Abenaki and Pennacook

Native American Territories

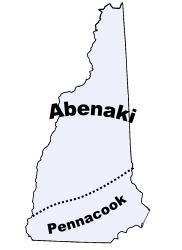

The native peoples who lived in northern New England – whose canoes cut the waters of the Connecticut, the St. Lawrence, Massachusetts Bay, and Cape Cod Sound – were called by many names, but the most common name is Abenaki, or People of the Dawn. The Abenaki occupied the greatest part of what would become New Hampshire, while a smaller tribe called the Pennacook lived in the southern part of the state.

The Eastern Abenaki were concentrated in Maine east of New Hampshire’s White Mountains, while the Western Abenaki lived west of the mountains across Vermont and New Hampshire to the eastern shores of Lake Champlain. The southern boundaries of the Abenaki homeland were near the present northern border of Massachusetts excluding the Pennacook country along the Merrimack River of southern New Hampshire.

Culture

Around 3,000 years ago, the Abenaki of New Hampshire made a great change in their life style. Although they still hunted deer, moose, and bear, they also added the practice of planting and tending the four sacred plants – corn, beans, squash, and tobacco. According to Abenaki legend, the corn was brought to them from the southwest in the eye of the crow – thus, they never killed the crows who came to raid their fields, but merely scared them away.

The practice of agriculture brought great changes to the lives of the New Hampshire Abenaki. Unlike their cousins to the north, where the growing season was too short to ripen corn to a hard stage that would keep through the winter, the New Hampshire Abenaki could store some of their crops in underground pits. Because they had stored food, they didn’t need to hunt as much and could spend their winters in villages. They also had more time for trapping animals like beavers.

Land was not owned, but used according to custom, season, and need. The Abenaki set up villages along rivers and lakes where they had access to water and could hunt, farm, and fish using traps called weirs. Favorite fishing spots were near waterfalls along the Merrimack, Connecticut, Saco, and Androseoggin Rivers. Places like Amoskeag Falls in Manchester drew thousands of people for the yearly spawning of shad, salmon, and alewife.

For most of the year, the Abenaki lived in scattered bands of extended families, each of which occupied separate hunting territories inherited through the father. Unlike the Iroquois, the Abenaki were patrilineal. In spring and summer, bands would gather at fixed locations near rivers, or the seacoast, for planting and fishing. These summer villages were sometimes fortified, depending on the warfare in the area.

Compared with Iroquois settlements, most Abenaki villages were fairly small, averaging about 100 persons, but there were exceptions – particularly among the Western Abenaki. Some Abenaki used an oval-shaped long house, but most favored the dome-shaped, bark-covered wigwam during the warmer months. During winter, the Abenaki moved farther inland and separated into small groups of conical, bark-covered wigwams shaped like the buffalo-hide tepee of the plains.

Abenaki Couple

18th-century watercolor by an unknown artist

The Abenaki were noteworthy for their general lack of central authority. Even at the tribal level, the authority of their sachems was limited, and important decisions, such as war and peace, usually required a meeting of all adults. The Abenaki Confederacy did not come into existence until after 1670, and then only in response to continuous wars with the Iroquois and English colonists.

In many ways the lack of central authority served the Abenaki well. In times of war, the Abenaki could abandon their villages, separate into small bands, and regroup in a distant refuge beyond the reach of their enemies. It was a strategy that confounded repeated efforts by both the Iroquois and English to conquer them. The Abenaki could just melt away, regroup, and then counterattack.

European Contact

In the early 1500s, European fishermen were fishing for cod, haddock, and other fish found in the Grand Banks. The Grand Banks are a series of raised submarine plateaus found off the southeast coast of Newfoundland, and are one of the richest areas in the ocean for fish. The European fishermen who fished off the coast of Canada and northern New England eventually came ashore and began to trade with the Abenaki.

For the Abenaki, the new coastal trade meant it was easier to get better tools. They no longer had to trade with their old enemies, the Iroquois, for the “good stone from the west.” The European newcomers had better ax heads and wonderful metal pots and blankets, which were almost as warm as a woven rabbit skin blanket and far less work to get. Tanning skins was very hard work, and the newcomers would often trade a whole blanket for a single beaver skin.

The culture of the New Hampshire tribes was similar to that of their relatives in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Long Island.

By the mid-1600s, the Native American population in New Hampshire was declining. They had no natural immunities against diseases such as smallpox and influenza that were introduced by European settlers, and major epidemics broke out between 1615-1620 that decimated populations.

Conflicts with invading Mohawks and tensions with European settlers claiming ownership of Abenaki ancestral lands made the situation even worse. By the 1690s, many of the remaining Abenaki had either married Europeans, melted into the rural population, or settled in Canada.

For the most part, the Abenaki had remained neutral in the struggles between Britain and France, but the alliance between the English and Iroquois pushed them to the French. The Abenaki not only resented English support of the Iroquois but were increasingly concerned about the appetite of the New England colonists for land.

The Pennacook

Living along the Merrimack River of southern New Hampshire and northeastern Massachusetts, the Pennacook were the southernmost Abenaki group and the first to have extensive contact with the English. Decimated by the recent epidemics, they were also threatened from the west by the Mohawk and distrusted the intentions of the Abenaki in Maine. The Pennacook extended well-inland along the Merrimack River to a point where their boundaries with the Sokoki (the Western Abenaki) blurred.

The Sokoki and Pocumtuc (Connecticut River in western Massachusetts) had a long history of hostility with the Iroquois, and helped the Mahican in their war against the Mohawk (1624-28), with the Pennacook being drawn in as allies of the Sokoki. The Mohawk eventually won, forced the Mahican east of the Hudson, and began to attack the Sokoki and Pennacook.

The Pennacook welcomed and made an alliance with the English settlements in Massachusetts. The alliance between the Pennacook and English made the Abenaki uneasy, but the colonists were also concerned about their own safety after the near destruction of Jamestown (Virginia) by the Powhatan in 1622.

The Legacy

The Native Americans of this region loved the land and were close observers of nature. They gave names to the mountains, rivers, streams, and other natural features and for the most part early European settlers kept them. Today, many places we love in New Hampshire bear the names first given to them by Native Americans.

The native Americans of the northeast all spoke related dialects of a language known as Algonquian. Today, there are less than a 1,000 Abenaki in New Hampshire, and only a few who speak the language.

SOURCES

Abenaki

Abenaki History

People of the Dawn

I would Lillie to contact Abanaki rep in Penacook NH.

My phone # is 804.548.3694