The Year: 1755

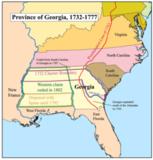

Between 1735 and 1750, Georgia was unique among Britain’s American colonies, because it was the only one to attempt to prohibit black slavery as a matter of public policy. The decision to ban slavery was made by the founders of Georgia, the Trustees.

Slavery Banned in Georgia

General James Oglethorpe, the earl of Egmont, and the other Trustees were not opposed to the enslavement of Africans as a matter of principle. They banned slavery in Georgia because it was inconsistent with their social and economic intentions. Given the Spanish presence in Florida, slavery also seemed certain to threaten the military security of the colony. Spain offered freedom in exchange for military service, so any slaves brought to Georgia could be expected to help the Spanish in their efforts to destroy the still-fragile English colony.

The Trustees wished to guarantee the early settlers a comfortable living rather than the prospect of the enormous personal wealth associated with the plantation economies elsewhere in British America. They would obtain this living by working for themselves rather than being dependent upon the work of others. The Trustees believed that the silk and other Mediterranean-type commodities they envisaged for Georgia did not require the employment of enslaved Africans but could be easily produced by Europeans.

Initially the Trustees believed the settlers would follow their wishes and not use enslaved workers. Oglethorpe realized, however, that many settlers were reluctant to work. Some settlers began to grumble that they would never make money unless they were allowed to employ enslaved Africans. Many South Carolinians, who wanted to expand their planting interests into Georgia, encouraged this line of thinking.

Oglethorpe soon persuaded the other Trustees that the ban on slavery had to be backed by the authority of the British government. The influential Trustees easily persuaded the House of Commons that their intentions for Georgia, and the colony’s very survival in the face of the Spanish threat, depended upon the exclusion of enslaved Africans.

In 1735, two years after the first settlers arrived, the House of Commons passed legislation prohibiting slavery in Georgia.

Slavery Demanded

Georgians’ campaign to overturn the parliamentary ban on slavery was soon under way, and grew in intensity during the late 1730s. Its two most important leaders were a Lowland Scot named Patrick Tailfer and Thomas Stephens, the son of William Stephens, the Trustees’ secretary in Georgia. They and their band of supporters bombarded the Trustees with letters and petitions demanding that slavery be permitted in Georgia.

The crux of their argument was that the Trustees’ economic design for Georgia was simply impractical. They insisted that it would be impossible for settlers to prosper without enslaved workers. West Africans, they argued, were far more able than Europeans to cope with the climatic conditions found in the South.

As the growing wealth of South Carolina’s rice economy demonstrated, slaves were far more profitable than any other form of labor available to the colonists. Tailfer and Stephens wanted to recreate the slave-based plantation economy of South Carolina in the Georgia Lowcountry.

Before the late 1730s, the Trustees were not under any serious pressure to lift the ban. All this began to change when Thomas Stephens realized that financial pressure could be brought to bear on them. Because the Trustees depended upon the British House of Commons to finance the continuing settlement and defense of Georgia, Stephens tried to persuade the House to make its financial support conditional upon the introduction of slavery.

He spent time in London lobbying members of Parliament and trying to secure a broad base of public support for his arguments. Thanks to the political influence of the Trustees, his efforts bore little fruit. As long as Spain remained a threat, the British Parliament was willing to invest money into the Georgia project.

The situation changed dramatically in 1742, when Oglethorpe defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Bloody Marsh and returned to England. In Oglethorpe’s absence a growing number of settlers became more willing to ignore the ban on slavery.

By the mid-1740s the Trustees realized that excluding slavery was rapidly becoming a lost cause. Oglethorpe had virtually lost interest in Georgia by this time. In the absence of strong leadership, there was little to prevent the Georgia settlers from illicitly importing slaves primarily through Augusta.

The Trustees, bowing to the inevitable, agreed that the ban on slavery be overturned, but only after they had consulted their officials in Georgia about the conditions under which slavery would be permitted. In opposition to South Carolina’s slave code, the Trustees wished to ensure a smaller ratio of blacks to whites in Georgia. These consultations were completed by 1750.

The Trustees asked the House of Commons to replace the Act of 1735 with one that would permit slavery in Georgia as of January 1, 1751. The legislation they recommended was adopted. The Trustees’ desire to exert an influence on the pattern of slavery and race relations in Georgia, even after their Royal Charter expired in 1752, proved very short-lived.

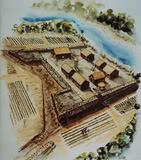

Rice Culture on the Ogeechee

Near Savannah, Georgia

A. R. Waud’s sketch depicts slaves working in the rice fields. The vignette illustrates the various stages in rice cultivation, including ditching, flooding, reaping, and threshing. The aim of the planter was to harvest the rice before the arrival of rice-eating bobolinks, or rice birds.

Slavery Permitted

The lifting of the ban opened the way for Carolina planters to fulfill the dream of expanding their slave-based rice economy into the Georgia Lowcountry. The planters and their slaves flooded into Georgia and soon dominated the colony’s government.

In 1755, they replaced the slave code agreed to by the Trustees with one that was virtually identical to South Carolina’s. This code was amended in 1765 and again in 1770.

The South Carolina migrants enjoyed a significant wealth advantage over the original settlers of Georgia. They quickly established socioeconomic structures and relationships that were nearly identical to those they had known in their own colony. Within twenty years some sixty planters who owned roughly half the colony’s rapidly increasing slave population dominated the apex of Lowcountry Georgia’s rice economy.

Between 1750 and 1775, Georgia’s enslaved population grew in size from less than 500 to approximately 18,000 people. Beginning in the mid-1760s, Georgia began to import slaves directly from Africa – mainly from Angola, Sierra Leone, and the Gambia. Most were given physically demanding work in the rice fields, although some found employment in Savannah’s expanding urban economy.

Slaves had no legal right to private lives, and they struggled against daunting odds to establish some degree of autonomy for themselves. With varying degrees of success, they tried to recreate the patterns of family and religious life they had known in Africa.

Revolutionary Era Slavery

The circumstances of slavery in the Georgia Lowcountry precluded the possibility of organized rebellion. Yet enslaved people resisted their owners and asserted their humanity in ways that included running away as well as acts of verbal and physical violence. The American Revolution (1775-83) would offer them the best prospect of freedom.

By the mid-1750s, almost every white person in the Georgia Lowcountry at that time believed that the institution of slavery was essential to his or her economic prosperity. During the remainder of the colonial period, no white Georgian voices were raised to challenge that assumption.

The American Revolution probably affected the lives of nearly all slaves in coastal Georgia. Some were killed in war; many more fled to try to find a better life for themselves. Only a small fraction of those actually found that better life, either in freedom or in exile far from the Georgia plantations.

Antebellum Slavery

For almost the entire eighteenth century Georgia’s plantation economy was concentrated on the production of rice, a crop that could be commercially cultivated only in the Lowcountry. During the Revolution, planters began to cultivate cotton for domestic use.

After the war the explosive growth of the textile industry promised to turn cotton into a potentially lucrative staple crop – if only efficient methods of cleaning the seeds from the cotton fibers could be developed. By the 1790s, entrepreneurs were perfecting new mechanized cotton gins, the most famous of which was invented by Eli Whitney on a Savannah River plantation in 1793. This technological advance presented Georgia planters with a staple crop that could be grown over much of the state.

As was the case for rice production, cotton planters relied upon the labor power of enslaved Africans and African Americans. Accordingly, the slave population of Georgia increased dramatically during the early decades of the nineteenth century. In 1790, just before the explosion in cotton production, some 29,264 slaves resided in the state.

In 1793, the Georgia Assembly passed a law prohibiting the importation of slaves. The law did not go into effect until 1798, when the state constitution also went into effect, but the measure was widely ignored by planters, who urgently sought to increase their enslaved workforce.

Over the antebellum era, whites continued to employ violence against the slave population, but increasingly they justified their mastery in moral terms. As early as 1790, Georgia congressman James Jackson claimed that slavery benefited both whites and African Americans.

The expanding presence of evangelical Christian churches in the early nineteenth century provided Georgia slaveholders with religious justifications for human bondage. White efforts to Christianize the slave quarters enabled masters to frame their power in moral terms. They viewed the Christian slave mission as evidence of their own good intentions.

By 1800, the slave population in Georgia had more than doubled, to 59,699; by 1810 the number of slaves had grown to 105,218. In 1820, 149,656; in 1840 the slave population had increased to 280,944.

Low Country Slavery

Throughout the antebellum era some 30,000 Georgia slaves resided in the Lowcountry, where they enjoyed a relatively high degree of autonomy from white supervision. Most white planters avoided the unhealthy Lowcountry plantation environment, leaving large slave populations under the supervision of a small group of white overseers.

Slaves were assigned daily tasks and were permitted to leave the fields when their tasks had been completed. Lowcountry slaves enjoyed a far greater degree of control over their time than was the case across the rest of the state, where slaves worked in gangs under direct white supervision. The white cultural presence in the Lowcountry was sufficiently small for slaves to retain significant traces of African linguistic and spiritual traditions.

In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, some 462,198 slaves constituted 44 percent of the state’s total population. By the end of the antebellum era, Georgia had more slaves and slaveholders than any state in the Lower South and was second only to Virginia in the South as a whole.

In the wake of war, white and black Georgia residents articulated opposite views about emancipation. The former slaveholders bemoaned the demise of their plantation economy, while the freed slaves rejoiced that their bondage had finally ended.

SOURCES

Slavery in Georgia

Slavery in Colonial Georgia

Slavery in Antebellum Georgia

Slavery in Revolutionary Georgia

You stated slaves enjoyed autonomy from whites…Apparently you must be white because MY ANCESTORS did NOT enjoy any part of slavery. It amazes me of the things people will say who was not affected by slavery…whose family isnt suffering from generational issues due to slavery. You had the audacity to use the word enjoy and down play the torture my family and others went through.