Rhode Island Slaves

Image: Narragansett Planters

Painting by Ernest Hamlin Baker, 1939

A grist mill and sacks of corn being towed by oxen – most of the harvested grain was likely kept in the Colony for consumption by the planters and their livestock.

Rhode Island established the first law regulating slavery on May 18, 1652, as part of the Acts and Orders of the General Court of Warwick. It stated that the blacks or whites forced to serve another must be freed after 10 years after arrival in Rhode Island. The fine for noncompliance was 40 pounds. The law was evidently never enforced, because African slaves were in the Colony that same year. The demand for cheap labor had prevailed.

Between 1709 and 1807, Rhode Island merchants sponsored at least 934 slaving voyages to the coast of Africa and carried an estimated 106,544 slaves to the New World. By the end of the 17th century Rhode Island had become the only New England colony to use slaves for both labor and trade.

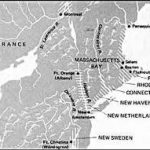

The Triangle Trade

During the colonial period, Rhode Island was one corner of what has been named the Triangle Trade, by which slave-produced sugar and molasses from the Caribbean were carried to Rhode Island and made into rum. The rum was then shipped to West Africa in barrels and exchanged for slaves, in order to produce more sugar, more rum, and more slaves. From 1732 to 1764, each year the Colony sent 18 ships bearing 1,800 hogsheads of rum to Africa to trade for slaves. Rum fueled the slave trade.

Several Rhode Island merchants not only distilled and sold rum, but also controlled large sugar plantations—men like Abraham Redwood, who inherited from his father a large sugar plantation in Antigua that was manned by over 200 slaves. Redwood used the profits from his plantation and slave trading business to establish Redwood Library in Newport, America’s oldest existing library. The Quaker Church in Newport asked Redwood to either leave the African trade or leave the church. He left the church.

The towns of Newport and Bristol became the major slave markets in the American colonies. Newport’s economic success from African slave labor in making rum was best described by 19th century American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson when he stated, “The sugar they raised was excellent; nobody tasted blood in it.”

The Slave Population

Little Rhode Island generally had a smaller population of black slaves than its neighbors, Massachusetts and Connecticut, but with a very small white population as well, Rhode Island’s blacks made up a higher percentage of the total population than elsewhere in New England. As early as 1708, slaves outnumbered white indentured servants in the colony almost 8 to 1.

The biggest increase in black population came in the years from 1715 to 1755, which coincided with the industrial development of the colony and its emergence into the slave trade. Commercial success bred a wealthy class that became a slave-owning aristocracy.

Rhode Island’s black population tripled from 1715 to 1730, and almost tripled again by 1755. Slave-based economies grew in the Narragansett plantations, the Middletown crop workers, and the indentured and slave craftsmen of Newport. By 1730, the southern part of Rhode Island was one-third black, nearly all of them slaves.

By 1774, Rhode Island’s 3,761 blacks were the third highest total in New England. The white population had grown since mid-century, but the colony’s slaves still made up 6.3% percent of the total population, almost twice as high as any other New England colony. The state had the highest proportion of slave-to-white of any colony in the North, which tended to make slave laws more severe.

Slave Laws

Rhode Island’s slave laws were the harshest in New England. The runaway law of 1714 penalized ferrymen who carried slaves out of the colony without authorization from their masters. The law against thefts by slaves carried a sentence that could be 15 lashes or banishment from the colony—a particularly dreaded punishment, because it usually meant deportation and sale to the merciless sugar plantations in the West Indies.

The town of South Kingstown had perhaps the harshest local slave control laws in New England. After 1718, if any black slave was caught in the cottage of a free black person, both were whipped. After 1750, anyone who sold so much as a cup of hard cider to a black slave faced a harsh fine of 30 pounds.

The Narragansett Planters

While Newport merchants profited by trafficking in slaves, colonists across the bay found another way to get rich. In Narragansett County, conditions favored large-scale farming, and a system began to emerge that looked like the Southern plantations. There, amid the rolling hills and fertile fields, hundreds of enslaved Africans worked for a group of wealthy farmers in South Kingstown, North Kingstown, Narragansett, Westerly, Exeter, and Charlestown.

Narragansett planters used their slaves both as laborers and domestic servants. They cut wheat, picked peas, milked cows, husked corn, cleaned homes and built the waist-high walls that bisected the fields and hemmed them in. They raised livestock and produced surplus crops and cheese for Newport’s growing sea trade.

By 1730, the most successful planters owned thousands of acres. William Robinson owned an estate that was more than four miles long and two miles wide, and he kept about 40 slaves there. The Stantons, who were among the province’s leading landowners, owned a 5,760-acre estate that stretched more than four miles long, and had at least 40 slaves. Robert Hazard of South Kingstown owned 12,000 acres and had 24 slave women just to work in his dairy.

The prosperous Narragansett Planters provided the food and livestock that were so vital to the huge sugar cane plantations in the West Indies. For 50 years, Newport’s merchants loaded the surplus farm products onto ships bound for slave plantations in the islands, and traded them for sugar and molasses. Made rich from their exports, the planters built big homes, sent their children to private schools and carved the hillsides into apple orchards and gardens. Their large houses often stood more than a mile apart.

Rhode Island remained the leading slave trader of the colonies until a partial ban was placed on importation of slaves in 1774. On June 13, 1774, an act for the Non-Importation of Slaves was passed by the Rhode Island General Assembly. It stated:

No Negro or mulatto slave shall be brought in to this colony, and in case any slave shall be brought in, he or she shall be…immediately free, so far as respects personal freedom, and the enjoyment of private property.

Gradual Emancipation

In 1783, Moses Brown and other Quakers began to petition for the abolition of slavery in Rhode Island. After a difficult battle, the General Assembly passed the Gradual Emancipation Act of March 1, 1784. It stated that children born to slaves after that date would be free after reaching the age of 21 for boys and 18 for girls. All slaves born before 1784 would remain slaves for life. In the 1790 federal census, there were still more than 260 slaves in Newport.

This gradual emancipation was due in large part to the performance of slave and free African members of the First Rhode Island Regiment, who had distinguished themselves during the American Revolution. But there was also a larger public demand that challenged the notion that the fight for independence from Great Britain could only be truly righteous when Rhode Island ended its involvement in African slavery. At the height of this debate, the Newport Mercury newspaper offered this compelling editorial statement to its readers:

If Newport had the right to enslave Negroes, then Great Britain has the right to enslave the Colonists.

SOURCES

Slavery in Rhode Island