the Patriots called them Tories. Although Loyalists came from all social classes and occupations, a large number were businessmen and professionals, or officeholders under the crown. They also tended to be foreign born and members of the Church of England. It is estimated that about 20% of the colonial population were Tories. The Patriots enacted harsh laws against the Loyalists and confiscated many of their estates.

In 1774–75, when most colonials hoped for reconciliation with the British government, the line between Loyalist and non-Loyalist was not very sharp, but the Declaration of Independence created a sharp dividing line between supporters and opponents of American independence. By then, the Revolutionaries had gained control of virtually all territory in the thirteen colonies by violently suppressing the Loyalists, demanding that they give up their loyalty to the King.

The Loyalists were strongest in the far southern colonies – Georgia and the Carolinas – and in the Middle Atlantic colonies, especially New York and Pennsylvania. In those places particularly, the fighting became bitter civil war with raids and reprisals. The Revolutionaries deeply hated the leaders of the Loyalist armed bands, such as Thomas Browne, Edmund Fanning, and John and Walter Butler. Even before warfare began, many Loyalists were seeking refuge in British-held lands.

Outspoken supporters of the king were threatened with public humiliation (such as tarring and feathering) or physical attack. It is not known how many Loyalist civilians were harassed, but the treatment was a warning to other Loyalists not to take up arms against the Patriots. The Loyalists rarely attempted any political organization, and were often passive unless regular British army units were in the area.

Loyalists came from all walks of life. The majority were small farmers, artisans, and shopkeepers. Wealthy merchants tended to remain loyal, as did Anglican ministers, especially in Puritan New England. Most had rebel relatives. They endured extraordinary insults for their convictions, and many lost everything they owned in the colonies.

Loyalist women played key roles in the decisions of families to become Loyalist. Often, they ran the family farms and businesses when husbands had to leave suddenly to avoid capture by the Patriots. During these periods, the contributions of these women were recognized as valuable by their families, by the British authorities, and by the American Patriots.

Loyalist Wives

Whether a man did or did not renounce his allegiance to the king could dissolve ties of class, family, and friendship, and isolate their wives from former connections. A woman’s loyalty to her husband could become a political act, especially for women who were committed to men who remained loyal to Great Britain. These loyalist women faced hardships.

Although many Loyalist women followed their men into exile, others faced down rebel mobs to remain on their farms to manage the “widow’s thirds” – one-third share of their deceased husband’s estate – that they were entitled to under colonial law. And the emerging American government allowed it, so that they and their children would not become burdens on their towns.

There was pressure on Loyalist women to leave their property, even at great sacrifice. However, in leaving they lost any semblance of independence. They often required permission from local committees of vigilance. Then, they needed aid and assistance from Indian and military guides to reach husbands stationed in military forts or in refugee camps. In these forts and camps, they were only significant as spouses; they were treated as dependents and burdens.

Wives of wealthy loyalists were particularly vulnerable – their husband’s property could be confiscated because they were considered traitors. Women with their own property may have been less vulnerable to patriot pressure, because confiscation acts normally excluded women’s property from seizure. No matter their social status, however, loyalist women were part of a political minority, and lacked the support of neighbors and friends.

Many loyalist women left their communities rather than live among their enemies, but that often meant leaving home without any family possessions. Loyalists usually moved to Canada, where they found thousands of fellow loyalists. A loyalist could petition local patriot authorities for safe passage and permission to bring personal belongings into British territory. Even then, American officials limited what a woman could take, and she had to pay for the journey.

Resistance was another option for loyalist women. Most of the women who actively supported the Crown participated by aiding loyalist soldiers or by collecting information for the British. Some loyalist women hid their husbands from arrest, while others hid important papers or money from authorities.

A major concern of Loyalists throughout the war was that the British would establish themselves in an area, invite the Loyalists to join them, and then evacuate, leaving their families behind. The vast majority of the women and children left behind by the Loyalist men – soldiers and civilians – would sooner or later be forced to leave their property by cash-starved local governments, who confiscated their property and converted it to currency to finance the war.

In all territories where there was a Rebel government in power, property and land was confiscated regardless of whether a family occupied a house or not. Usually, the owner’s name was published in a newspaper, and they had until a certain time to present themselves and state their case. In almost all cases, the owners couldn’t appear, because they would be arrested and tried for high treason.

New York Loyalists

The British had been forced out of Boston between March 4th and March 17th, 1776; but they returned to New York in August to convincingly defeat the Continental army at Long Island and in doing so, captured New York City and its vicinity, where they remained until 1783.

Many tenant farmers in New York supported the king, as did many of the Dutch there and in New Jersey. The Germans in Pennsylvania tried to stay out of the Revolution, just as many Quakers did, and when that failed, they sided with the British. New York City and Long Island had a very large concentration of Loyalists, many of whom were refugees from other states.

When British General John Burgoyne began marching south with his army in 1777, the Loyalist families in upper New York and Vermont felt that the uprising of the rebels would be over soon and joined in the fighting to keep their part of the world loyal to the King. Left behind to manage the farms and families alone, when their husbands left to fight, the Loyalist women served as providers and caregivers, sometimes for very large families.

But they played another role as well, which became very important to the Loyalists. They provided shelter for escaped prisoners and Loyalist agents passing through, and food-providers for those heading north. They were aware that if they were caught, they would either go to jail or worse.

The Vermont Council of Safety recounted the various ways in which the Loyalist women aided the enemy: by providing intelligence or by feeding, housing, or supplying Loyalist or British soldiers. The Council resolved that these families be removed to within Patriot lines.

Most of the colonies adopted similar laws, but the Loyalist women were not forced to leave immediately, so they continued helping the British cause by allowing messages to get through between the Loyal Block House on Lake Champlain and General Clinton in New York City. The families stayed on until their farms were confiscated, at which time the women and children were given twenty days to leave the area or be imprisoned.

There had to be secrecy within the neighborhood. People were divided in their loyalties and it was difficult to know whom to trust. Sometimes the husbands came home during the night, but not often, and only if they were delivering messages to other agents. The whole family was sworn to secrecy, because one word by a child to another playmate could cause the family to be sent away or jailed.

A typical upstate New York family was that of Mary Swords. Her husband had served in the French and Indian War as a lieutenant, afterwards settling on a farm and Potash works in Saratoga. He was apprehended at the beginning of the war and sent to jail in Albany as a dangerous person. On the advance of Burgoyne’s army toward Albany in 1777, Rebel troops and Indians in the British service plundered the farm of all its furniture, leaving Mary only her clothing. She and her family were turned out of their homes after Burgoyne’s surrender, and forced to move within the British lines.

Middle Atlantic States

Life was no less difficult for Loyalist families in the Middle Atlantic States. In all the towns and villages throughout this area was a network of safe-houses, where Loyalists and British Soldiers on the run could find safety and a hot meal, while they made their way from Rebel prisons in the hopes of reaching New York safely.

One of the terrible worries suffered by many Loyalists was that their actions would cause punishment, harm, or worse upon their families at home. In an age when protection for a family was most often found in the father with a loaded musket, the absence of that weighed heavily on the minds of many.

Slowly at first and then by waves, the families of Loyalist soldiers came into the army. With no means of support at home, made enemies by many of their neighbors, and often having their homes confiscated from around them, these women had little choice but to join the army.

While mundane camp duties were the norm, these women’s unique knowledge of the countryside, coupled with the non-combatant status of women, allowed their use in various clandestine military roles. The British Secret Service, run through the Adjutant General’s Department, at least several times used women in their line of work.

Widows and Orphans

Whether an officer or enlisted soldier, the death of officers and soldiers deeply affected those they left behind. Widows of officers killed in action could expect a bounty of one year’s pay; they found life without their late husbands difficult in the extreme. While the problems of the officers’ widows were basically that of financial freedom, those of the other ranks was as severe as not knowing where their next meal was coming from.

As only wives of soldiers could receive rations, no provision was made for the widows and children. Some of these women left the new United States to settle in parts unknown to them – Jamaica, England, Abaco, and Bermuda – but mostly they settled in what is now Canada.

After the War

Nearing the end of the Revolutionary War, New York City was the last bastion of British fortification, and thousands from the thirteen colonies along the Eastern seaboard of North America who supported Great Britain had congregated in that city for their safety and protection.

In the late summer of 1782, those Loyalists who had been crowding into New York were aware of the terms of the treaty the British delegation to Paris would be required to accept in return for peace. They also knew that the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Lord Shelburne, had failed in his attempt to secure any guarantee of safety for those who had supported the British cause. Their lands would be confiscated, and there would be no alternative but to leave the land they had known as home.

When their cause was defeated, about 20% of the Loyalists left the U.S. to resettle in other parts of the British Empire. Many of those Loyalist families had roots going back to the first English settlements in North America. Some like Captain Gideon White were descendants of Mayflower passengers whose ancestors arrived in 1620.

The Governor of Nova Scotia made it known that those who wished to establish themselves in Nova Scotia would be most welcome, and they could continue to live there under British rule. Located on the southwestern shore of Nova Scotia, Port Roseway became a haven of refuge for over 12,000 Loyalist refugees of the American Revolution in 1783.

The Loyalists were brought to Nova Scotia by British transport vessels, the first group arriving May 4, 1783. Successive fleets followed in June and early fall of 1783 and throughout the next few years. Within a year from the arrival of the first fleet, the population of the town swelled to approximately 10,000.

The vast majority of white Loyalists (450-500,000) remained in America during and after the war, staying on although they were not recognized as citizens of the new country. Starting in the mid-1780s a small percentage of those who had left returned. Of those who left Massachusetts, virtually none of them expressed a desire to return to their native home, as the wave of anti-Toryism persisted.

Loyalists who had stayed were subjected to fines, land confiscation, and triple taxation. Any making their way back to Massachusetts between 1784 and 1789 found their reception was as hostile as ever. They found that in Massachusetts in particular, they not only encountered extreme anti-Toryism, but society was so chaotic they couldn’t re-integrate themselves into society, reclaim property, work in their profession, collect debts, or join the political culture of the state.

The Treaty of Paris required Congress to restore property confiscated from Loyalists. The heirs of William Penn, for example, and those of George Calvert in Maryland received generous settlements. In the Carolinas, where enmity between Rebels and Loyalists was especially strong, few of the latter regained their property. In New York and the Carolinas, the confiscations from Loyalists resulted in something of a social revolution as large estates were parceled out to yeoman farmers.

SOURCES

Loyalist Families

Female Ancestors

Loyalist (American Revolution)

Loyalists During the American Revolution

who fought five loyalist who attacked her home and captured all of them

I’m about to publish my book which details the most sensational crime of the American eighteenth century, instigated by its most notorious female Loyalist, Bathsheba Spooner. Her infamous Loyalist father, Timothy Ruggles, was exiled to Nova Scotia; his daughter met her end on the gallows in Worcester, July 1778.