The 1630s

The Puritans who settled the New England colonies came to America to escape religious persecution in their homeland. Their isolation in the New World, their introversion, the harshness and dangers of their new existence insured that American Puritanism would remain more severe than that which they had left behind.

The Puritans believed that they were the Chosen People of God destined to found a New Jerusalem—a New City of God in the wilderness. They interpreted the Bible more literally than their British counterparts, and sought to establish a purified church, which sometimes meant imposing their religious beliefs on unwilling citizens.

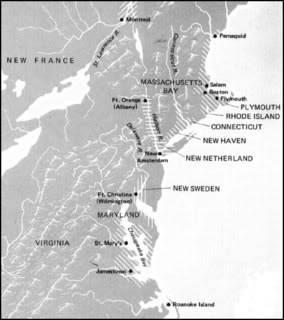

The Colonies

Massachusetts Bay Colony: 1629-30

Unlike the poor and humble Pilgrims, the founders of Massachusetts Bay Colony were men of wealth and social position. They left comfortable homes in England to found a Puritan state in America. They got a great tract of land extending from the Merrimac River to the Charles, and westward across the continent.

Hundreds of colonists came to Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. They settled at Boston, Salem, and other towns nearby. In the next ten years, thousands more joined them. Massachusetts was strong and prosperous from the very beginning.

The Connecticut Colony: 1634

Except for the people the Massachusetts Puritans drove from their colony, there were other settlers who left Massachusetts of their own free will. They were not content with the Puritans and decided to leave. Among these were the founders of Connecticut. They settled the towns of Hartford, Windsor, and Wethersfield on the Connecticut River.

At about the same time, John Winthrop, Jr. led a colony to Saybrook, at the mouth of the Connecticut River. Up to that time, the Dutch seemed to have the best chance to settle the Connecticut Valley, but the control of that region was now definitely in the hands of the English. The Connecticut people had no charter, and they wanted something more definite than a vague compact.

So in the winter of 1638-39 they met at Hartford and set down on paper a complete set of rules for their guidance. The Connecticut constitution of 1638-39 is looked upon as “the first truly political written constitution in history.” The government they established was similar to that of Massachusetts, with one key exception—in Connecticut you didn’t have to be a member of the church to vote.

Rhode Island: 1636

Roger Williams, a Puritan minister, disagreed with the Massachusetts leaders on several points. He thought that the colonists had no right to lands that were not purchased from the Native Americans. And he insisted that the rulers had no power in religious matters.

He insisted on these points so strongly that the Massachusetts government expelled him from the colony. In the spring of 1636, with four companions, he founded the town of Providence. There he decided that every one should be free to worship God as he or she saw fit.

New Haven: 1638

The settlers of New Haven went even farther than the Massachusetts rulers and held that the State should be a part of the Church. So Massachusetts was not entirely to their liking. They passed only one winter there, then moved away and settled New Haven.

The colony’s success soon attracted other believers, as well as those who were not Puritans. They expanded into additional towns: Milford and Guilford in 1639, Stamford in 1640, and later to Fairfield, Medford, Greenwich, and Branford. These towns formally joined together as the New Haven Colony in 1643. They based their government on that of Massachusetts, but they maintained stricter adherence to the Puritan discipline.

The New England Confederation: 1643

When civil war in England broke out in 1641, the New England colonists—more than twenty thousand, with fifty villages, almost forty churches, and currently without any pressure from the motherland—seriously began to contemplate the establishment of a new nation. In 1643, the British Parliament acknowledged that “the plantations in New England had, by the blessing of the Almighty, had good and prosperous success without any public charge to the parent state.”

The New England Confederation was a political and military alliance of the British colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, and New Haven. Established in 1643, its primary purpose was to unite the Puritan colonies against the Native Americans living in their midst, against the French to their north, and the Dutch in the New Netherland Colony to their west.

There were colonists living in Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Maine. Those colonies asked to be admitted to the Confederation, but were denied. Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop said they were refused, “because they ran a different course from us, both in their ministry and civil administration.” Whatever that means.

The business of the confederation was to be transacted by a commission of eight men, two from each colony. A vote of six was required to carry a measure. The expenses as well as the spoils of war were to be divided among the colonies, in proportion to their respective male populations between the ages of sixteen and threescore years. The articles provided for the delivering up of the runaway slaves and of fugitives from justice. This feature was the prototype of the Fugitive Slave Law of a later generation.

The New England colonies were all settled on the town system. There were no industries that demanded large plantations—like the cultivation of tobacco. The colonists were small farmers, mechanics, ship-builders, and fishermen. There were few servants in New England and almost no African slaves. Most of the laborers were free men who worked for wages.

The confederation disintegrated in 1654 after Massachusetts Bay Colony refused to join the war against the Netherlands during the First Anglo-Dutch War.

SOURCES

New England

Founding of Massachusetts

Colonial New England Affairs

History of the New England Colonies