English Women and African Slaves

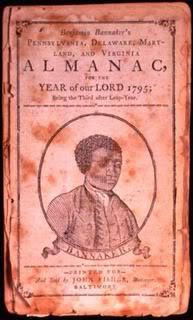

Banneker’s 1795 Almanac

In 1690, after working for seven years on a tobacco plantation in Maryland, Molly earned her freedom, and bought a 120-acre farm ten miles from Baltimore. In 1692, she bought two slaves from a ship in the Chesapeake Bay. One of the slaves was a man named Banneka, the son of an African chieftain. Banneka’s intelligence and dignity deeply impressed Mary Welsh.

In England, during the 17th century, people who were convicted of crimes were sometimes shipped to the American colonies to work on plantations. In 1683, Molly Welsh, an English dairy maid, was found guilty of stealing milk from a farmer. In fact, she had accidentally knocked over a pail of milk, but the mistake was costly. Molly was indentured to a Maryland tobacco farmer to pay for her crime.

English/African Wedding

Within three years, Molly freed Banneka. In spite of strict Maryland laws against interracial marriages, Molly and Banneka married and had a daughter, Mary, one of four daughters they had between 1710 and 1720. (Their name was later changed to Banneker.) At least 256 white women were prosecuted in Maryland for marrying black men during the colonial period. Some had a number of children, indicating long-standing relationships.

When Mary Banneker fell in love with a slave named Robert from Guinea, West Africa, Molly and Banneka bought his freedom so the young couple could marry. Having no surname, Robert took his wife’s family name as his own. Benjamin Banneker was born in 1731, the first of the four children they would have.

Backwoods Education

His grandmother, Molly Welsh Banneker, was his first teacher. She taught him to read and write by using a Bible she had imported from England. Benjamin’s mind was sharp, and he soon learned all that Molly had to teach, so she sent him to a one-room integrated school near her farm. It was open only during the winter months, when the children didn’t have to work on their parents’ farms. There, he received eight years of schooling from a Quaker teacher, the only formal education he ever had.

Mathematician

As he grew older, Benjamin had to work full time on his father’s farm, but he continued to educate himself for the rest of his life. Few books were available at the time – Benjamin couldn’t afford a book of his own until he was thirty-two years old – but he managed to borrow books and teach himself literature, history, and mathematics. He was so good at mathematics that visitors came from far away with practical problems or brain-teasing puzzles for him to solve.

At age twenty-two, Benjamin built a striking clock without ever having seen one. First, he studied the workings of a small watch, then used a pocket knife to carve each part of his clock from wood he had collected and carefully seasoned. He used metal parts only where they were absolutely needed. It was the first clock of its kind in the Maryland region.

Benjamin enjoyed the mathematical challenge of calculating the proper ratio of the many gears, wheels, and other parts, then fitting them together to move in harmony. His clock operated for more than forty years, striking the hours of six and twelve. Visitors came from miles around to see the amazing achievement of this self-taught man.

Tobacco Farmer

Benjamin inherited the family tobacco farm after his parents died. Still a young man, he mostly worked on the farm growing tobacco and some other crops by himself. For the next 35 years, he performed watch and clock repairs, and successfully farmed tobacco with sophisticated irrigation techniques.

In the decades before the Revolutionary War, it was widely believed that black people were incapable of intellectual achievement. Slavery and racial discrimination were justified by the argument that black people were no more capable of learning than were animals.

Then along came a man who challenged those assumptions, forcing Thomas Jefferson and others to question their belief in black inferiority. That man’s name was Benjamin Banneker, who went on to become a renowned astronomer and mathematician, and is credited with being America’s first black scientist.

Astronomer

In 1787, a friendly Quaker neighbor named George Ellicott lent Benjamin a telescope, some other instruments, and several books on astronomy. From that moment on, the study of astronomy dominated his life. He often spent entire nights studying the stars, after working all day on the farm.

The following year, he predicted his first astronomical event – a solar eclipse. Eventually, the Ellicott family bought part of the Banneker farm. They agreed to pay Benjamin enough money each year to live on, and thus enabled him to spend the last sixteen years of his life studying astronomy full time.

Urban Planner

But Benjamin’s work was suddenly interrupted by a request from neighbor, George Ellicott, to help survey a ten-square-mile area known as the Federal Territory – now Washington, DC. Congress had decided to build a new national capital there, and one of George Ellicott’s cousins, Major Andrew Ellicott, was appointed by President George Washington to head the survey.

So it was that Benjamin Banneker, at age sixty, was hired by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, to help lay out the capital. Banneker spent several months making and recording astronomical observations, maintaining the field astronomical clock, and compiling other data required by Ellicott.

A notice first printed in the Georgetown Weekly Ledger and later copied in other newspapers stated that Ellicott was “attended by Benjamin Banneker, an Ethiopian, whose abilities, as a surveyor, and an astronomer, clearly prove that Mr. Jefferson’s concluding that race of men were void of mental endowments, was without foundation.”

Author/Publisher

His work with Ellicott made Benjamin more interested than ever in astronomy, and when he returned home, he spent countless nighttime hours at his telescope. He built a work cabin with a skylight in it in order to study the stars at night, and started compiling information tables for his annual almanacs that were published between 1792 and 1797.

Famed as a recluse, he kept late hours in his laboratory and slept by day. He also involved himself in antiwar and antislavery movements by writing pamphlets and essays. Suffering ill health, he leased his land to tenant farmers and later sold off parcels, maintaining only enough money to finance his scientific experiments.

And on many nights, instead of using the telescope, the old man wrapped himself in a blanket and lay in a field watching the stars until dawn. Benjamin Banneker – author, scientist, mathematician, farmer, astronomer, publisher, and urban planner – continued to study the heavens and record his calculations for the rest of his life.

He remained a bachelor, and died in poverty at his farm on October 9, 1806. As his body was being interred, his house caught fire and burned to the ground. His books and possessions, including his prized wooden clock, were consumed by flames.

But, if not for Grandmother Molly Welsh Banneker, none of this would have happened.

SOURCES

Benjamin Banneker

Benjamin Banneker Biography