American Revolution Loyalist

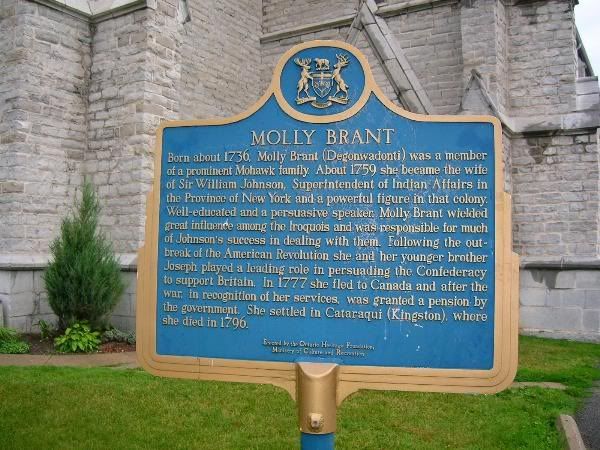

Molly Brant Plaque

Kingston Ontario

Molly Brant was an important Mohawk woman in upstate New York and Canada in the era of the American Revolution, particularly in the Mohawk Valley, the area surrounding the Mohawk River, sandwiched between the Adirondack and Catskill Mountains. Her younger brother, Joseph Brant, grew into a celebrated Mohawk statesman in his own right and rubbed shoulders with the likes of U.S. General George Washington and King George III of England.

Molly Deganwadonti was born in 1736, the daughter of Peter Tehonwaghkwangeraghkwa and his wife Margaret, both Mohawks of the Wolf clan from Canajoharie – the site of a barricaded long house village of the Mohawk tribe of the Iroquois Nation in New York. After Peter’s death, Margaret married Brant Kanagaradunkwa, a Mohawk sachem of the Turtle clan, who owned a colonial-style frame house and lived and dressed in the European style.

Although not much is known of Molly’s life at Canajoharie during the 1740s and 1750s, from her infancy through her teenage years and into her early twenties, it is likely that she lived in Nickus Brant’s house. She was well educated in the European ways of life, with her formal education likely taking place in an English mission school, as she learned to speak and write English well.

Molly Brant’s political activity began when she was 18 years old. In 1754, she accompanied a delegation of Mohawk elders to Philadelphia to discuss fraudulent land transactions. This trip may have been part of her training in the Iroquois tradition, for she was to become a clan matron.

A British officer during the French and Indian War, William Johnson dealt honestly with the Mohawk, who appreciated his mastery of their language. His victory over the French and Algonquin in 1755 at the Battle of Lake George, New York, earned him a British knighthood. Johnson was eventually appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the province of New York.

During this time, Molly met Sir William Johnson, and moved into his house, Old Fort Johnson, before the birth of their first son Peter in September 1759. Molly was about 23, while William was 44 years old. She became Johnson’s common-law wife in a traditional Mohawk ceremony. Johnson couldn’t formally marry her because Molly was considered of a lower class. The couple had nine children together, eight of whom survived.

Johnson had acquired 600,000 acres of land in the Mohawk Valley, making him one of the richest men in the colonies. He was a successful colonial trader, and adapted well to Native ways. The Mohawk called him Warraghiyagey, a man of many interests, in tribute to his irrepressible curiosity.

Molly immediately took control of the household, managing its many slaves, servants, and staff and ran Johnson’s complicated administrative tasks with his secretary and bookkeeper. The family lived first at Old Fort Johnson from 1759 to 1763, and then at Johnson Hall, near Schenectady, from 1763 to 1774.

Johnson Hall: Home of Molly Brant

The house was flanked by two fully armed stone blockhouses.

Johnson Hall was even more elegant than Fort Johnson, and it was larger. The two-story Georgian, white-frame façade was 55 feet long, with four large rooms on the ground floor, a centre hall, and a great staircase. There were two fireplaces, as many windows in the rear of the house as in the front, and a large cellar beneath the entire structure.

A contemporary visitor to Johnson Hall, an English woman, described Molly Brant: “Her features are fine and beautiful; her complexion clear and olive-tinted… She was quiet in demeanor, on occasion, and possessed of a calm dignity that bespoke a native pride and consciousness of power. She seldom imposed herself into the picture, but no one was in her presence without being aware of her.”

Molly flourished in both Mohawk and colonial British society and often mixed the wardrobes of both with great flair, looking and sounding like the leader she had become. The British were often in awe of her self-presentation, poise and persuasiveness. She was also an expert herbalist, and the large herb garden at Johnson Hall is testimony to her interest in what was a lifelong pursuit.

Sir William died at the outbreak of hostilities in July 1774, exhausted by the demands of office and by a lingering war wound that had left a musket ball permanently lodged in his leg.

As a widow, Molly filled the vacuum created by his death and became the vital political link between the British and the Iroquois Confederacy, and did so while feeding, educating, and protecting her eight children from the savagery of frontier war.

Molly Brant returned to Canajoharie with eight children and four slaves. She had a large house and became a trader. She helped her brother operate a trading store, and supplied Loyalists forced to flee to the forests with food and ammunition.

Disharmony in the Thirteen American Colonies had been threatening the peace for some time. Support for the rebellion by the population was far from unanimous: about one third supported it, one third was indifferent, and the final third remained loyal to the British crown. Nonetheless, an organized revolutionary movement developed in the Mohawk Valley in May 1775.

At the start of the Revolutionary War, Molly did her best to keep the Mohawks loyal to the British. She gathered information and passed it to the British. She provided food and ammunition to the local Loyalists, and hid them in her house. Under increasing pressure from colonial militia, by 1776, all the Loyalist leaders and her brother Joseph and his family had left for Canada.

The advancing patriots ultimately left Molly no choice but to flee, and she left the Mohawk Valley with her family and fled to Fort Niagara, Canada, in November 1777. She left so quickly that she had to leave most of her belongings behind. The Oneidas (the only Iroquois nation allied with the colonists) and the Americans took revenge by pillaging her home in Canajoharie.

In the spring, she was given her own house which she regarded as unsuitable. In the summer of 1778 she traveled to New York to visit several villages there, but returned to Fort Niagara in November. The British built a house for her on Carleton Island – in the St. Lawrence River in upstate New York.

Now, more than ever, Molly was expected to use her influence over the Mohawk warriors. She used the colonial administration to increase her own political power and to promote the interests of her people, and they used her as an instrument of political control. Throughout the war, Molly continued to use her influence to steady the warriors, bolster their morale, and strengthen their loyalty to the King.

As the war continued, native, loyalist, and patriot settlements were attacked and burned. Thousands of destitute Iroquois made their way to Fort Niagara, suffering from starvation and illness. Compounding the situation, the winter of 1779-1780 was one of the most severe on record.

Support for the American cause from France, Spain, and the Netherlands, and underestimation by the British of the Americans’ determination to gain independence, ultimately decided the outcome of the war. The surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781 ended the war and forced England to recognize the independence of the Thirteen Colonies.

After the war, the British to whom Molly and the natives had been so loyal, reneged on their promise to address native grievances in the Treaty of Paris in 1783. To them she was an indispensable native leader and pacifier; to her embittered people she had become a pariah. The Iroquois lost their ancestral homeland, but were rewarded for their loyalty with Canadian land grants and financial compensation.

In November 1783, Molly Brant decided that the site of an old French fort at Cataraqui, near Kingston, Ontario, would be a good place to settle, for herself and the other Loyalists. Arrangements were made for the movement of troops, equipment, and even buildings from Carleton Island, now located on the American side of the new border.

Old French Fort At Cataraqui

The government built a large house for Molly that was described as being 40 by 30 feet with one and one-half stories, and a house for her brother Joseph was built next door. She was also granted a pension of 100 pounds per year and a supplement of twelve hundred pounds for property losses in the American Revolution.

Historical records and recent writings present Molly Brant as a strong individual who retained her native heritage throughout her life. She insisted on speaking Mohawk, she dressed in Mohawk style throughout her life, and she encouraged her children to do the same.

In 1785, Molly traveled to Schenectady in the Mohawk Valley, apparently to sign legal documents. It is reported that the Americans wanted her and her family to return, and went so far as to offer financial compensation. The response was that she rejected the offer “with the utmost contempt.”

On April 16, 1796, Molly Brant died at the age of 60. She was laid to rest in the burial ground of St. George’s Church. A plaque was erected in her memory; another is on an interior wall of St. George’s Cathedral. On Molly Brant Celebration Day, 25 August 1996, a plaque and a sculpture were unveiled on the Rideaucrest grounds.

SOURCES

Mary Brant

Molly Brant

Mary (Molly) Brant

The Rideau Warriors

Who Was Molly Brant?

Mary (Molly) Brant Biography

Seventh of Twelve: Molly Brant

Please respect Molly Brant by referring to her by both names or preferably by her Tribal name—Why is it William Johnson but Molly? That’s not appropriate thank you

I am confused of the to names that she has cant figure out witch one is her real name

Molly Brant (c. 1736 – April 16, 1796), also known as Mary Brant, Konwatsi’tsiaienni, and Degonwadonti

As an indigenous person she held a few names. I hope that helps. In general through history, women tend to have a few names. My best guess is these are based on familiarity with the person.

Odd that this post has a painting of the Lily of the Mohawks: Tekawitha

Molly Brant is my 8th great grandmother. My sister recently traced back to her on our paternal grandmother’s side of the family. So interesting to find her.