South Carolina Indian Tribes

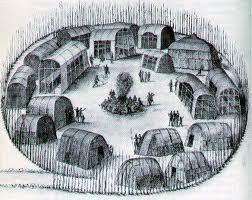

Image: Carolina Indian Village

Depicted in a drawing by John White

The cutaways in the drawing were done in order to show the interior design of the structures.

For thousands of years before Europeans arrived in present-day South Carolina, the area was occupied by Native Americans – at least 29 distinct tribes. The Catawba, Cherokee, Chicora, Edisto, Pee Dee, and Santee tribes are all still present in South Carolina. The many places in South Carolina that bear the names of tribes attest to the important role Indians played in the state’s history.

Sadly, the Indian population in South Carolina and throughout the United States greatly declined after the arrival of Europeans. Tribes were weakened by European diseases, such as smallpox, for which they had no immunity. Epidemics killed vast numbers of Indians, reducing some southeastern tribes by as much as two-thirds. Populations declined even further due to conflicts with the settlers over trade practices and land.

The Catawba

The Catawba lived in villages of circular, bark-covered houses, and temple structures were used for public gatherings and religious ceremonies. Agriculture, for which men and women both shared responsibility, provided at least two crops each year, and was heavily supplemented by hunting and fishing.

Catawba warriors had a fearsome reputation and an appearance to match: ponytail hairstyle with a distinctive war paint pattern of one eye in a black circle, the other in a white circle, and remainder of the face painted black.

A proud people and a dangerous enemy, the Catawba immediately attached themselves to the interests of the English colonists after the beginning of settlement in the Carolinas during the 1660s. They fought other Native Americans for the British and protected the Carolina colonies from encroachment by the French and Spanish.

In 1711-13, the Catawba assisted the Whites in their wars with the Tuscarora, and though they participated in the Yamassee uprising in 1715, peace was quickly made, and the Catawba remained faithful friends of the colonists ever after. By 1720, the Catawba had started to adopt many of the ways of English colonists, but were losing their own culture in the process.

Despite their incorporation of other tribes, the Catawba population was in a precipitous decline. Only 1,400 were left in 1728 after 70 years of warfare, whiskey, and disease. A terrible blow came in 1738 when a severe smallpox epidemic killed over half of them, and in 1759 the same disease destroyed nearly half of them.

A peace treaty with the Ohio Wyandot (French allies) in 1733 brought some relief, but despite all attempts by the British government and protests by southern governors, the protracted war with the Iroquois League continued until 1752. By then, the Catawba could only field 120 warriors from a population of 700.

In 1758, the Catawba abandoned their last towns in North Carolina and now lived entirely within South Carolina. Through the treaty of Pine Hill (1760) and Augusta (1763), a fifteen-square-mile reservation was established for them along the Catawba River near the North/South Carolina border.

From the beginning, the Catawba reservation suffered from encroachment by white colonists. Between 1761 and 1765, many settlers simply ignored the boundaries and moved in. A Catawba protest to South Carolina in 1763 was answered with a promise to evict the trespassers, but nothing was ever done.

The murder of the last important Catawba chief Haigler by a Shawnee war party in 1763 is generally regarded as the end of Catawba power. From that time on, the Catawba sank into relative insignificance. They sided with the colonists during the Revolutionary War and served as scouts, but that was their last important contribution.

With the South Carolina government unwilling to move against its white citizens, the Catawba land base continued to shrink. By 1826 virtually all of the reservation had been either sold or leased to whites. Crammed into the last square mile, 110 Catawba lived in poverty.

In 1840, the Catawba sold all of their land to the State of South Carolina, which agreed to obtain new territory for them in North Carolina. The latter state refused to part with any land for that purpose, however, and most of the Catawba who had gone north of the state line were forced to return.

Ultimately a reservation of 800 acres was set aside for them in South Carolina, and the main body has lived there ever since. For the most part, they remained very traditional about religion, but by 1883, Mormon missionaries were able to convert almost all of the Catawba, and most of them still belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

The Cherokee

The Cherokee are the largest tribe in the United States. They have also suffered some of the greatest losses in the history of our country. At one time, Cherokee Country stretched from the Piedmont of South Carolina into the Appalachian Mountains of Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Continuous contact between the Cherokee and the Whites began when traders from the Virginia colony began to work their way into the Appalachian Mountains. In 1670, it is estimated that the Cherokee population was around 50,000. Disease brought by European settlers killed nearly half the population.

In 1730, Sir Alexander Curving staged a personal embassy to the Cherokee, and afterward took seven of the Indians to England with him. In 1738, a smallpox epidemic decreased their numbers by nearly 50 percent.

Their relations with the Whites were upon the whole friendly until 1759, when the natives refused to turn over two of their leading chiefs to the Governor of South Carolina for execution, because they had killed a White man. The governor also asked also to have 24 other chiefs sent to him, merely on suspicion that they entertained hostile intentions.

War followed, and on August 8, 1760, the Indians captured Fort Loudon, a post in the heart of their country, after defeating an army that came to relieve it. The following year, however, the Cherokee were defeated on June 10, by a larger force under Colonel James Grant, who left many Middle Cherokee settlements in ashes, and compelled the tribe to make peace.

On the outbreak of the American Revolution, the Cherokee sided with the British, and hostilities continued until 1794. Parties of Cherokee pushed down the Tennessee River and formed new settlements near the present Tennessee-Alabama boundary.

Shortly after 1800, missionary work was begun among the Cherokee, and in 1820 they adopted a regular form of government that was modeled on that of the United States. In the meantime, large numbers of them – weary of the encroachments of the Whites – had crossed the Mississippi and settled in the territory now included in the State of Arkansas.

In 1821, Sequoya, son of a mixed-blood Cherokee woman, created the Cherokee language, a syllabary – a list of individual letters and syllables – and Cherokee of all ages began learning it with such zeal that in a few months many of them were able to read and write with it. In 1822, Sequoya went west to teach his alphabet to the Indians of the western division, and he remained there permanently.

The pressure from the Whites was soon increased by the discovery of gold in their territory in Georgia. After a few years of fruitless struggle, the Cherokee Nation bowed to the inevitable. By the Treaty of New Echota, December 29, 1835, they sold the last of their land and agreed to move to lands set apart for them in the northeastern part of the present Oklahoma.

The greater part of the tribe made the trip by walking, on horseback, or in wagons across the Mississippi during the winter of 1838-39. They suffered great hardships and lost nearly one-fourth of their number on the long trek that has become known as The Trail of Tears.

Several hundred Cherokee escaped to the mountains where they lived as refugees. In 1842, through the efforts of an influential trader named William H. Thomas, the Eastern Cherokee received permission to remain on the Qualla Reservation, lands set apart for them in western North Carolina, where their descendants still live.

The Chicora

The Chicora were traditionally a coastal Native American tribe living near Pawley’s Island, South Carolina. They grew corn, tobacco, and beans in their gardens and domesticated animals like deer and chickens. Because of their location, the Chicora may have been some of the first Native Americans to see the Spanish explorers arrive in the 1520s.

A peaceful tribe, the Chicora traded gifts with the Spanish, but the Spanish explorers to the New World had few good intentions. Many Chicora were taken from their land as slaves. D’Allyon, one of the earliest Spanish explorers of America, travelled to Spain with Francisco Chicora, a member of the Chicora tribe. There, Francisco learned Spanish and told the Spanish royalty about the beauty of his tribal lands.

The history of the Chicora people shares much in common with the history of other tribes in South Carolina. They often suffered from discrimination, and were forced to attend separate schools, but throughout their struggle they have kept a bond with their Native American roots. Members of this tribe still live near the South Carolina coast, and are represented by the Chicora-Siouan Indian Nation near Andrews, South Carolina, and the Chicora-Waccamaw near Conway.

The Edisto

The Edisto Native Americans are comprised of two distinct groups, the Kusso and the Natchez. Shortly after South Carolina became a colony in 1670, the Kusso faced a series of conflicts with the white settlers. Due to fighting and European diseases, their population declined and they lost land to the settlers.

The Natchez originally lived near present-day Louisiana, but were driven out of their traditional homeland by French colonists. In 1747, a group of Natchez sought refuge in the Edisto area. Mixing tribal traditions and cultures was not uncommon in South Carolina tribes. These combined tribes have remained in the same area of South Carolina since the mid-1700s, calling themselves the Kusso-Natchez.

Their homes were rectangular longhouses that were made of saplings lashed together and coated on the outside with mud. Villages consisted of individual homes and usually a council house for town meetings.

Like most southeastern tribes, the Edisto had a complex belief system that stressed order. Their deities were part of the natural world, with the Sun being the most important. In addition to rites of passage and of purification for individuals, the Edisto held large communal ceremonies to mark the seasons and the yearly food cycle.

The Green Corn Ceremony was the most important yearly ritual. It took place in late summer when the corn crop had ripened. In preparation, homes were cleaned, all food from the previous year was disposed of, and all fires were extinguished. The ceremony began with two days of ritual fasting by priests and distinguished men in the center of the village.

On the third day, a new fire was kindled and the head priest gave a sermon to the entire village. Then preparations for a great feast were made, which was consumed on the fourth day, followed by singing and dancing. The ceremony was concluded when all members of the tribe painted their bodies with white clay, and then immersed themselves in water. This ceremony was thought to purify the village and prepare them for the year to come.

Edisto Island is named for its indigenous inhabitants, who were there for thousands of years before the Spanish came in the 1500s, and the English settled there in 1670. In the early 1700s, the Edisto gradually disappeared because of domination by the colonial culture, European borne diseases, struggles with other Native American tribes. and racial intermingling with black slaves and white settlers.

During the 1970s, the Kusso-Natchez tribe took the name Edisto, in honor of the river that was central to the lives of their ancestors. Edisto Indian communities can be found near the river at Four Hole Swamp, Creeltown, Summerville, Walterboro, and Ridgeville.

The Pee Dee

The Pee Dee were some of the first native people the Europeans met while exploring the Americas. Spanish explorer D’Allyon made contact with the Pee Dee in 1521. Prior to the Spanish explorers, these natives lived along the Pee Dee River from Winyah Bay (near Georgetown, SC) to the Town Creek area of North Carolina.

They raised crops for food and used the river as a trade route with other tribes. A unique tradition of the early Pee Dee was the creation of sacred burial mounds. Some of these mounds can still be found along the Pee Dee River.

The Pee Dee welcomed the English colonists when they began arriving in Charleston in about 1670. Diseases brought by the Europeans killed great numbers of the Pee Dee, yet they traded deer skins and formed alliances with the new colonists. During the Revolutionary War, the Pee Dee helped the colonists fight for independence from Britain.

Most members of the Pee Dee Indian Nation now live near the South Carolina towns of Cheraw and McColl. They continue to show a dedication to their land and the people near it. During Hurricanes Hugo and Andrew, the Pee Dee helped people with food and supplies.

In 1711, South Carolina’s English colonists enlisted the Pee Dee to fight in the Tuscarora War, and they fought alongside the colonists in the Yemassee War of 1715-1716, after which the defeated Yemassee returned to Spanish Florida. When settlers began appearing in what is now Marlboro, Marion, and Dillon Counties of South Carolina around 1730s , they were able to live with the Pee Dee with very little trouble.

Archaeologists and historians say the Pee Dee became extinct by 1808, but the oral stories passed down by the tribe’s elders tell a very different story. Between 1730 and 1800, all of the smaller tribes like the Pee Dee were almost destroyed by disease and attacks by larger tribes, and by white farmers who wanted their farmland. The Pee Dee had no defense under the law, because South Carolina had already changed their status from Indian to Mulatto, Croatan, or free persons of color.

From the late 1790s through the Indian removal acts of the 1830s, the Pee Dee and other small bands were partially assimilated into the white man’s way of life. They abandoned the round type of dwelling, and built log cabins on the land that was available to them.

From the early 1800s until the Civil War of 1861-1865, the descendants of the Original Pee Dee had become small family clans that lived on the rivers. Some were sharecroppers for white farmers who were the descendants of the settlers who the Pee Dee had helped to defeat the Red Coats. Some Pee Dee fought for the South in the Civil War, and there are many tribal members who trace their Indian heritage back to those Soldiers.

The Santee

The Santee tribe is one of the most unique in South Carolina because of their limited population. From historical records, it is believed that the Santee tribe numbered around one thousand living on middle Santee River in the year 1600. Like most Native Americans in South Carolina, the Santee have a history of trading with early colonists from Europe. Due to disease and other factors, their population dropped to under a hundred in the early 1700s.

The Santee had two villages with a total of 43 warriors in 1715, and were then settled seventy miles north of Charleston. While friendly to white people, the Santee were at war with other coastal tribes. Also in 1715, they sided with the Yamassee against the British, and were attacked and reduced by the Creek, who were allies of the British.

South Carolina colonial documents indicate that the Santee and the Congaree were cut off by the Itwan and the Cossabo, coastal tribes who were fighting for the English, and the Santee prisoners were sold as slaves in the West Indies in 1716. Those who escaped were probably incorporated with the Catawba.

The Santee had elaborate burial rituals. They buried chiefs, shamans, and warriors on earthen mounds, built low or high according to the rank of the deceased, with ridge roofs supported by poles over the graves to shelter them from the weather. Relatives hung offerings such as rattles and feathers on the poles. The ground around the platform was kept carefully swept, and all the dead man’s belongings were placed nearby. Common people were buried by wrapping their bodies in bark and setting them upon platforms.

The closest relative of the deceased painted their face black and kept a vigil at the grave for several days. As soon as the flesh had softened, it was stripped from the bones and burned, the bones were cleaned, and the skull wrapped separately in a cloth woven of opossum hair. The bones were then put into a box, from which they were taken out annually to be again cleaned and oiled. In this way, some families had in their possession the bones of their ancestors for several generations.

At places where a warrior was killed, the Santee made markers of stones or sticks. Each time a Santee passed by, they were expected to add a stone or stick in remembrance of the fallen warrior.

Today, the Santee are trying to preserve their heritage through historical and archaeological research. It is estimated that there are fewer than 400 descendants of the Santee Tribe in the state.

South Carolina once revered its native population. Governor James Glen wrote:

The concerns of this country are so closely connected and interwoven with Indian affairs, and not only a great branch of our trade, but even the safety of this Province, do so much depend upon our continuing in friendship with the Indians, that I thought it highly necessary to gain all the knowledge I could of them.

–A Description of the Province of South Carolina, 1763

SOURCES

Catawba History

South Carolina Indian Tribes