Wife of Declaration of Independence Signer: William Hooper

Image: William Hooper

William Hooper was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1742. His early education, at the age of seven, was seven years at the Boston Latin School. When he completed these studies, he entered the sophomore class of Harvard College in 1757, at age 16, graduating in 1760 with a B.A. degree and in 1763 with a M.A. degree. Although William Hooper’s parents wanted him to enter the clergy, but much to the chagrin of his father rejected the ministry as a profession.

The next year, he further alienated his Loyalist father and isolated himself from his family by studying law under James Otis, a brilliant but radical Boston lawyer. After passing the bar exam, he decided to leave home, because Boston already had too many attorneys.

In 1764, Hooper settled in Wilmington, North Carolina, to begin the practice of law. He was warmly received by the planters and lawyers of the lower Cape Fear region and became a Circuit Court Lawyer, following the sessions of the court and traveling hundreds of miles on horseback. By June 1766, he was unanimously elected recorder of the borough.

On August 16, 1767, William Hooper married at King’s Chapel in Boston, Anne Clark of New Hanover, North Carolina, the daughter of Barbara Murray and Thomas Clark, Sr., a wealthy early settler to the region and the late sheriff of New Hanover County. The two had a son, William, in 1768, followed by a daughter, Elizabeth, in 1770 and then another son, Thomas, in 1772.

Anne was the sister of Thomas Clark, Jr., who became a colonel and brigadier general in the Continental Army. It was the fortunate affluence of the Clark family that enabled the Hoopers to survive the difficult years of the American Revolution.

Anne and William lived either in Wilmington or at his nearby estate, Finian, about 8 miles away on Masonboro Sound, rode the circuit from court to court, and built up a clientele among the wealthy planters of the lower Cape Fear region. Ambitious, he harbored political aspirations and by 1770-71 had obtained the position of deputy attorney general of North Carolina.

Hooper built a highly respected reputation in North Carolina among the wealthy farmers as well as fellow lawyers. He increased his influence by representing the colonial government in several court cases. But from the beginning, his health was precarious in the low-lying Wilmington area.

Initially Hooper supported the British government in North Carolina. The increasingly popular Hooper was appointed Deputy Attorney for the Salisbury district in 1769, and Deputy Attorney General for North Carolina in 1770.

As Deputy Attorney General of North Carolina, he sided with Royal Governor William Tryon, and worked to suppress a rebellious group known as the Regulators, an uprising that lasted from 1764 to 1771, where citizens took up arms against corrupt colonial officials.

In 1770, it was reported that the group dragged Hooper through the streets of Hillsborough during a riot. Hooper advised Governor Tryon to use as much force as was necessary to stamp out the rebels, and even accompanied the troops that defeated the rebels in the Battle of Alamance in 1771.

But Hooper’s support of the colonial government began to erode, causing problems for him due to his past support of Governor Tryon. Hooper had been labeled a Loyalist, and therefore he was not immediately accepted by the Patriots.

Hooper eventually was elected to the North Carolina General Assembly in 1773, where he became an opponent to colonial attempts to pass laws that would regulate the provincial courts. This in turn helped to sour his reputation among Loyalists.

During his time in the assembly, Hooper slowly became a supporter of the American Revolution and independence from Britain. After the governor disbanded the assembly, Hooper helped to organize a new colonial assembly. His Loyalist father was displeased and disowned his patriotic son.

William’s prophetic observation in a letter of April 26, 1774, to his friend James Iredell is often quoted as a landmark of colonial foresight at this early period. Hooper wrote:

The Colonies are striding fast to independence, and ere long will build an empire upon the ruins of Great Britain; will adopt its Constitution, purged of its impurities, and from an experience of its defects, will guard against those evils which have wasted its vigor.

This was the earliest known prediction of independence, which won for Hooper the epithet Prophet of Independence.

William Hooper became a man of prominence in the legislative body, and in 1774 was chosen as one of the delegates to the First Continental Congress. With Thomas Jefferson, he served on a committee to draft the Declaration of Independence. He was elected to the Second Continental Congress, but much of his time was split between the congress and work in North Carolina, where he was assisting in forming a new government.

Because of those duties, Hooper missed the vote approving the Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July, 1776, but arrived in time to sign it on August 2, 1776.

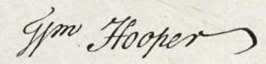

William Hooper’s Signature on the Declaration

In 1777, financial difficulties with his law practice and a desire to be near his family prompted him to resign from Congress and return to Wilmington. Hooper resumed his residence at Finian and his law practice in the newly opened courts, again riding the circuits with his friend Iredell as he had done before the Revolution. He also attended the General Assembly from 1777 until 1781 for the borough of Wilmington, serving on numerous committees.

Throughout the Revolution, Hooper was sought by the British as a traitor for signing the Declaration of Independence. They decided to educate Hooper so that all rebels would understand the consequences of their actions. In 1780, the British invaded North Carolina. Hooper moved his family from Finian into Wilmington for safety, but in January 1781, while he was away on business, Wilmington fell to the enemy, and Hooper was separated from his family.

Suffering from malaria and a badly injured arm, Hooper became a fugitive from the British, and was forced to rely on friends in Edenton for food and shelter, hiding from house to house in the Windsor and Edenton areas. The Hooper house in Wilmington was burned, and an ailing Anne Hooper and two of her children were forced to flee by wagon to Hillsborough in central North Carolina, where her brother, General Thomas Clark, found shelter for them. When the British left the Wilmington area in November 1781, Hooper returned to find that they had also shelled his plantation house at Finian.

After nearly a year of separation, Hooper was reunited with his family. On April 10, 1782, the Hoopers purchased General Francis Nash’s former home and settled in Hillsborough. He established a mini-plantation on his eight acres, with the help of 24 slaves, and built a law office on the grounds. He remained to some extent in public life as a state legislator, but never regained his early prominence.

After independence was won, Hooper returned to his career in law, but he lost favor with the public due to his political stance. He pursued a conservative path, which many disagreed with. As stipulated in the treaty ending the war, he forgave Loyalists and protected their rights, even when the majority in his jurisdiction wanted revenge. The British reneged on their obligations, which only made matters worse.

In 1787, he campaigned heavily for North Carolina to ratify the new United States Constitution. But by this time he had become quite ill. He was appointed a federal judge in 1789 and served for one year, before his bad health forced him to retire.

After five months of complications associated with his previous health problems, William Hooper died at Hillsborough on October 14, 1790, at the age of forty-eight. Anne Hooper died in August 1795. They were initially interred at the Presbyterian Churchyard in Hillsborough.

In 1894, William’s remains were sent to the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park in Greensboro. There, an imposing 19-foot-high monument, surmounted by a statue of Hooper in colonial dress and in orator’s pose, honors the patriotic services of William Hooper. The sandstone slab, with six additional words deeply incised, Signer of the Declaration of Independence, was later returned to the original Hillsborough grave site.

We seldom think about how young the founders of our country were when they pledged their lives and fortunes – and sometimes sacrificed them. Many of them died poor. William Hooper was only 35 years old when he signed the Declaration.

SOURCES

William Hooper

Hooper Archives

Wikipedia: William Hooper

William Hooper (1742-1790)

Signer of the Declaration from North Carolina